An account of

CAUCASIAN PEOPLES

fighting on the

GERMAN SIDE

during the Second World War

—

as well as another of the doings of

GERMAN 5th COLUMNISTS

fighting

BEHIND "FRIENDLY" CAUCASIAN LINES

(or so they hoped)

Jump to:

1. Caucasians on the German side: the Sonderverband "Bergmann"

2. German-Caucasian 5th columns: Operation "Shamil"

1.

Caucasians on the German side:

the Sonderverband "Bergmann"

Lehr-Regiment Brandenburg zBV 800 & Caucasian volunteers

1941-1944

Georgian volunteers serving in the German Abwehr's Bergmann unit salute the Georgian [Menshevik] flag.

Serving alongside them in this unit were Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Ingush, Chechens, Ossetians, Karachai, &c.

(This photograph was almost certainly taken in their training camp in Silesia in early 1942.)

NOTE:

The following was copied (freely translated) from Roland Kaltenegger's excellent Gebirgsjäger im Kaukasus: Die Operation "Edelweiß" 1942/43 (Graz: Leopold Stocker Verlag, 1997).

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

Bergmann [literally "mountain man" i.e. "highlander"] was the code-name for the deployment in the Caucasus of special units of volunteers operating under the authority of the German Abwehr's "II" [sabotage] section. The Sonderverband ["special unit"] "Bergmann" was initially made up of around 550 largely untrained men from both the North and South Caucasus (émigrés and prisoners-of-war from the region) serving around a core of roughly 200 German soldiers with different specialist skills, but would later grow to a peak of around 3,000.

The Sonderverband was created in November 1941 in the "Stranz" Lager of the training camp in Neuhammer-am-Queis in Silesia [now Świętoszów in Poland, 120km N.E.E of Dresden]. A small core of German instructors had been assembled here, many of them Russian-speakers belonging to the Lehr-Regiment Brandenburg zbV 800, who were to teach infantry combat and tactics to the Caucasian troops. The latter were initially given captured French uniforms, but were soon allocated Wehrmacht ones. Five companies were created along ethnic lines. Noteworthy was the fact that the military oath these men were asked to swear did not include the usual oath of fidelity to Hitler: this exception, the result of Admiral Canaris's influence, was further proof of the unit's political autonomy. It was also explicitly ordered that the Sonderverband be supplied with weapons and equipment equal in quality to that of any "normal" Wehrmacht unit. The unit was unquestionably under the authority of the Abwehr under Canaris.

The Commanding Officer of the Sonderverband was no less a figure than Hauptmann Professor Dr. Dr. Theodor Oberländer—a scientist and academic sympathetic to the Nazi cause from its very beginnings in 1923, and with a dubious war record to say the least. Oberländer was one of Nazi Germany's greatest experts on "the peoples of the East" (i.e. Eastern Europe and the Caucasus), and had already served as the political advisor to a unit of Ukrainian volunteers fighting on the German side—the controversial "Nightingale" Battalion. This experience was to serve him in good stead, and made him an ideal candidate to oversee the creation of a similar, Caucasian formation.

(Oberländer was, despite some accusations of his having been complicit in various war crimes, later fast-tracked through "denazification" by the Americans, who were no doubt grateful for his co-operation; he subsequently entered politics and parliament and later reached federal ministerial rank under Adenauer.)

In his The East and the German Wehrmacht: Six Memoirs from the Years 1941-1943 against the National-Socialist Colonial Theory ("Der Osten und die Deutsche Wehrmacht: Sechs Denkschriften aus den Jahren 1941-43 gegen die NS Kolonialthese"; Asendorf: MUT Verlag, 1987; p. 138 onwards in Kaltenegger's book), Oberländer writes:

On the 14th of October 1941 I was ordered to report to AOK XVII [headquarters of the 17th Army Group] in Poltava, where I was asked if I would be willing to command a unit of Caucasian volunteers. I was being considered as a possible candidate for this position due to my earlier travels in the Caucasus and my past experience with volunteers [in the Ukraine]. To me, the initial condition was that the kinsmen of foreign peoples serving [on the German side] be treated with the utmost respect for their independence and autonomy; this view was espoused by Abwehr II; Admiral Canaris himself stood by it.

Having listened to my concern that the Caucasians would react very badly to any limitations to their personal freedom and to the repressive measures which were later unfortunately ordered by the [National-Socialist] Party and the State during their deployment in the field, Oberst Winter answered that the Abwehr was familiar with the problems of psychological warfare and that this was precisely why he would be pleased to place the unit under the command of the Abwehr. Successfully deploying a unit of this kind was one of the few ways in which [Germany's] political leadership could be brought to treat the populations of occupied territories favourably.

The experience of Abwehr II had shown that, if they were well treated, prisoners-of-war [POWs] who decided to change sides could easily and effectively be deployed in company-sized or even larger units, just as long as they felt that they would be correctly treated and sufficiently cared for.

The result of this conversation was the decision to set up such a unit in battalion strength, with a view to deploying it along the Georgian Military Highway and over the Cross Pass towards Tbilisi.

Anybody who has crossed the Caucasus along the Georgian Military Highway knows that a well-organized defence can turn the road into an insurmountable obstacle. The area on both sides of the Highway is populated not by Russians but by Georgians, [a nation] whose thirst for freedom and anti-Bolshevik and by extension anti-Russian feelings were quite clear even in Poltava. After the bitter experience of Nachtigall ["Nightingale"; see above], which was disbanded by Admiral Canaris in Jusmin following Hitler's declaration that 'no Ukrainian may take part in his own liberation', and considering the difficulty of the task, the central question was now: Would the OKW be able to guarantee that the members of the planned unit would be properly and justly treated and that their political goals would be realized? Crossing the Caucasus would no doubt be such a difficult and militarily costly task, that volunteers from the region would only come forward if they were sufficiently confident of being given a role to play in the future reorganization of their homeland. The creation of such a unit with men from the side-valleys of the Terek Valley, from the very region through which the Georgian Military Highway passed, certainly promised a significant advantage, and would be an important step towards preparing for [future operations in the South Caucasus].

The main obstacle to the creation of such a unit was obvious. Again and again, the NSDAP, the SS and the SD opposed the creation of a unit which, although militarily useful, could not after its goals had been achieved be disbanded without seriously damaging the political goals of the two parties—that of the liberated people and that of the liberating power alike.

Bergmann was essentially created on the 14th of October 1941. The task before us was clear and we began our search for the Caucasian volunteers and the cadre of German soldiers we needed. Although the prisoner-of-war camps offered a vast multitude of POWs from which to choose, the choice was not an easy one. POWs were never forced to volunteer, nor were conditions in camps made worse in order to "encourage" them. [...] We were not interested in those who hoped to improve their situation by volunteering [to fight on our side]. We needed quite a different kind of man. We needed men who valued freedom above all else, who were true to their nation or to their clan and who showed clear anti-Bolshevik feelings. During the many conversations we had with POWs we learned that over the years almost every single family had lost a loved one to Bolshevism. There were naturally informers working for the other side in the POW camps, but [all the prisoners] knew who they were. And so when someone more or less openly declared himself to be against Bolshevism and otherwise met the physical requirements, he was taken aside. The unit's success depended upon a single word: trust. It was impressed upon the German [officers and instructors] from very beginning that earning these men's trust would be decisive. [...]

As soon as the POWs saw that we treated them as equals, that we took their national and religious characters into account, that we ensured that they were issued with supplies and taken care of and that they would become fully-fledged German soldiers, bound together in a brotherhood which in those days was self-evident in the German Wehrmacht, they began to trust us and let themselves be won over [to our cause]. The first conversation was often decisive—particularly given the fact that we were not asking them to betray their country, to fight against their homeland, but rather to fight a [state] which had caused much blood to be shed in the Caucasus, especially as a result of its fight against the self-determination of the region's inhabitants.

Around 800 Caucasians of various nationalities—mostly Georgians, Azerbaijanis and Armenians, but also men from smaller nations such as the Ingush, the Chechens, the Ossetians and the Karachai—were thus assembled in October 1941 and sent out to help with the harvest as a team-building exercise. This short transitional period, during which the Caucasians no longer felt that they were prisoners, worked out very well. The overseer was a German whose parents owned land near Tbilisi and who had already served as a cornet-player during the First World War with the Bavarian Corps of General Kreß v. Kressenstein in Georgia. He earned the Caucasians' trust very quickly.

On the 3rd of November 1941 these 800 men were taken to Germany, where they were grouped together in a unit on the 16th of November in Neuhammer-am-Queis [now Świętoszów in Poland; see above]. The creation of this unit and its equipment had been minutely planned in Berlin; all that was now left to do was find the German soldiers who were to serve as the unit's cadre. The unit's future effectiveness and its successful prosecution of difficult military objectives rested entirely upon the quality of this cadre, and, once again, only volunteers were considered for this role—officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) alike. Knowledge of [Russian] was desirable but not imperative. And so volunteers arrived from all over Germany—men who had volunteered for a special task, but who now found themselves in Neuhammer-am-Queis face to face with a group of men who had for the past 24 years been brought up in a completely different way from the usual German infantryman. Many of the instructors expressed shock and dismay when they first set eyes on their new charges, who were so very different from the model German soldier. In order to equip the German officers and NCOs with the understanding and patience they would need to earn the men's trust, weekly talks were held on a variety of subjects: the history of the Caucasus, the region's 30-odd peoples, the fight for freedom against Imperial Russia, Russian policies of assimilation, the politics of Bolshevism, the national and religious idiosyncracies of the various groups, &c. Attendance at these talks was compulsory for the entire German cadre; the hope was that this would help them understand and relate to the men, who themselves stood before an equally challenging process of having to adapt to new surroundings. Five companies were created: the 1st, 4th and 5th Georgian; the 2nd North-Caucasian; the 3rd Azerbaijani; and an Armenian column.

The place of birth and local knowledge of every man was meticulously recorded. Besides the 1941 POWs, a group of around 70 Georgians who had emigrated to France in 1921 following the Soviet invasion of their country and had subsequently served in the French Army were also an interesting and valuable addition to the unit. They now met fellow Georgians who had experienced 20 further years of Bolshevism in their homeland. They spoke French and were well trained militarily-speaking (some of them having reached officer rank in the French Army), and were pressed into our service as NCOs and officers. All wore the German uniform. For a short while the Caucasian officers were issued with improvised insignia, until they too became indistinguishable from German officers.

Three Soviet officers who had earlier been mistakenly interned in a POW camp [Straflager] were also added to the emigrants. A higher military authority called us to ask whether or not we might be willing to accept responsibility for these three men, as they obviously had cause to resent the wrong way in which they had been dealt with. It speaks volumes about the unit's esprit de corps that these three officers, apparently so obstinate and belonging as they did to three different nationalities and professing three different faiths, quickly integrated with the others and went on to distinguish themselves in the fight against the enemy.

Training in Neuhammer was incessant and everything was coming together. All those who came to visit the unit towards the end of December 1941 were forced to admit that these men from the Caucasus, divided as they were into dozens of groups along ethnic and religious lines, were overcoming their differences in preparation for a great task whose importance and necessity they were all equally convinced of.

Another 50 Azerbaijanis arrived around mid-January 1942, as well as different Caucasians from various POW camps in February. The German cadre continued to be taught about the Caucasus, and the unit prepared itself feverishly for its first operation. They swore their first oath on the 10th of March 1942. Following the experience of Nachtigall, it was even more difficult this time to find a wording which would satisfy both the OKW and the Caucasians' thirst for freedom. The oath finally contained the decisive line 'in the fight for the liberation of their homeland'. On the 20th of March a Japanese delegation led by Colonels Shibuti and Yamamoto paid us a visit. The two were astounded by the unit's esprit de corps and discipline, and were amazed to see that it was indeed possible to make soldiers out of POWs.

The unit basked in its new-found prestige. The proponents of the political theory, which held that we could only free Russia from Bolshevism with the help of the Russians or of the different peoples of Russia, pointed to the psychological successes visible in the Bergmann unit. [The unit's growing fame] naturally also attracted opponents, and the way the wind was blowing in Berlin could be felt as far as our parade ground.

If the unit was to achieve its objectives, then training them in Neuhammer's infantry school in the flat expanses of Silesia would simply not be enough: it was absolutely vital that the men receive as much instruction as possible in high-altitude mountain warfare. After long negotiation, the Luttensee training camp by Mittenwald [on the German-Austrian border, 22km N.N.W of Innsbruck] was secured for the unit; the men arrived on the 26th of March 1941. Our colleagues from northern Germany were quite impressed by the height of the Karwendel Ridge [immediately to the south of Mittenwald, rising to 2,400m]. Luttensee's camp and training ground were at Bergmann's exclusive disposal. The Caucasians felt much more at their ease in this mountainous area, and were to some extent "back home". We also discovered a training area which resembled the Terek Valley through which the Georgian Military Highway passed, and prepared a live-fire exercise against a simulated enemy force [eine Übung mit Freund und Feind und scharfem Schuß]. The men swore their second oath in Luttensee on the 1st of May 1942. On the 20th we conducted an exercise up the Karwendel Valley with General Hähling and other high-ranking officers from the OKW in attendance. Thanks to the relentless work of the German cadre, the unit had by now reached quite a high level of training.

Two difficult problems presented themselves to the unit's leadership in June 1942: Firstly, General der Reserve von Niedermayer planned to use the Sonderverband Bergmann as a core around which to build up the Mohammedan Legion he had been tasked with creating. I was ordered to report to Mirgorod, where I found a completely disorganized rabble of Mohammedan POWs. The psychological challenges posed by the need to treat these men and any units they might compose in an exemplary, friendly manner, which had stood at the heart of Bergmann, had so far been given only the slightest of consideration. Any thinning of Bergmann, any attempt to carve it up, would have meant the end of the unit. The date of the unit's disbandment was set for the 22nd of June, but on the 23rd in the Headquarters in Lötzen I learnt that the order had been countermanded. The unit's unity had been saved [Die Einheit der Einheit war gerettet]. But back in Luttensee another calamity awaited us. [It transpired that] Tsiklauri, a former Red Army captain, was conspiring to create a small group [of traitors] who might conceivably have caused the unit great damage. Noteworthy is the fact that this group was largely rejected by the Georgians and that its activities were reported to headquarters in a timely manner. Their condemnation by court martial in Garmisch brought their attempt to an end. I gave evidence as a witness during Tsiklauri's court martial in Garmisch on the 27th of June.

[...]

Admiral Canaris, the head of the Abwehr, paid us a visit on the 7th and 8th of July 1942. He wanted to see our military capabilities for himself shortly before our planned deployment to the Caucasus, and we showed him what we had learnt over a variety of different terrain. The unit received its marching orders for the front in July-August.

In the meantime, the fast-moving German Panzer units had reached the plains along the lower reaches of the Terek River Delta. Although all the peoples of the region had been crossing the Caucasus Mountains by going around their eastern edge for around 2,000 years, the Germans ordered their mountain troops to follow the difficult western route along the Black Sea and over the central Caucasus. It came as a surprise to no-one that they were stopped well before even reaching Sukhum, Maikop and Tuapse and that they suffered heavy casualties in the high mountains.

We arrived in Pyatigorsk on the 25th of August 1942 and battalion Headquarters (H.Q.) were set up in Rusky II [perhaps the twin villages of "Russkoye" 12km N. of Mozdok in North Ossetia?] on the 28th. The unit would essentially continue to occupy this position until the 21st of December. Our left flank facing the Caspian Sea was open, unprotected, forcing us to reconnoitre across the steppe, where one day with the help of artillery support we succeeded in destroying a Russian armoured train as it stood motionless on a new and to us hitherto unknown stretch of track towards Kizlyar. Our platoon of combat engineers, the so-called "S-Column", distinguished itself particularly on that occasion. On our right flank we were in contact with friendly elements of 52nd Corps, namely the SS-Standarte [2] "Germania" for the time being. ["SS-Standarte" was an early name for a Waffen-SS division; the term was obsolete, officially abolished in 1940, and it is therefore unclear which SS unit Oberländer is remembering.] The training and instruction [the men had received in] Neuhammer and Luttensee proved itself vitally useful during this period. In front of our trenches grew sunflowers and fields of cotton. The Soviet positions were 2km away, and behind them rose the foothills of the Caucasus. On some fine days we could gaze upon the entire range, particularly Mt Kazbek. Although the Red Army units south of the Terek River were not completely cut off from the [main body of the Red Army], their only line of communication ran along the shores of the Caspian Sea and up the Volga River; the Soviet divisions [facing us] were made up not of Russian troops but almost entirely of Caucasians.

When, in the evenings, the Georgians gathered in front of our positions to sing their military songs [Kampflieder] in choir, their fellow-countrymen in the Soviet division [facing us]—whose political commissar, Suslov, was the future head-theoretician of the Soviet Union—listened in. Every one of us remembers those balmy summer evenings, when individual deserters crossed over to our lines through fields of sunflowers or cotton, to be greeted by fellow-countrymen wearing the uniforms of German officers or NCOs and made to feel welcome with good German Schnapps. We had no need to disarm them immediately in such cases for they [and the Georgians in our unit] often quickly fell into each other's arms, being from the same village or related or having gone to the same school together. Also none of them were asked to explain themselves, for others who had barely one or two years ago been serving in the Red Army in Tbilisi now wore German uniforms and served as NCOs in the German Army. We also gave every one of them the opportunity to [change his mind and] return to his [Red Army] unit, for we knew what [beneficial] effect that might have. In a few days around 800 men from the Georgian Division facing us crossed over to our lines—among them an entire [artillery] battery, complete with battery commander and his wife. The timing [of these defections] was often quite fraught with risk. As they would always cross over to our lines under cover of darkness, our men were told to hold their fire during the night. An artillery barrage was always kept in readiness, just in case, but all our precautions turned out to be unnecessary.

One sunny morning we watched as vast clouds of dust billowed up into the air from behind the enemy positions facing us. Although this was obviously caused by the movement of a large column of enemy vehicles, we could not account for such a movement. In the afternoon, however, we discovered the reason: the Georgian "Suslov" Division had been recalled because of its [perceived political] unreliability, and had been replaced by an Azerbaijani division. We had to change the choir, the Georgians having lost their powers of persuasion.

It should be added here that the catastrophe of Stalingrad was already slowly unfolding during these stages of the war. There was no doubt that Soviet propaganda was trying to make good use of the possibility of defeat at Stalingrad in every way it could. During a visit to H.Q. in Pyatigorsk I had the opportunity to study the main map of operations [on the Eastern Front], and saw for myself the extent to which the situation was becoming serious. As I was returning to [the Bergmann unit] I met an Azerbaijani major belonging to the new division opposite us, who offered to defect with his entire battalion and fight alongside us. What to do? The level of human responsibility was enormous, but who could have refused such an offer?

Nalchik was captured towards the end of October, extending our section of the frontline in the steppe from our left flank in Galyugaevskaya to the east [on the northern banks of the Terek River, c. 25 kilometres E.b.S of Mozdok] all the way to the west, far beyond Nalchik. Our [unit's] section of the front was 40 kilometres.

[Some time later] I was ordered to report to Gen. Feldmarschall von Kleist in Stavropol. Feldzeugstab ["ordnance staff", apparently] 205 placed a Fieseler Storch at my disposal, and a few hours later I stood before Gen. Feldmarschall von Kleist, General Köstring [at that time "Commissioner-general for Caucasian Affairs"] and von Kleist's Orderly; the latter recorded this meeting in his diary. My reception was icy. I felt as if I were on trial. Just before the Gen. Feldmarschall sat down to [lunch? dinner?], von Kleist asked me: 'Since when is it acceptable to criticize my commanders?' I answered that I did not know what he meant, but that I myself would certainly allow a Hauptmann [to express such views] in the performance of his duties if the matter concerned questions of humane treatment and human rights [Fragen der Menschlichkeit und des Rechtes]. Kleist: 'Where in my army are hundreds of prisoners shot?' I drew out my diary and read him the figures I had for prisoners shot or dead. Kleist immediately ordered a court martial; he made us responsible for monitoring POW camps within his command behind the Caucasian Front, and granted us permission to place an observer in every camp. We selected the best men from our unit and were able to work very successfully in the POW camps. Even individual Caucasian Jews who had defected across our lines were not handed over [to the authorities set up to "deal" with them], and were instead pressed into service [on equal terms with other volunteers].

Maintaining the cadre of German officers and men also presented difficulties, given the losses the unit had sustained during operations in the Caucasus and along the Terek River and the paucity of replacements. [Another source of difficulty was the fact that] this cadre, which was initially intended to serve as the backbone for 5 companies, now had to be divided up among 12 companies and 2 squadrons. Most of the sergeants and NCOs were now Caucasians. Those volunteers who had newly joined us swore their oath of fidelity on the 21st of December 1942. On the 23rd, Soviet paratroopers were dropped near Nalchik dressed in German uniforms bearing the insignia of the Sonderverband "Bergmann" and with perfectly forged identification papers. They had secreted themselves in a farm on the outskirts of Nalchik and some of them had ventured out into the town, where they were detected by almost pure chance—particularly as [Bergmann's] companies were still relatively new and the men had not had the time to get to know their colleagues in neighbouring units. The entire group [of Soviet paratroopers] was taken prisoner within a few hours of their landing.

It is important to bear in mind the difficulties the unit faced at the time. Casualties—killed, wounded or through illness, mainly sustained in the Caucasus—had whittled its original strength of 1,100 men down to 900. [During the unit's deployment along the banks of] the Terek River, new volunteers had swelled its numbers to 2,883 i.e. the triple. Uniforms, weapons, supplies—everything was taken from the enemy. When "Old Fritz" [der Alte Fritz was the nickname of Frederick II ("the Great") of Prussia; Oberländer is probably referring to "Old Man Hitler"] ordered his men to arm themselves with captured enemy weapons, [besides weapons we would also bring back new recruits]. We were divided into 12 companies and 2 squadrons [Schwadronen]; we deployed several of our companies in the town of Nalchik, and were partly responsible for their security.

Thus did the unit continue to be built up in the face of the enemy front lines during the months of October, November and December. As the situation in Stalingrad worsened, the minds of our Caucasian troops were resolutely focused upon their homelands, which they wanted to liberate. The possibility of having to retreat was simply unimaginable to them. Christmas 1942 drew near.

The unit celebrated Christmas Eve on the 24th of December 1942, unsure of what the future held for us. Even every waking hour of the days between Christmas and the New Year was devoted to further training.—On the 31st of December, Bergmann's commanding officer was ordered to report to the forward H.Q. of the neighbouring German infantry regiment, where he was informed of the general order to retreat from the Caucasus. New Year's Eve was to be the decisive turning point of Bergmann's story. The disaster of Stalingrad unfolded. The danger of the [German forces in the Caucasus] being cut off around Rostov was felt to be so great that the entire Caucasus was to be evacuated. The order to retreat also stipulated that all the ammunition in the area of operations was to be expended; the guns fired all night long. We tried to explain the necessity of this course of action to our men, but met with little understanding.

We spent our last night, New Year's Eve, in our positions. Then the long retreat began, and we were in luck: heavy fog hung over Grozny for days on end, and the Soviet air force was unable to take off and hinder our retreat over the Malka and Terek Rivers and other bridges. We retreated on foot. In Solskoye [perhaps the village of Zolskaya, c. 25 kilometres S.E. of Pyatigorsk?] we had our last view of the summit of Mt Elbrus gleaming in the sun through the crisp morning air. The unit moved on, winding its way like a snake through the landscape. Despite the retreat and the dire overall military situation, The extent to which military discipline was preserved, despite the retreat and the dire overall situation, was surprising—even in the entirely new companies, which had had barely enough time to begin building up an esprit de corps. The local population welcomed us, and regretted our departure. Besides the Cossacks and the Cherkess, I remember many conversations with other [ethnic groups], who deeply deplored our retreat.

The [winter] weather favoured our movements. Snowfall was moderate, and the roads were so frozen that we were able to cover relatively great distances on foot during our daily marches. Enemy pressure along our section of the front was slight; only very weak enemy forces can have been facing us in late December 1942, else our retreat would have been much more difficult. It took the men of Bergmann all of the month of January to retreat on foot from the banks of the Terek River all the way to the Taman Peninsula [a distance of some c. 600 kilometres as the crow flies], which we finally reached on the 6th of February 1943. [...]

Having retreated from the Caucasus, the unit spent weeks on the Taman Peninsula. It became increasingly difficult to [feed the troops]. We were surrounded [by advancing Red Army units] and helped neighbouring engineer battalions to improve the local paths and tracks. We had enough sheep [to eat], and whenever we broke a hole through the ice, we would bring up a bucket full of fish instead of water; but bread alone is not enough to survive, and protein alone is even worse. Our diet was rich in protein but lacking in carbohydrates; the number of cases of infectious jaundice increased considerably—but only among the Germans, and not the Caucasians, who criss-crossed the Taman Peninsula's vegetable patches and ate enough of the vital garlic. An order stating that troops were to eat a clove of garlic a day quickly brought an end to the outbreak of jaundice.

[...] On the 22nd of February 1943, the unit was transported [across the straits] to the Crimea in assault boats and towed gliders, all motorized vehicles and heavy weapons having been ordered to be left behind.

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

POSTSCRIPT

|

|

|

|---|

The controversial involvement of Georgians on the German side during World War II made newspaper headlines in America in 1993 following President Clinton's nomination of General John Malchase David Shalikashvili (✝ 1936-2011; Georgian: ჯონ მალხაზ დავით შალიკაშვილი), then the Supreme Allied Commander of NATO Forces in Europe (SACEUR), to become the new Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He was the first foreign-born soldier to attain such rank, having worked his way up the entire chain of command. Shalikashvili's father, Dimitri, shown here in Polish uniform, had served in the German Army's Georgian Legion during the war before moving to America.

Melissa Healy of the Los Angeles Times wrote at the time:

WASHINGTON, AUGUST 28, 1993 — The father of John M. Shalikashvili, the Army general nominated by President Clinton to become America's chief military commander, served as an officer in an elite Nazi military unit during World War II, according to information released Friday by a Jewish research institute.

The late Dimitri Shalikashvili, referred to by Clinton simply as a "Georgian army officer" when the President announced the nomination earlier this month, became a major in the Waffen SS in 1944, according to Rabbi Marvin Hier, director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles.

Information compiled by the center, which collects historical data to help track down Nazi war criminals, indicates that the elder Shalikashvili's association with the Nazis began after the family fled Poland in 1939 ahead of the Soviet Army's westward advance.

On the basis of the father's own unpublished memoirs--on file at Stanford University's Hoover Institution--Hier said it appeared that the senior Shalikashvili began collaborating with the Nazis in 1941, and perhaps as early as 1939, after the Georgian-born officer was released from a German POW camp in Poland. Following his release, he began organizing the Georgian Legion, a force of expatriates intent upon liberating Georgia, with German aid, from Soviet control.

The allegation appears to hold little risk of derailing the nomination of Shalikashvili to become chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff--a rise through the ranks that Clinton hailed as "a great American story."

But it could raise questions about how the family was able to enter the United States in 1952, and how much Clinton knew about the senior Shalikashvili's wartime activities when he named his son to the nation's top military post on Aug. 11.

"What is relevant is that Gen. Shalikashvili has done a great job at NATO and that he'll make a magnificent chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff," Sen. Carl Levin, (D-Mich.), a lawmaker noted for his efforts to promote awareness of the Holocaust, said Friday. As a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Levin will be a key supporter of Shalikashvili's nomination.

It was not immediately clear whether the White House knew the full details of the father's wartime service when Clinton decided to nominate Shalikashvili to succeed Gen. Colin L. Powell. Officials acknowledged that they knew the senior Shalikashvili had served in the German army, but rejected suggestions that he was an active Nazi sympathizer.

White House spokeswoman Ricki Seidman, echoing Levin's remark, declared Friday that the younger Shalikashvili's "record stands on its own, and his father's history is not relevant." Defense Secretary Les Aspin, in a statement released by the Pentagon, praised the nominee's "superb record of achievement" and added that "allegations about his father's history are not relevant to Gen. Shalikashvili's nomination."

Gen. Shalikashvili's office in Belgium could not be reached for comment on when his father died. According to Hoover archivist Anne Van Camp, the elder Shalikashvili's widow donated the manuscript in 1980, some years after her husband's death. Van Camp confirmed that Hier's account of the memoirs accurately reflects their contents.

Hier emphasized that in releasing details of Dimitri Shalikashvili's memoirs, the Wiesenthal Center does not oppose the nomination of his son, whom he called a "patriotic American" who deserves to be judged on his own merits and deeds.

"Going after 8-year-old refugee boys is not what we're after at all," Hier said in an interview. "We respect very much the fundamental American principle that every person should stand on his or her own deeds and accomplishments, and should not be held liable for the actions or misdeeds of their parents or anyone else."

According to his own account, Dimitri Shalikashvili became a member of the Waffen SS in 1944, when the Georgian Legion was subsumed into the elite Nazi organization. Until then, the legion, one of several national units organized and armed by the Nazis, had been under the command of the regular German army. The consolidation followed a key attempt on Adolf Hitler's life, Shalikashvili wrote.

The Waffen SS was the most trusted arm of Hitler's army in World War II. Hier said that several of the foreign units that operated under Nazi command committed terrible atrocities during the course of the war. Collaborating units of Ukrainians, Latvians and Lithuanians assisted in rounding up Jewish and other prisoners and, in some cases, in murdering them. But Hier stressed he had no evidence that the Georgian Legion engaged in atrocities.After World War II, the U.S. government officially barred the immigration of individuals who had knowingly cooperated with the Nazis--a prohibition that would probably have blocked the entry of the Shalikashvilis into the United States. The policy is known to have been waived in many cases where Nazi collaborators had special technical or military knowledge that could prove useful to the United States in its prosecution of the Cold War.

Recounting his efforts to enter the United States after the war, the senior Shalikashvili made clear that because of his activities, he probably would have been turned away if he had applied to the International Refugee Organization for entry into the United States. "I made no effort to get a visa through the IRO, as we had relatives in the United States, and they were willing to help us," wrote Shalikashvili.

After an American cousin offered a sworn statement on the family's behalf, the Shalikashvili family settled in Peoria, Ill., when John Shalikashvili was 16. Six years later, the younger Shalikashvili's U.S. military career began, when he was drafted into the U.S. Army and trained as an artilleryman.

2.

German-Caucasian 5th Columns:

Operation "Shamil"

Maikop & Grozny

Lehr-Regiment Brandenburg zBV 800 & Caucasian volunteers

25th of August 1942—10th of December 1942

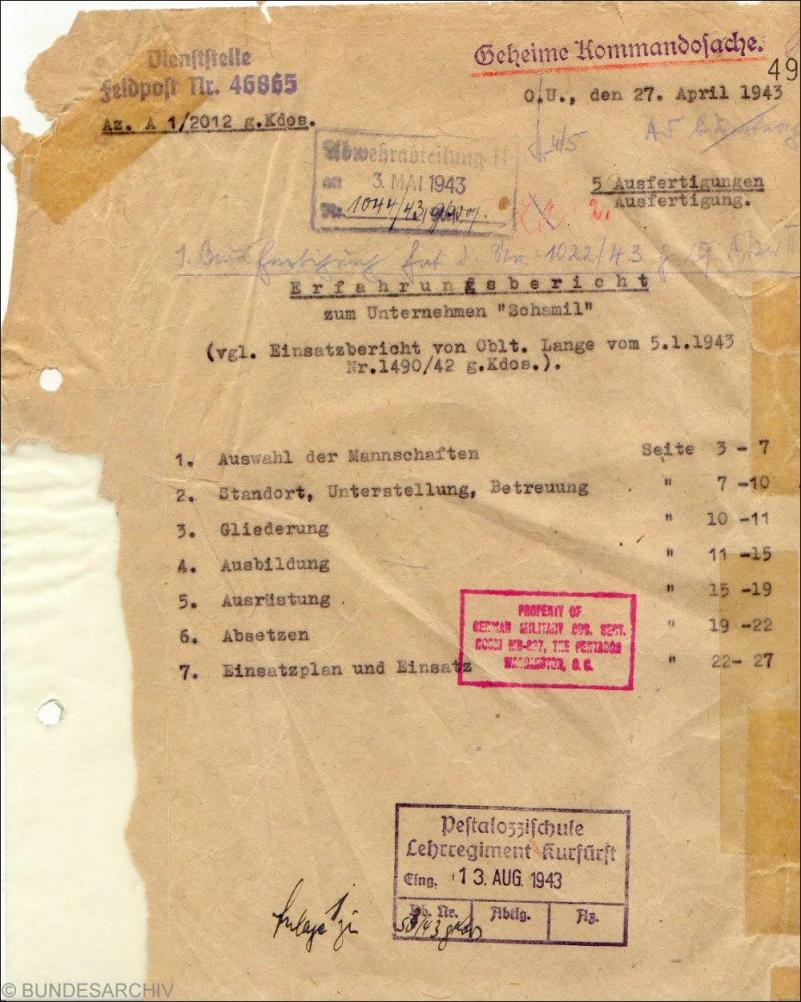

The cover of the German Army's official "lessons learnt" report on Operation Shamil

(German Federal Archives; click to open a slightly larger version)

In August 1942, a unit made up of hand-picked men belonging to the extraordinary Lehr-Regiment Brandenburg zBV 800 (the "Brandenburgers"—perhaps Germany's most unorthodox and unconventional special forces) and "local" volunteers recruited from among Soviet prisoners of war were inserted by air far in front of the Wehrmacht's main forces, i.e. behind enemy lines, where they were to aid the German summer offensive's (positively lunatic) efforts to reach and secure all the oilfields of the Caucasus as far as Baku.

Although technically under the authority of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (i.e. the German Army), the Lehr-Regiment Brandenburg zBV 800's speciality was being deployed in enemy territory to carry out all manner of special operations, and in that capacity the unit had "belonged" to Germany's Abwehr (counter-intelligence i.e. the IIIrd Reich's secret services) since its creation before the war. At the time of "Operation Shamil", the Brandenburgers' commander-in-chief was Oberstleutnant [Lieutenant-colonel] Paul Haehling von Lanzenauer.

Furthermore, and despite the fact that they took place in the North Caucasus, the activities of these secretive units—which were deployed around the oilfields of Maikop and Grozny (the capitals of Adygea and Chechnya, respectively)—tend to be absent from history books on this theatre of operations, which quite understandably and almost without exception focus upon the high-altitude efforts of the 1st ("Edelweiß") and 4th ("Enzian") Mountain Rifle Divisions of the German Army's 49th Mountain Corps to advance over the western end of the Caucasus Mountains and push down to the Black Sea coast.

THE PLAN WAS, specifically, for two small forces of Brandenburgers and Caucasian volunteers to be inserted by air close to Grozny and Maikop. There, they where to make contact with Muslim (primarily Chechen) organizations and freedom fighters willing to help them fight the Red Army, cobble the latter together into makeshift groups and open a "second front" behind enemy lines, attacking and securing state and strategic targets and pinning down Red Army units to aid the advance of the bulk of the German Army, which was pushing forward from the north-west and was expected to arrive "shortly".

NOTE:

The following was copied (freely translated from the original German) from MÜLLER, Rolf-Dieter, "Gebirgsjäger am Elbrus: Der Kaukasus als Ziel nationalsozialistischer Eroberungspolitik", in CHIARI, Bernhard, & PAHL, Magnus (eds), Wegweiser zur Geschichte: Kaukasus—published in 2008 by the Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh GmbH & Co. KG in Paderborn on behalf of the German Army's Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt ("MGFA").

"OPERATION SHAMIL", 1942

As part of their preparations for operations in Russia, the Abwehr's foreign section prepared plans to encourage the peoples of the North Caucasus to rise up against their Soviet masters. The idea was to harness their dissatisfaction and to move them to armed resistance against the Red Army. At the initiative and under the command of the Abwehr's Lieutenant-Colonel (Reserves) Erhard Lange, the planning of a special operation was undertaken which was to be named after the Imam Shamil, who in the XIXth century led an army of Muslim highlanders from Daghestan and Chechnya against the Russians and inflicted several crushing defeats upon them.

Lange's plan was for him and a small group of highly-trained soldiers to be dropped by parachute behind Russian lines in the Caucasus, and to persuade as many of the region's peoples as possible to rise up against the Soviet authorities. The core of his unit was made up of experienced mountain troops from South Tyrol and Russian-speaking men from the Baltic which he had chosen from among the ranks of the "Brandenburg" Regiment. The rest of the unit consisted of volunteers from Chechnya, Ingushetia and Daghestan who had become prisoners of war at the start of German operations in Russia and were now coming forward to help free their homelands from Soviet rule.

At the end of July 1941, Lange assembled the forces at his disposal and made them undergo a rigorous course of training which would last almost a year and mostly took place in high mountainous regions. On the 28th of June 1942 the German Army began its great summer offensive along the southern half of the Eastern Front, whose main goal was the capture of the North Caucasus's oilfields. Lange's unit was moved to Stalino a few days later, and was flown towards its drop zone on the night of the 26th of August. After assuming that they were over their drop zone some 30 kilometres south of Grozny, the men jumped from a height of over 2,000 metres.

Because they had jumped from such a great height, the commandos landed far from each other—many being forced to fend for themselves for days—and around 85 per cent of their supplies were lost. When the sun rose that morning, the soldiers discovered that they had landed far from their intended drop zone. Even with the help of the local population it took several days for the unit to slowly regroup. Helped by farmers, tribal leaders and local resistance groups, the commando unit was able to constantly move from one safe placed to another and thus evade the Soviet units which had been ordered to comb the region for them.

The unit's original mission was clearly in jeopardy. Contact with headquarters could not be maintained as the unit had lost most of its communications equipment during the parachute drop, and the batteries of the only functioning radio set were flat sooner than had been expected. The commando also lost several men during repeated fire-fights with Soviet patrols, and Lange and his remaining men were finally forced to try to fight their way back to the German lines. On the 10th of December 1942, after a march of around 550 kilometres, the soldiers finally reached friendly German units by the village of Verkhniy-Kurp to the west of Malgobek. Lange filed a complete report on the operation shortly afterwards, but the start of the German Army's retreat from the Caucasus a few weeks later quickly rendered its recommendations academic. The initial plan to encourage uprisings against the Soviet authorities by means of "Shamil" and possibly other special operations was abandoned. Lange was awarded the Knight's Cross for the operation, which propaganda turned into a victory.

Franz Kurowski's Deutsche Kommandotrupps 1939-1945: Brandenburger und Abwehr im weltweiten Einsatz (Stuttgart: Motorbuch Verlag, 2000) also mentions the operations of other "5th column" German units around Maikop:

The newly-created 8th Company of the Brandenburg Regiment under Leutnant Prohaska was dropped—along with other smaller units commanded by Leutnant Adrian von Foelkersam—by parachute close to the town, where they were to seize and hold various strategic points to secure the German Army's advance. 8th Company, for example, apparently captured a road bridge by Bataisk; Leutnant Prohaska fell during this operation, and he was posthumously awarded the Knight's Cross. [Note: The only Bataisk I could find is near Rostov-on-the-Don, some 300 kilometres to the north; Rostov and Bataisk are indeed linked by a road bridge; perhaps Kurowski was confused?]

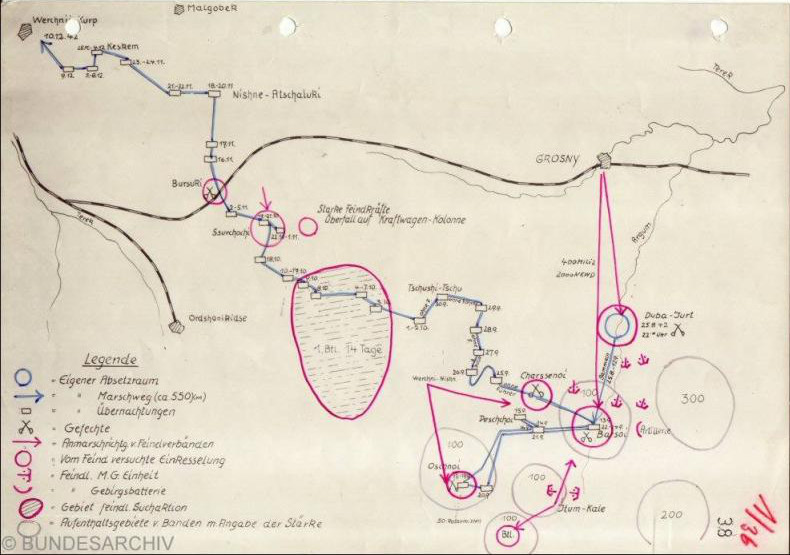

Probably the only surviving map of "Operation Shamil"

(German Federal Archives; click to open a slightly larger version)

Key:

Blue circle: own point of insertion

Blue arrow: route of own progression

Small rectangles: nights

Crossed swords: fire-fights

Red arrow: enemy advance

Red circles: attempted encirclement by enemy forces

Red "T" with dots: enemy machine-gun nests

Red curve: enemy artillery positions

Red circle with hashing: area of enemy search activities

Grey circles: position of resistance groups with indication of their strength

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

ACCORDING TO THE MAP the Brandenburgers and the Caucasian volunteers were parachuted a mere 30 kilometres south of Grozny by the small Chechen village of Duba-Yurt, where the Argun River, having cut its way through 100 kilometres of rugged, densely forested mountains, curves its way out through the last foothills of the Caucasus Mountains into the endless expanse of the plains to their north. There, scattered in confusion after their high-altitude drop and still searching in vain for their supplies and equipment, they were attacked by elements of a group of around 400 Soviet militiamen and 2,000 NKVD troops.

Having succeeded in breaking contact with the enemy they immediately withdrew up the Argun River to a settlement marked as "Barsoi" on the German map. [Judging by the map's scale, however, and considering the fact that the settlement of "Dachu-Barzoi" still stands to this day barely a few kilometres to the south of Duba-Yurt, the map's author almost certainly meant the village of Shatoi, half-way between Duba-Yurt and Itum-Kale.]

According to the map, over the next 19 days and with Soviet units and machine-gun nests in hot pursuit, the men of Operation Shamil progressively fell back up the Argun Valley, arriving in "Barsoi"/Shatoi on the 13th of September. From there they did a loop to a place called "Oschnoi" a few days' march to the south-west—probably in an attempt to contact Chechens sympathetic to their anti-Soviet cause.

The unit travelled via a settlement called "Derschkhoi" two days' march to the west of "Barsoi"/Shatoi, where they spent the night of the 15th, and arrived in "Oschnoi" on the 18th. Here they seem to have been attacked by Soviet forces advancing from the north-west, and the men were perhaps forced to beat a hasty retreat. In any case, they returned to "Barsoi"/Shatoi almost immediately, arriving there after two days' march on the 22nd.

In both "Barsoi"/Shatoi and "Oschnoi", the Brandenburgers apparently made contact with two Chechen resistance organizations, whose members, according to the report, were more than willing to fight the Soviets if the Germans would give them the weapons, supplies and equipment they would need. (The approximate position and estimated strength of these groups is indicated by gray circles on the map.)

The Brandenburgers spent two nights in "Barsoi"/Shatoi, where they were probably still in touch with Chechen freedom fighters, but the map of their route next mentions a fire-fight in a place called Khersennoi, a few kilometres to the west, which took place on either the 24th or the 25th of September. During this fire-fight the Brandenburgers apparently succeeded in breaking contact with the enemy but became separated from their Chechen sympathizers, for their route over the following days is marked 'ohne führer', 'without a guide'.

For the next six days, the Brandenburgers' route took them through the rugged, thick forests of the northern foothills of the Caucasus. They veered north, making their way down a valley for three days before crossing into the next valley to the west and heading back up towards the mountains for a day; they then resumed their westwards push towards the closest German units, whose advance had stalled many kilometres distant. Perhaps this detour was an attempt to evade the battalion of Soviet troops which was to try to encircle them in the forest a few days later.

The words 'ohne führer' stop on the 1st and 2nd of October. Having now perhaps once again found a Chechen sympathizer willing to guide them through the forest, the men of Operation Shamil spent the next 14 days successfully evading the attempts of an entire battalion of Soviet units to find and capture them, a threat which reportedly ended on or around the 17th.

After marking what seems to have been a brief halt somewhere in the never-ending forests, the Brandenburgers continued their weary march towards allied position to their north-west. Arriving on the 18th of October in the village of Galashki (perhaps; the map is throughout unclear) around 60 kilometres to the west of "Barsoi"/Shatoi, they headed north towards the village of Surkhakhi, which they reached on the 22nd.

No doubt desperately in need of a rest from the constant fighting and the difficult march through the forest, the Brandenburgers apparently spent a week just to the south-east of Surkhakhi before resuming their march on the 1st of November. The difficult conditions behind enemy lines and the threat of winter were now compounded by the arrival of 'strong enemy forces' in Surkhakhi, where the Brandenburgers reportedly ambushed a column of enemy vehicles.

Having once again managed to evade encirclement and capture, the Germans holed themselves up in the neighbouring village of Ekazhevo, a mere 6 kilometres to the west. The map claims they spent 3 nights in Ekazhevo—time which they perhaps needed to figure out a way of crossing the Sunzha River and bypassing the important town of Nazran.

They apparently crossed the Sunzha and the important Nazran-Ordzhonikidzevskaya railway line by Barsuki, a village 7 kilometres to the north of Nazran. The map, however, indicates that the Brandenburgers' presence was detected during this twin crossing: threatened with another Soviet attempt to encircle and destroy them (it was to be the last), the men of Operation Shamil once again managed to fight their way out in a north-westerly direction and resumed their long march to allied lines.

On the 18th of November, the map indicates that the men of Operation Shamil had reached the village of "Nishne-Atschaluki", having cautiously advanced 16 kilometres in three days through the endless fields which separate Barsuki from Akhalukhi. Here, after a short halt (18-20 November), the Brandenburgers turned due west. It took them another three weeks in six stages to finally reach the closest German positions in Verkhniy-Kurp, a mere 30 kilometres away.

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2015

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb