A JOURNEY IN SOVIET TRANSCAUCASIA

David Roden Buxton's account of his

journey through Georgia and Armenia in 1932

|

|

|

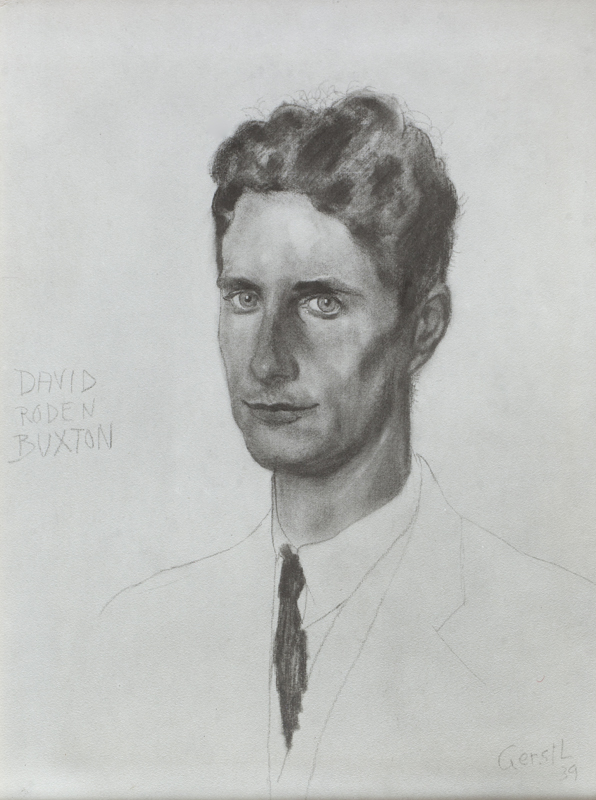

David Roden Buxton (1910-2003) first visited Russia in 1927 with his parents Charles and Dorothy, who were both interested in the communist experiment in Russia and wrote books on the subject. David, already interested in architectural history, was fascinated by Russian architecture. Finding that there were no books on the subject in English, he resolved, at the age of 17, to write one himself. He undertook two long and arduous journeys in the Soviet Union to study and photograph specific buildings (mainly churches) in 1928 and 1932, respectively before and after studying his other great passion—natural sciences—at Cambridge University.

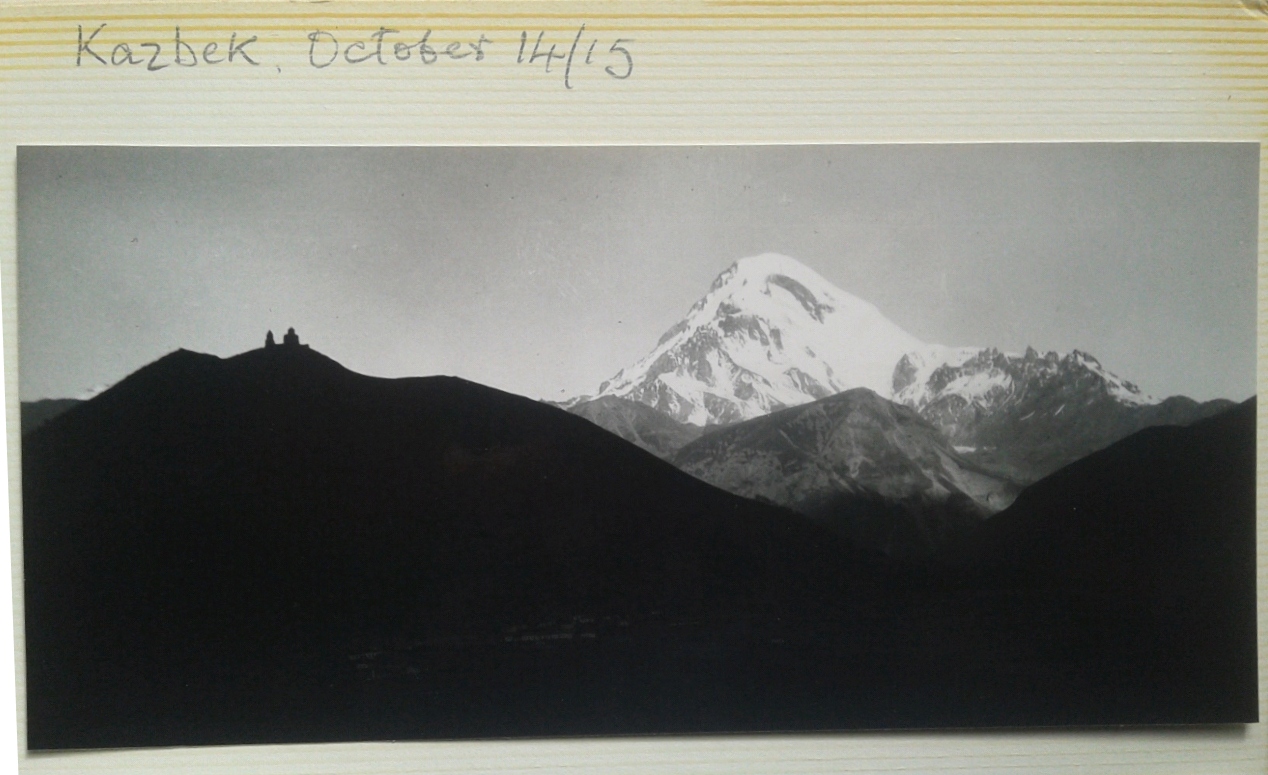

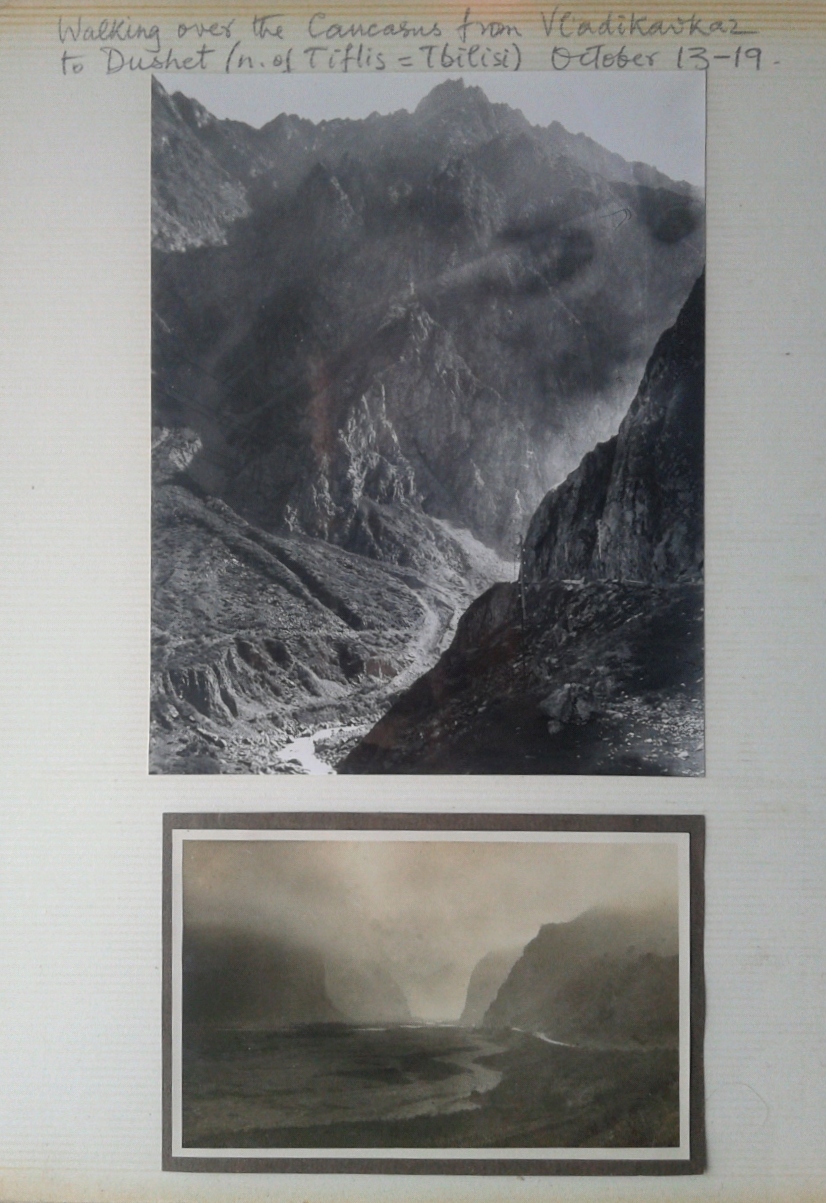

His visit to the Caucasus in the autumn of 1932 was inspired not only by his research interests but also by his love of mountains. His book, Russian Medieval Architecture—with An Account of the Transcaucasian Styles and Their Influence in the West was published in 1934 (Cambridge University Press, 104pp with 108 plates), by which time he was working on locust control in Kenya. He subsequently lived in Ethiopia and wrote books about the country and its ancient Christian heritage. Later in life he returned to his earlier interests, and his book The Wooden Churches of Eastern Europe was published in 1981.

A map showing Buxton's 1932 itinerary through Soviet Transcaucasia.

(The circles indicate architecture that was of particular interest to him.)

|

|

|

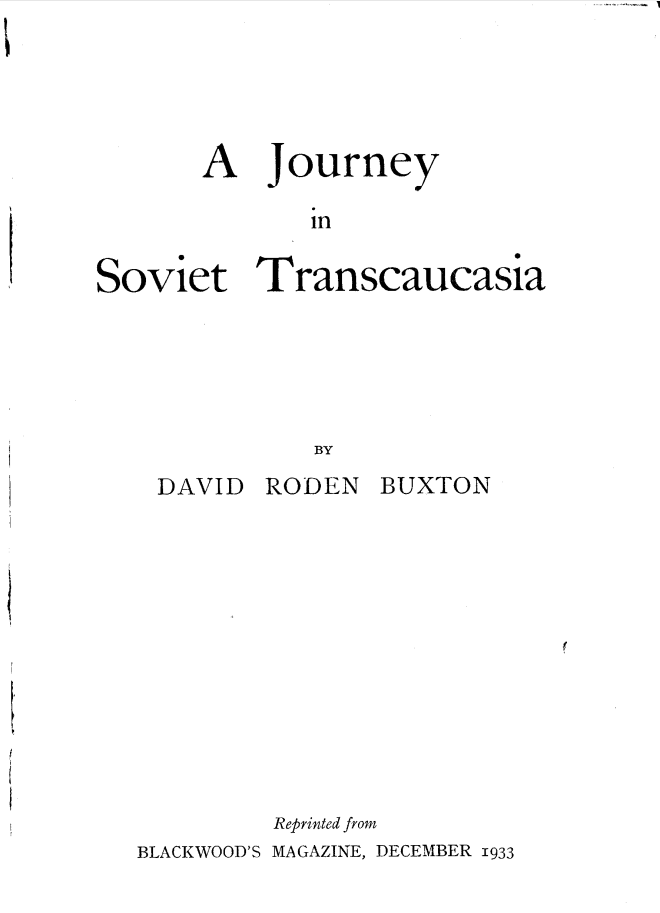

The full text (in pdf format) of his account of this journey to Georgia is available here. This is a photocopy of its first publication in Blackwood's Magazine, no. MCCCCXVIII, December 1933, vol. CCXXXIV, pp. 767-795. I do of course encourage you to read the whole thing, but in the meantime here is a short passage that I found particularly interesting:

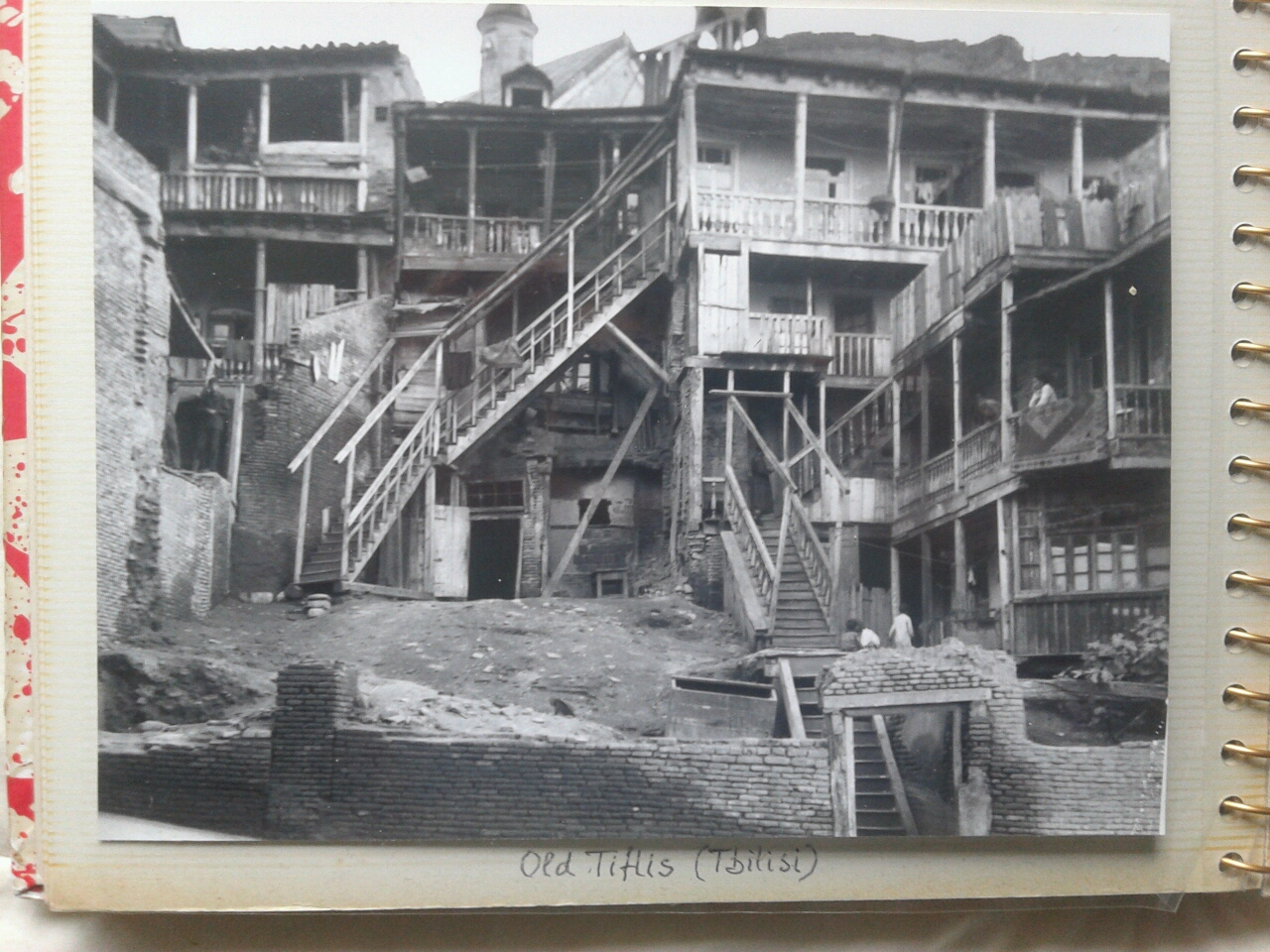

About mid-day I came down to Dushet. I had decided already to walk no farther if I could help it. I had come about a hundred miles, and my appetite for walking was satiated. I was down again at the same level as Vladikavkaz, and felt that the Caucasus was properly crossed. The last thirty miles to Tiflis I knew to be flat and monotonous. It was therefore a great good fortune to find a motor-bus about to start for Tiflis with hardly a passenger on board ; for it was going for some special reason, and nobody knew of it. In the overcrowded buses of the regular line I might never have found a place.

The coach was an old French one [my emphasis] in terribly battered condition, but still doing good service. At the wheel was a desperate and mischievous driver, who pounded at full speed over the roughest parts of the road, as if determined to shatter the vehicle—not without success, for we suffered a burst tyre and several breakdowns, involving protracted delays. Moreover, our driver delighted to strike terror into passing peasants by swerving towards them and missing them by inches; and he seized tomatoes from carts on the road, to fling them back at the carters, amid the loud mirth of the few passengers. At intervals he stopped and took some stimulant, to help him over the next stage. […] Just as darkness was falling, the crashing vehicle drew up before a garage in the outskirts of Tiflis, the great capital city of Georgia and all Transcaucasia.

Fascinatingly, the motor-bus in question—'an old French one'—must have been a remnant of the fleet of charabancs run by the Société française des transports automobiles du Caucase up until the First World War! (See this page.)

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2022

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb