*

ECHOES OF THE CAUCASUS

— before the —

Altar of Mahandeo Dur

IN THE KALASH VALLEY

*

The following photographs were scanned from a copy of Where Four Worlds Meet—Hindu Kush 1959 by the great Italian mountaineer, photographer and ethnographer Fosco Maraini (1912-2004); the first English edition, translated from the Italian by Peter Green, was published in 1964 by Hamish Hamilton Ltd of London.

These particular photographs (the book is very richly illustrated) belong to Chapter 9, 'On the trail of Dionysus in Asia—An epilogue on the Kalash Kafirs'. Individually, many of them are exceptionally good photographs, but their true value lies in numbers: together, as a series, these photographs are a very rare (and singularly beautiful) record of a ceremony of shamanistic possession similar, in many ways, to those which used to be practised in Khevsureti, Pshavi, Tusheti, &c. in the Caucasus.

(The captions are original.)

|

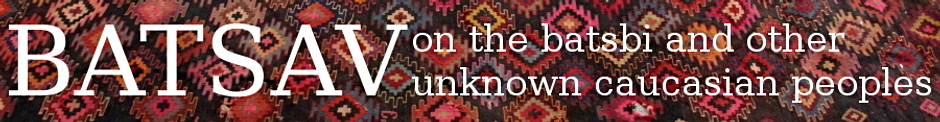

The sacred grove of Mohandeo Dur, where the Kaffirs gather for religious ceremonies and to sacrifice she-goats to the gods. |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

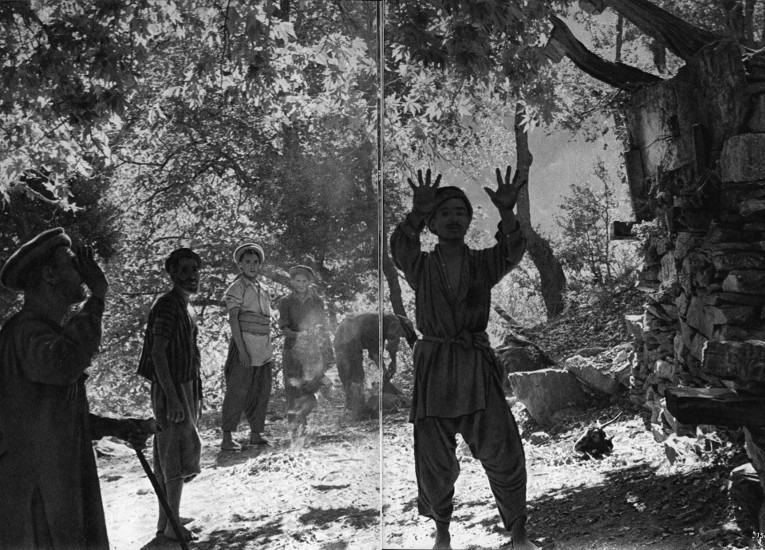

An 'on-jesta-mosh', or young male virgin, raises his arms aloft (having purified them in

the torrent) and brandishes the knife that will be used to slaughter the sacrificial goat.

Another on-jesta-mosh runs round the altar several times, with a flaming juniper-branch in

his hand; the scented smoke of this sacred tree is particularly pleasing to the gods.

The goat has been ritually slain and beheaded, and its blood poured out over the altar.

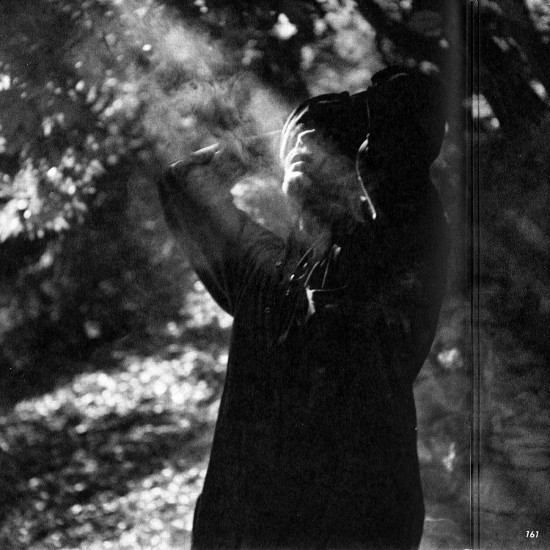

Now a shaman invokes the Shawan, or Fates, and passes into a hypnotic trance.

|

|

The shaman in hypnosis: he walks on hot coals without feeling pain, and declares, on interrogation, that he can see the Shawan. |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

|

A Kaffir altar, with roughly carved images of horses. A little below, on the wooden [panel] with the square hole in the middle, can be seen bloodstains of she-goats sacrificed to the 'all-powerful God'. [NOTE: This is not the same altar as the one depicted in the other photographs on this page.—A.B.] |

|

|---|

The best friend we made [during out stay among the Kalash people] was the pshé, or rebun, the local shaman, a lean, agile, unwashed character of about fifty. His tense, drawn features were characteristic of the man who lives on his nerves, and his great, dark, glowing eyes seemed to be looking inwards, absorbed in self-contemplation. He always carried the little ceremonial axe with the long thin handle—the badge of the Kafir elder, the man of property and consequence, with the privilege of sitting in any council where important matters are being debated. He went about with the axe on his right shoulder—exactly as we had seen it carried by those wooden images in the cemetery, set up to perpetuate the memory of outstandingly worthy citizens.

The rebun would rattle on to Murad [our interpreter] at breathless speed, telling strange, barely credible (and sometimes quite incredible) stories which Murad then proceeded to translate for our benefit. Soone the valleys became legend-haunted for us too, the scene of grotesque happenings, the home of occult powers, a background for endless chatter in which the sublime and the trivial were inextricably confused. The bahuk and shawan, and all those other beings whom (for want of a better name) we call spirits or demons, haunted every spot where the forces of nature were liable to surprise or intimidate human beings: high mountains, upland pastures beneath glaciers, lakes, sacred groves, and even—during the silent night watches—ordinary fields.

[...]

After some time we managed to persuade the rebun to sacrifice a goat on Mahandeo's altar for our especial benefit. About 8 o'clock one morning we set out from camp, complete with a wretched goat that cheerfully cropped the grass as it went along, in blithe ignorance of its imminent fate. We passed beyond the village, and walked for some three or four hundred yards through fields and thickets before turning off up a steep path that led to a well-wooded hillside. We eventually reached an extra-dense group of trees, a true sacred grove. Here the branches of holm-oak, walnut, plane and other trees had formed a kind of living grotto, a secret, whispering cave where the sun penetrated only in sharp-dappled points of light. The wind rustling through the foliage overhead sounded like the echo of a storm-tossed sea. Far away, on the other side of the valley, some shepherd was piping to himself: that familiar, mysterious and enchanting ripple of notes.

'This,' the shaman explained to us, 'is the real Mahandeo Dur.' It was, indeed, quite apparent that the sanctuary here enjoyed far greater importance than the one on the edge of the village. The altar proper was smaller (it had only two carved horses), but close to it lay a wide dancing-floor, and we also saw several long, sturdy wooden benches, large enough to accommodate a great many people. There were the usual wooden columns covered with the same intricate geometrical designs. On the branches of a nearby plane-tree numerous pairs of goats'-horns had been nailed up—presumably after previous sacrifices.

The setting, the characters, the atmosphere, all took me back with irresistible force to those stupendous opening pages of Sir James Frazer's Golden Bough, the description of the wood on the Alban Hills near Nemi, where, in the ancient thickets by the lakeside the Rex Nemorensis enjoyed a brief hour of uneasy glory—the priest-king who sat on his rustic throne only till another man dispossessed and slew him, and took his place.

Besides the shaman and his assistant, and two or three casual spectators, there were also several On-jesta-mosh, boys of fifteen or sixteen who had never been with a woman. Kafir standards of ritual purity seem to place far greater importance on male, rather than female, virginity. Two of the On-jesta-mosh, after carefully washing their hands and forearms in a nearby stream, were now standing by, rather like surgeons who have scrubbed up before operating on a patient, and are taking great care not to touch anything that could even slightly contaminate them. One of them held a sharp knife, ready to sacrifice the goat.

We were all ready, and the ceremony could begin. Someone lit a small fire of sticks, and juniper-branches (whose scent is pleasing to the Invisible Powers) were burnt on it. One of the On-jesta-mosh took a pair of these flaming branches and circled several times round Mahandeo's altar, spreading the blue, heavily-scented smoke about rather like an altar-boy producing clouds of incense in church. There were two principal celebrants, the shaman himself and his assistant—another thin, sickly-looking man. To begin with, they stood on one side, muttering prayers or formulas in a low, continuous gabble. The goat seemed not in the least alarmed: a precious attribute in the animal kingdom—only dogs seem to sense what is going to happen if someone is about to kill them. One of the On-jesta-mosh gripped the poor beast by one horn and swiftly slit its throat: in a few seconds it was dead. He caught the blood in the hollow of his cupped hands and splashed it over the altar. The goat's head was then passed through the flames, backwards and forwards, perhaps to symbolize the destruction of the offering to Mahandeo. In fact, of course, the whole carcass, body and head alike, would very shortly be cut up and divided between those taking part in the sacrifice.

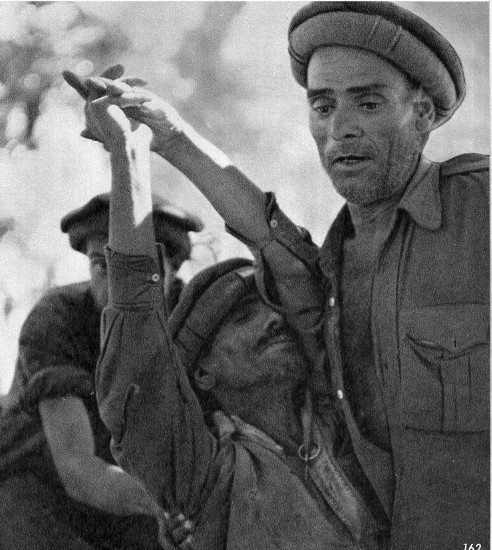

Then came the second part of the ceremony. The shaman began to whirl back and forth, uttering his invocations in a progressively louder and sharper voice. His assistant made the appropriate responses. Their dialogue became a fast, dramatic exchange. Every now and then a shaft of sunlight contrived to penetrate the dense arch of leaves and branches overhead, and shone straight on the shaman's face. He had his arms raised as he circled round, and very soon he was twisting and writhing like one possessed. Several times he trod in the still-glowing fire, without any apparent ill-effects. He gibbered and foamed at the mouth. His eyes stared sightlessly in front of him. His breast rose and fell in time with his laboured breathing.

'Now he is in communication with the spirits,' his assistant told us, gesturing nervously in his direction. 'Is there anything you would like to ask them?'

Caught thus unprepared, we asked a banal enough question (though since we had been travelling for several months, it was probably a fair pointer to our state of mind): 'Will all go well on our trip home?' we enquired. The assistant asked this question in a long monotonous chant. It would have been interesting to follow it in the original language: probably the idea was embodied in some ritual formula. The shaman whirled round several more times, and trod on the fire again. He waved his arms about, and gazed into space with wide, staring eyes, as though he really saw someone there. Laboriously, almost as though he were vomiting up undigested fragments of food, he muttered a few incoherent phrases. A moment later he collapsed unconscious into the arms of his assistant. Immediately after the embarrassing business of his coming round again, the assistant announced: 'He says all will go very well with you.' Dr. Lamberti then made a summary medical examination of the shaman, checking his pulse and some of his reflexes: he came to the conclusion that this 'awakening' from a state of self-induced hypnosis—like the hypnosis itself—was perfectly genuine.

MARAINI, Fosco, Where Four Worlds Meet: Hindu Kush 1959, London: Hamish Hamilton, 1964, pp. 266-270.

Unless stated otherwise, all materials on this website are © A.J.T.Bainbridge 2006-2014

Get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb