The Adat (customary laws) of the Andi of Daghestan

The following list of the adat of the Andi people of Daghestan was copied from Prof. Mamaikhan Aglarov's The Andi: A Mountain People of the Caucasus (Makhachkala: Iupiter, 2002; originally published in Khristomatia po istorii prava i gosudarstva Daghestana, vv. VIII-XIX, p.82, Makhachkala: 1999).

Although this list of laws is, of course, specifically related to the Andi, one can safely assume that it shares many of its principles and provisions with the customary laws of many of the other peoples of the Caucasus, as well as with those prevalent in Albania (where adat is known as kanun), in Anatolia, &c.

FIRST CHAPTER: MURDER

1.1 For any murder – whether premeditated or accidental, and wherever it may have been committed – the Law states that the murderer has to pay a diyat [fine] of 100 rubles to the relatives of the deceased. [Note: At the time of writing, a sheep seems to have cost 2 rubles; an ox – 10; etc.] Of these, 50 must be paid when the relatives of the murderer visit those of the deceased accompanied by the village dibir [a delegation of respected villagers] and an ox [whose sacrifice is necessary for the reconciliation of the two parties], and 50 following the verdict of the village tribunal. Until the two parties are reconciled, the murderer may not plough his land, make hay, or freely use his property; he has the right to remain in his home or in the village, but the relatives of the deceased have the right to pursue him [to prosecute a blood feud - i.e. to kill or otherwise prosecute him].

1.2. In cases of accidental murder [manslaughter] or the murder of a thief, the murderer is subject to the same laws, and must pay the same diyat.

1.3. Should a husband kill both his wife and her lover, he is not deemed responsible for their deaths. Should he only kill his wife's lover, however, his act is considered as murder.

1.4. The testimony of a dying victim of murder – even if this person points to or accuses a known enemy of his – is accepted as proof of that person's guilt.

1.5. If the relatives of a victim of murder accuse someone of his death, this accusation is accepted as proof without oath.

1.6. A person who confesses to a murder is considered guilty if he confesses on the day of the crime and if he has a permanent abode, "a house and property, the house having at least 7 cross-beams". If two people should confess to a murder, only one of them is considered guilty, at the discretion of the victim's relatives. The confession of a youth is considered equal to that of an adult; the confession of a woman is only accepted as such if it is confirmed by a number of witnesses.

1.7. A person accused of murder by the victim or his relatives becomes their mortal enemy.

1.8. If both murderer and victim fight and die of their wounds, their deaths are considered as "blood for blood", as if they had died natural deaths. If, following a fight, one party is merely wounded and the other unharmed, intermediaries agree upon a masliat [a compromise] and the first 50 rubles [see 1.1] are not to be paid until the matter is cleared up. Even if the wounded party recovers, and lives, the other is accused of his murder.

1.9. A father cannot be held responsible for the murder of his own son. Should a man kill his own brother, he must leave the village and live as an outlaw [as a kanly or, more commonly, as an abrek], according to the wishes of his brother's children.

1.10. Should a son kill his own father [parricide], he is deprived of his inheritance, and must leave the village and live as an outlaw. He is deemed responsible for his father's blood before his paternal uncles.

1.11. Should a man kill his konak [his honorary kinsman and host from another village, tribe, or people], he must pay his konak's house's new host and master 100 rubles, and his konak's relatives become his mortal enemies. If the identity of the murderer is unknown, the relatives of the deceased may accuse anyone without swearing an oath, and this person will become their mortal enemy.

1.12. Should a husband kill his wife, or a wife kill her husband, the one who remains becomes the mortal enemy of the relatives of the deceased.

1.13. Should any person harbour, protect, or hide a murderer in his home, this person becomes a mortal enemy of the relatives of the deceased.

1.14. Should a child kill or wound anyone, it will be tried as an adult.

1.15. Should any animal – whose bad character was known to its owner, and if the latter did nothing to restrain it – kill anyone, the animal's owner must answer for the murder as if he had done it himself.

SECOND CHAPTER: INJURY

2.1. Should a person wound another in a fight, and no one has confessed or otherwise claimed responsibility, the person the victim will accuse will be considered responsible for the crime.

2.2. If no one confesses and the victim accuses a person of the crime, the victim may not [at a later stage] point to anyone else but this first person.

2.3. A person wounded in several places may only accuse one person of the crime, and this person is deemed solely responsible.

2.4. Should a person be wounded during an argument, or wounded by accident, the guilty party answers for the crime as for wounding in general. However, if the victim was deliberately wounded, the guilty party must also present the victim's family with an ox [see 1.1]. If a thief is wounded, the guilty party must answer as for wounding in general, but the thief's relatives must present the latter with an ox.

2.5. Money may be substituted for oxen.

2.6. Doctors treat the wounded at the guilty party's expense. Should the village of the wounded person be too remote for a doctor to be called for, the wounded may choose a substitute for the doctor, who will treat him at the guilty party's expense.

2.7. For severing or disabling an arm, hand, or foot, the guilty party must pay 150 rubles; for severing or disabling a finger, the guilty party must pay a fine which decreases from 50 rubles for a thumb down to 10 rubles for a little finger.

2.8. For inflicting a wound above the elbow, as the result of which the victim can no longer move the elbow-joint, the guilty party must pay 50 rubles.

2.9. For disabling his victim's leg, the guilty party must pay 150 rubles.

2.10. For severing a toe, the guilty party must pay a fine which decreases from 10 rubles for a big toe down to 6 rubles for a little toe.

2.11. For injuring his victim's tongue, as a result of which the latter can no longer speak or has difficulty speaking, the guilty party must pay 50 rubles.

2.12. For disfiguring his victim's nose, the guilty party must pay 150 rubles.

2.13. For inflicting injury to his victim's penis or otherwise depriving the latter of the ability to have sexual intercourse, the guilty party must pay 100 rubles.

2.14. For knocking out his victim's teeth, the guilty party must pay at least 10 rubles per tooth.

2.15. For blinding his victim's eyes, the guilty party must pay 100 rubles for one eye, and 400 rubles for both eyes.

2.16. For depriving his victim of hearing, and if real deafness is established, the guilty party must pay 50 rubles for one ear, and 100 for both ears. If, over time, the victim recovers his hearing, the money is returned.

2.17. For severing even a third of one of his victim's ears, the guilty party must pay 35 rubles, as he would for any wound to the face.

2.18. The guilty party must provide his victim with food, and with anything the doctor deems necessary for the victim's treatment. A close relative of the guilty party must accompany the doctor and carry the doctor's bag, and must remain present during the entire treatment. Following treatment, when the victim has recovered, the guilty party must bring him a sheep or 2 rubles and three measures of flour, and must invite the victim and twelve other guests to a feast and thus reconcile the two parties.

2.19. Should any person be wounded to the head and suffer broken bones, in addition to the required penalty the guilty party must pay the victim 10 rubles on the day of reconciliation.

2.20. Should a person's inner organs be wounded, the injury must be established by a doctor in the presence of two or three witnesses and judges.

THIRD CHAPTER: ADULTERY

3.1. Any woman or girl who has been attacked by a man intent upon raping her must shout at once and inform every person she meets of the fact, most particularly her husband and their relatives. If she does so, her statement is accepted without her having to swear an oath; should she omit this rule, and delay her declaration until the following day, then her statement will not be considered valid.

3.2. If the offended woman or girl declares and proves her statement, the accused must marry her and pay 40 rubles to her closest relatives. However, if the woman's relatives disagree with her marrying the accused, the latter must not answer for anything.

3.3. The offended woman or girl may stay with her relatives, but she must inform the authorities, and may not stay with her relatives for more than half a day.

3.4. For insulting his divorced wife, a man answers as for insulting any other woman. Should the offended woman wish to marry him, she must first marry another, and then marry him. Should she not wish to marry him, the man answers for nothing. [The two latter sentences are unclear.]

3.5. Insulting a girl engaged to be married is considered equivalent to insulting a married woman.

3.6. If a woman or girl has extramarital relations with a man of her own free will, the woman or girl is held responsible, and the man is not fined.

3.7. Any one, who has cut off a woman's plait of hair, must pay her 15 rubles for each plait, in addition to the penalty called for insulting her.

3.8. Those deemed to have been accomplices in the kidnapping of a girl, a widow, or any other woman are fined 10 rubles each, and the same sum must be paid by the owner of the house who received the fugitives, but only if the latter was at home.

3.9. If a woman or girl did not declare a case of adultery and later becomes pregnant and accuses the man responsible, her declaration is not considered valid, but the man she accused must clear himself of the charge by an oath of twelve character witnesses, as for a theft; if he doesn't, he must marry the woman or girl after the child is born, and recognize the child as his.

3.10. If, during the insulting or kidnapping of a woman or girl, a man is wounded by her relatives, the latter cannot be held responsible, but the insult or kidnapping must be proved by witnesses. If the man was wounded after having insulted or kidnapped a woman or girl, or if he was wounded whilst under the protection of any house, the guilty party must answer as for any other instance of injury.

3.11. If a woman having concealed a case of adultery later becomes pregnant and gives birth, she is fined as well as the man for the adultery.

FOURTH CHAPTER: ENGAGEMENT

4.1. If two people were engaged in the presence or with the agreement of the village court, and the girl or her relatives later refuse to marry her to the man she was engaged to, the girl's parents must return all the gifts presented and repay all the expenses incurred by her fiancé, and pay an additional fine of 50 rubles.

4.2. Should there be an argument concerning expenses, the fiancé must declare the amount by swearing an oath with character witnesses; if this is not done, the father of the girl or the girl herself must declare the value of the gifts she received at the engagement ceremony by swearing an oath with witnesses, and this sum will be exacted as expenses.

FIFTH CHAPTER: THEFT

5.1. The victim of theft must declare the theft by swearing an oath along with one of his closest relatives not involved in the matter.

5.2. If a stolen animal is later found, its value before and after its theft is established; its value before its theft is declared by its owner under oath, and its value after its theft is established by the court or by people appointed by the court; should the owner of the stolen animal not be satisfied with the value, he may demand compensation equivalent to the expense of searching for the animal; this compensation will be exacted from the thief, but only if he has been proven to be guilty.

5.3. If something has been stolen from a house, the guilty party must pay the victim at last 10 rubles or present the victim with an ox [see 1.1.] in addition to the fine called for by law.

5.4. If something has been stolen from a house, the accused must clear himself by swearing an oath along with twelve character witnesses.

5.5. For any theft outside a house, the number of character witnesses required to swear an oath in support of the accused are as follows: For a horse – 6 people; for a cow – 5 people; for every sheep – 2 people; and for any other property the village court will appoint the number of witnesses required according to the value of the things stolen.

5.6. Character witnesses are appointed by the victim, but may not include close relatives of his such as a brother, a son, a cousin, a brother-in-law, a father-in-law, or those who are mortal enemies of the accused.

5.7. If something was stolen from a guest, the latter and his host must obtain satisfaction.

5.8. On the day of his lodging a complaint, the victim of theft has the right to accuse seven suspects of the crime, but following this he no longer has the right to accuse anyone else.

5.9. If a victim of theft declared the theft in court and later finds some of the stolen things in somebody's house, the victim has the right to demand the restitution of the remaining stolen things from this person. If a thief who has confessed to a crime names his accomplices, the victim has the right to accuse them, too.

5.10. If a thief has not the means with which to compensate his victim, then compensation will be exacted from the person the thief lives with, regardless of this person being a relation of his or not.

5.11. If a shepherd, a servant, or a guest is known to be a thief, and if the village authorities have informed the host of this fact, and if – despite having been warned – the host does not turn him out of his house and allows him to remain there for at least three more days, then any theft the aforementioned person may commit will be deemed to be his host's responsibility.

5.12. A declaration of theft is no longer deemed valid, if after one year none of the stolen things have been found among the possessions of the accused.

5.13. People previously condemned for theft or bribe-taking cannot be chosen as character witnesses for clearing a suspect of theft.

5.14. If stolen items are found in a person's house, then this person is found guilty and fined accordingly, even if this person was not accused by the victim in the first place.

5.15. Any theft committed by children under age (younger than 10) is not regarded as a crime.

5.16. Women are allowed to clear themselves of an accusation by the swearing of an oath by other women. It is deemed impossible to establish the rightful owner of the following goods: wool; bourkas [felt cloaks] (except those which have been worn); cloth; meat; iron; and money. The property of clothes, animals, animal skins, etc. can be identified.

5.17. Counter-accusations of theft may not be brought sooner than in a year's time from the date of the original accusation.

5.18. Killing cattle is considered as theft.

SIXTH CHAPTER: CONCERNING THE DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF SHEPHERDS AND HORSE-HERDS

6.1. A shepherd must always be near his flock and do his best to watch over them and to ensure that they are not stolen by wild animals or thieves. If a wolf injures or steals a sheep in the presence of the shepherd, then the latter must bring the owner some part of the injured or stolen sheep – the head or ear, etc. – otherwise the owner can declare under oath that the injury or theft of the sheep was the shepherd's fault or for his benefit, or he can demand that the shepherd swear under oath that he was not to blame and end the matter there and then.

6.2. The village is responsible for the safety of the shepherds and horse-herds it hires. Everyone may bring his animals to the herd himself or under the care of someone else, even of a child. If animals on their way to the herd should be stolen, and the herder declared that he never received the animals in question, then the owner can exact from the party found guilty a fine equivalent to that exacted for the crime of not returning the amanat [any sort of property given to someone for safe-keeping]. Should the herder confess that he did receive the animals, but declare that he was not to blame for their being stolen, he must nonetheless pay the owner half of the value of the stolen animals.

6.3. Should shepherds or horse-herds allow their herd to pasture on land which has been declared prohibited for pasturing and animals fall down a steep slope or into a deep ravine, if the herders do not slaughter the latter [to bring back the valuable meat], then the value of the lost animals is exacted from the herders, value which is fixed in court according to the declaration under oath of neighbours who knew the cattle.

6.4. Should animals be driven to pasture on land which has been declared prohibited for pasturing and animals fall down a steep slope or into a deep ravine, if the herder was able to climb down and slaughter the latter, but didn't, he must compensate the owner for the loss of the meat; if he did, he may go free. He may also go free if the slope was so steep that he could not reach the lost animals.

6.5. Herders must inform the owner of an animal being ill. If the illness worsens and the owner does not come, the herder has the right to slaughter the animal.

SEVENTH CHAPTER: CONCERNING THE KILLING OF DOGS

7.1. For killing a dog within the bounds of someone's mulke [the territory of someone's house] or in someone's field, the guilty party must pay the owner 5 rubles. If a dog tears someone's clothes, the dog's owner must compensate the victim.

7.2. For cutting off a dog's ear or the ear of any other animal, the guilty party must pay the owner the price of the animal as fixed by witnesses, or give him a similar animal. The guilty party may keep the injured animal, at the discretion of the court.

7.3. For injuring a dog, if the dog does not die, the guilty party may go free.

EIGHTH CHAPTER: CONCERNING THE CUTTING DOWN OF TREES

If someone has cut down a tree without permission, this is considered as theft; the guilty party will be fined, and must return the wood to the owner.

NINTH CHAPTER: CONCERNING PROPERTY SHARED BY A COUPLE

If a husband and wife have an argument concerning property which they bought together when they got married, the case is investigated according to shariat [Islamic law].

TENTH CHAPTER: CONCERNING DAMAGE CAUSED TO A FIELD

The victim whose field was damaged must make a declaration to the village court. The court will send two people to investigate, and if they confirm the damage claimed, the owner of the damaged field will be compensated.

ELEVENTH CHAPTER: ARSON

11.1. If something is damaged or destroyed by fire within the bounds of someone's mulke [see 7.1], the suspect must be cleared of the accusation by twelve character witnesses under oath. However, if the owner of the burnt property is known to be a dishonest man or a thief, and if he accuses a person known to be honest, three of his relatives must prove that the arson was not committed by the owner himself.

11.2. If something is damaged or destroyed by fire without the bounds of someone's mulke, in another place, the suspect must be cleared of the accusation by six character witnesses under oath. If in the first or the second case [11.1 or 11.2] the suspect is not able to clear himself of the accusation, he must compensate the owner for the damage caused.

11.3. If it is established that arson within the bounds of someone's mulke was committed by several people, then each must present the victim with an ox [see 1.1] in addition to compensation for the burnt property.

Falling foul of adat: revenge for article 1.7.

|

|

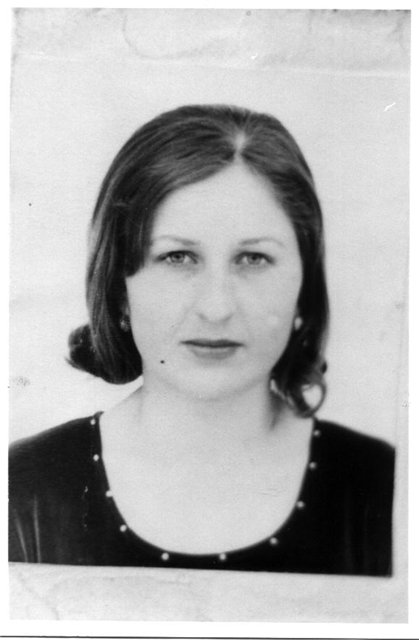

On Friday 10 June 2011, former Russian colonel Yuri Budanov—accused of raping and torturing 18 year-old Elza Kungayeva and convicted of kidnapping and strangling her while serving in Chechnya in 2000, imprisoned for 10 years in 2003 and released early in 2009, the only senior Russian officer to be jailed for crimes committed in Chechnya—was shot by an unknown gunman on a busy Moscow avenue. |

|---|

BBC News: 10 June 2011

Russian colonel who killed Chechen girl is shot dead

A Russian colonel who was jailed for murdering a Chechen teenager has been shot dead in central Moscow.

Yuri Budanov was killed on Friday by an unidentified gunman on Komsomolsky Prospekt, a busy avenue in the capital, state prosecutors said.

In 2003 a court upheld his 10-year jail sentence for strangling an 18-year-old girl in war-torn Chechnya in 2000. But he was released early from jail in January 2009 - a move that angered human rights activists.

Russian media say the gunman, wearing a blue jacket and hood, attacked Budanov at about 1230 (0930 GMT), shooting him six times with a pistol, then fled by car.

The Mitsubishi Lancer getaway car was later found abandoned and on fire, the reports said. A pistol and silencer were found inside.

The Budanov trial was big news in Russia, where very few officers have been prosecuted over abuses committed during Russia's two campaigns against Chechen separatist rebels.

He was the only senior officer to be jailed for crimes committed in Chechnya.

He was found guilty of the kidnapping and strangling of Elza Kungayeva in 2000. An allegation that he had also raped her was dropped.

The murder provoked outrage in Chechnya, where many civilians have died at the hands of Russian forces and the local pro-Moscow militia, during the long war against rebels.

At his re-trial in 2003 Budanov accused Russian media of having swayed the judge, insisting that he was "a Russian soldier who defended his country for the past 20 years".

Budanov was acquitted at his first trial in December 2002, when the court accepted his plea that he had been temporarily insane at the time of the killing.

But the Russian supreme court ordered a re-trial, where he was found to have been of sound mind at the time. He was found guilty and stripped of his rank and the Order of Courage, which he had won in breakaway Chechnya.

Budanov told the court he believed that Kungayeva was a Chechen sniper and that a fit of rage had come over him as he interrogated her.

The lawyer representing Kungayeva's family, Stanislav Markelov, was shot dead in Moscow in January 2009, along with a journalist, Anastasia Baburova, who was with him at the time.

Stanislav Markelov

Last month a court in Moscow sentenced a Russian nationalist to life imprisonment for the double murder. His partner was also jailed.

RFE/RL: May 07, 2013

Chechen Sentenced For Murder Of Russian Army Colonel Budanov

Yusup Temerkhanov (right), an ethnic Chechen, is seen in the dock in a Moscow city courtroom in November.

After five months of court proceedings that Chechnya’s human rights ombudsman, Nurdi Nukhadzhiyev, dubbed a "witch hunt" and a travesty of justice, a Moscow court has found the ethnic Chechen Yusup Temerkhanov guilty of the murder of former Russian Army Colonel Yury Budanov -- even though two eyewitnesses say Temerkhanov was not the killer and he had no obvious motive.

The presiding judge then sentenced Temerkhanov on May 7 to 15 years in prison. The prosecution had asked for a 16-year sentence.

Investigators established that Budanov was shot dead on a busy Moscow street on June 10, 2011 by a lone gunman who escaped in a silver Mitsubishi Lancer with false papers and license plates that was later found abandoned. Budanov had gained notoriety during the 1999-2000 Chechen war for the cold-blooded rape and murder of Elza Kungayeva, a young Chechen woman he claimed he believed was a sniper. He went on trial for that killing in 2002 but was acquitted.

Following a repeat trial, Budanov was sentenced in July 2003 to 10 years in prison but released on parole in early 2009 after serving only half his sentence and seeing the charges against him annulled. Those rulings triggered a storm of protest in Chechnya. Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov pronounced Budanov an enemy of the Chechen people and argued that his sentence should have been harsher, while human rights ombudsman Nukhadzhiyev wrote to Investigative Committee head Aleksandr Bastrykin denouncing as without legal foundation the decision to annul the charges against Budanov.

Meanwhile, Stanislav Markelov, a lawyer who appealed Budanov’s release on behalf of Kungayeva’s family, was shot dead in Moscow in January 2009.

The circumstances of Temerkhanov’s arrest are disputed. The authorities say he was arrested on August 26, 2011. Temerkhanov, however, claimed in a seven-page written deposition that he was abducted in Moscow one week earlier by masked men who claimed to work for military intelligence and who said they had information that he had been asked to kill Budanov by then-Chechen First Deputy Prime Minister Magomed Daudov. Temerkhanov said the men also asked him if he knew whether Chechen Republic head Kadyrov was involved in Budanov’s murder.

Temerkhanov claimed that when he denied any personal acquaintance with the two top Chechen officials he was subjected to torture. His abductors drove him back to Moscow a week later and left him handcuffed to a tree in a park. He was formally arrested shortly afterward.

The murder investigation lasted almost a year. It established that Budanov had been under scrutiny in the days before his death and that his car had been shadowed by a silver Mitsubishi Lancer in which, according to eyewitnesses, the man who shot him escaped. An identical car was later found abandoned, an attempt to set fire to it, possibly in order to destroy evidence, having failed.

In the car, police reportedly found the gun the killer had used together with a pair of gloves and sunglasses with traces of Temerkhanov’s DNA and a magazine with his partial palm print on it. They also are said to have found groceries and a copy of the daily "Kommersant." A witness for the prosecution identified Temerkhanov as the man who purchased them just hours before the murder.

That latter witness was one of three whose identities were never made public and on whose testimony the formal indictment was largely based. Requests by Temerkhanov’s Chechen lawyer, Murad Musayev, for copies of the protocols of the questioning of those witnesses were refused.

Defense Evidence Rejected

Two unidentified eyewitnesses identified Temerkhanov in court as the killer; his former wife identified him as the man seen on closed-circuit television three days prior to the murder purchasing a blue sweatshirt emblazoned "Fire and Ice" identical to the one the eyewitnesses for the prosecution said the killer wore. A similar sweatshirt was found during a search of Temerkhanov’s Moscow apartment in August 2011. Temerkhanov denied it was his, and his lawyer claimed it had been planted there.

Two other eyewitnesses, however, testified that the killer was shorter than Temerkhanov and had auburn hair. Temerkhanov’s hair is black. According to Temerkhanov’s lawyers, both those men were apprehended by security personnel in February and threatened in an attempt to coerce them to retract their testimony; one was ordered to say Musayev offered him 15,000 rubles ($482) to exonerate Temerkhanov. Chechen human rights ombudsman Nukhadzhiyev publicly deplored those "repressive measures" against witnesses for the defense.

In mid-February, two members of the jury excused themselves from further service, whereupon the presiding judge dissolved the jury, selected 12 new jurors, and began the proceedings again from scratch. Musayev unsuccessfully protested that decision.

Temerkhanov said in court that he was not in Moscow on the day of Budanov’s murder but out of town undergoing treatment with a chiropractor for his back. The therapist in question testified that he had indeed treated Temerkhanov on the day of the murder. The prosecution, however, produced evidence that Temerkhanov visited a Moscow fitness club on June 10.

A further item of circumstantial evidence was that Dzhamal Paragulgov, an Ingush acquaintance of Temerkhanov’s, asked one of his contacts, who testified for the prosecution, for help in securing false papers and registration plates for a stolen Mitsubishi Lancer identical to the one in which the killer made his escape.

But Aleksandr Yevtukhov, one of the two eyewitnesses who said the murderer was definitely not Temerkhanov but a shorter man, also said that the Mitsubishi Lancer in which the murderer fled the scene was not the car later found abandoned.

Defense lawyer Musayev has outlined the possibility that "Dzhamal" was the real killer but that by the time investigators realized that, Dzhamal had already left Russia, and so they decided to make Temerkhanov the scapegoat. What motive Dzhamal may have had, or whether he was hired to carry out the killing and if so by whom, is unclear.

Investigators inferred that Temerkhanov’s motive for shooting Budanov was hatred of the Russian military en masse, given that drunken Russian troops arbitrarily killed Temerkhanov’s father in February 2000 in his native village of Geldagen. Temerkhanov’s paternal uncle, however, testified in court that Temerkhanov did not feel any enmity toward the Russian armed forces for that killing.

Indeed, if Temerkhanov had, as the prosecution argued, conceived in the early 2000s the plan of killing at random a symbolic Russian serviceman to avenge his father’s death, why should he have waited eight years to do so?

The prosecution construed Temerkhanov’s decision legally to change his name to Magomed Suleimanov as part of his imputed extensive preparations for the murder. (That was the name by which he was initially identified at the time of his arrest.) Temerkhanov explained in court, however, that he did so in order to make it impossible for a senior Chechen official with whom he was embroiled in a personal conflict to track him down.

For the same reason, Temerkhanov said, in early 2004 -- when Budanov was still serving the first year of his 10-year sentence for Kungayeva’s murder -- he concluded a fictitious marriage to a Russian woman in order to secure a residence permit for the capital.

The jury rejected the imputed murder motive of revenge, whereupon the prosecution formally asked the judge to alter the first charge against Temerkhanov from "revenge killing" to "murder." Musayev adduced the formal absence of a proven motive as grounds for demanding a retrial. He also said he planned to appeal.

Three of the 12 jury members also found Temerkhanov not guilty.

The 15 years in prison that Temerkhanov received at his sentencing is considerably longer than the term handed down to Budanov for killing Kungayeva.

Retrieved from www.rferl.org on 09/05/2013.

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2015

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb