JOHANN ANTON GÜLDENSTÄDT'S

R e i s e n

durch

R u ß l a n d

und im Caucasischen Gebürge

The two volumes of Johann Anton Güldenstädt's Reisen durch Rußland und im Caucasischen Gebürge ["Travels through Russia and in the Mountains of the Caucasus"] were published posthumously by Peter Simon Pallas between 1787 and 1791. An updated, re-edited version of his Reisen was also published by Julius Klaproth in the "Verlage der Stuhrschen Buchhandlung" in 1834, under the title Dr. J.A. Güldenstädts Beschreibung der kaukasischen Länder—Aus seinen Papieren gänzlich umgearbeitet, verbessert herausgegeben und mit erklärenden Anmerkungen begleitet von Julius Klaproth. All are available on the Internet Archive website.

Regrettably, I have no reference books here in Georgia which could provide me with a biography—however short—of Johann Güldenstädt, and since most of the biographical material on the internet seems to be recycled from the Wikipedia entry on him, I shall quote freely from the latter source.

JOHANN ANTON GÜLDENSTÄDT was a Baltic German naturalist and explorer, whose career was largely built in the service of the Russian empire. Born in 1745 in Riga (now the capital of Latvia—then, part of Imperial Russia), he studied at the University of Frankfurt, obtaining his doctorate in medicine in 1767 at the tender age of 22.

The following year he joined the St. Petersburg (i.e. Imperial Russian) Academy of Science's expedition sent by empress Catherine II ("The Great") to explore the empire's southern borders. Güldenstädt travelled through the Ukraine and the Astrakhan region to the northern Caucasus and Georgia—both of which were quasi terra incognita at the imperial court and almost entirely beyond the borders of the Russian empire—returning to St. Petersburg in 1775.

Güldenstädt's expedition was the first systematic study of the Caucasus. As was typical of contemporary expeditions organized in the spirit of the Enlightenment, it was tasked with the observation and description of virtually every aspect of the region under study, sparing readers no detail, however insignificant. This included both its "natural" attributes—flora, fauna, geography, geology, topography, &c. &c.—and every aspect of the region's peoples, economies, and governments. In this sense it was both a scientific expedition and a mission of reconnaissance to learn more about a region that was important to the simultaneous [first] Russian war against the Ottomans (1768-1774), of which the Caucasus was a theater, with the Georgians acting as Russian allies.

Immediately following the expedition, Russian interest in the region—and particularly Russian interest in Georgia—grew markedly, culminating in the Treaty of Georgievsk, which made East Georgia a Russian protectorate, and which marked the beginning of the end for Georgia's independence and sovereignty.

The expedition also contributed greatly to the fields of biology, geology, geography, and particularly linguistics. Güldenstädt took detailed notes on the languages of the region, and compiled comparative word-lists for Georgian, Mingrelian, Svan, Persian, Kurdish, "Kazak-Tatar", Ossetian (Digoron), Kabard, "Abassish", Andi, Ghazi-Ghumukh, Lezgian, Dido, Khunzakh, &c. &c.

After the expedition, which definitively established Güldenstädt's reputation at the Academy, he continued to work as a naturalist. During his expedition to the Caucasus, he "collected" (i.e. shot—binoculars were not yet very advanced at that time) several species of bird which are named after him—most notably "Güldenstädt's Redstart" (Phoenicurus erythrogaster).

Güldenstädt died from an outbreak of fever in St. Petersburg in 1781, aged only 36.

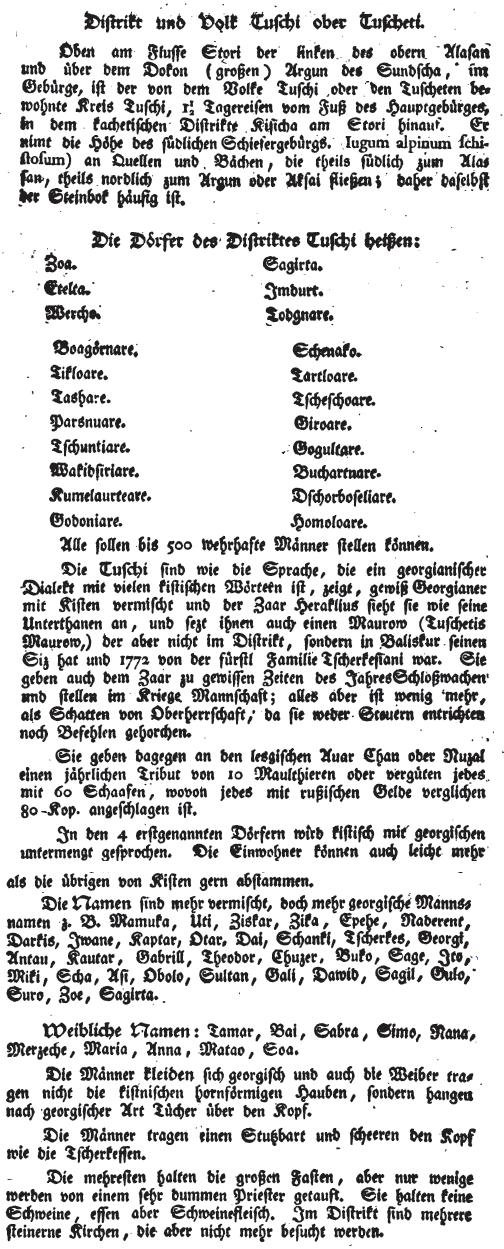

Güldenstädt's Reisen is of interest not only for its detailed account of the Caucasus region in the XVIIIth century, however, but also because the author was (I believe) the first scientist and academic to mention the Bats people, who thus make their first historiographical appearance in its pages! Here is a scan of Güldenstädt's entry on the Tush and Tusheti (pp. 376-378 of Vol. I of G.'s Reisen) , followed by my (approximate, but near-complete) transcription of the book's gothic typeface:

Distrikt und Volk Tuschi oder Tuscheti

Oben am Flusse Stori der linken des obern Alasan und über dem Dokon (großen) Argun des Sundscha, [? im] Gebürge, ist der von dem Volke Tuschi oder den Tuscheten bewohnte Kreis Tuschi, 1½ Tagereisen vom Fuß des Hauptgebürges, in dem kachetischen Distrikte Kisicha am Stori hinauf. Er [? nimt] die Höhe des südlichen Schiefergebürgs. (Iugum alpinum schistosum) an Quellen und Bächen, die theils südlich zum Alassan, theils nordlich zum Argun oder [? Aksai] fließen; daher daselbst der [? Steinbok] häufig ist.

Die Dörfer des Distriktes Tuschi heißen:

Zoa. [probably "Tsova", i.e. "Tsaro"] - Sagirta.

Etelta. - Imdurt. ["Indurta"]

Wercha. ["Verkhovani"?] - Todgnare. [?]

Boagdrnare. [?] - Schenako.

Tikloare. ["Diklo"] - Tartloare. ["Dartlo"]

Taschare. - Tscheschoare. ["Tchesho"]

Parsnuare. ["Parsma"] - Giroare. ["Girevi"]

Tschuntiare. ["Chontio"] - Gogultare. ["Goglurta"]

Wakidsiriare. ["Vakisdziri"] - Buchartnare. ["Bukhurta"]

Kumelaurteare. ["Kumelaurta"] - Dschorboseliare. ["Djvarboseli"]

Godoniare. ["Gudanta"] - Homoloare. ["Omalo"]

Alle sollen bis 500 wehrhafte Männer stellen können.

Die Tuschi sind wie die Sprache, die ein georgianischer Dialekt mit vielen kistischen Wörtern ist, zeigt, gewiß Georgianer mit Kisten vermischt und der Zaar Heraklius sieht sie wie seine Unterthanen an, und sezt ihnen auch einen Maurow (Tuschetis Maurow,) der aber nicht im Distrikt, sondern in [? Baliskur] seinen Siz hat und 1772 von der fürstl Familie Tscherkessiani war. Sie geben auch dem Zaar zu gewissen Zeiten des Jahres Schloßwachen und stellen im Kriege Mannschaft; alles aber ist wenig mehr, als Schatten von Oberherrschaft; da sie weder Steuern [? entrichten] noch Befehlen [? gehorchen].

Sie geben dagegen an den lesgischen Auar Chan oder Nuzal einen jährlichen Tribut von 10 Maulthieren oder [? vergüten jedes] mit 60 Schaafen, wovon jedes mit rußischen Gelde verglichen 80 Kop. angeschlagen ist.

In den 4 erstgennanten Dörfern wird kistisch mit georgischen untermengt gesprochen. Die Einwohner können auch leicht mehr als die übrigen von Kisten gern abstammen.

Die Namen sind mehr vermischt, doch mehr georgische [? Mannsnamen] z.B. Mamuka, Uti, Ziskar, Zika, Epehe, [? Naderent], [?Darkis], Iwane, [? Kaptar], Otar, Dai, Schanki, Tscherkes, Georgi, Antau, Kautar, Gabrill, Theodor, Chuzer, [? Buko], Sage, Ito, [? Miki], Scha, [? Asi], Obolo, Sultan, Gagil, Dawid, Sagil, Gulo, Suro, Zoe, Sagirta.

Weibliche Namen: Tamar, Bai, Sabra, [? Simo], Nana, Merzeche, Maria, Anna, Matao, Soa.

Die Männer kleiden sich georgisch und auch die Weiber tragen nicht die kistinischen hornförmigen Hauben, sondern hangen nach georgischer Art Tücher über den Kopf.

Die Männer tragen einen Stutzbart und scheeren den Kopf wie die Tscherkessen.

Die mehresten halten die großen Fasten, aber nur wenige werden von einem sehr dummen Priester getauft. Sie halten keine Schweine, essen aber Schweinefleisch. Im Distrikt sind mehrere steinerne Kirchen, die aber nicht mehr besucht werden.

The District and People of Tushi or Tusheti

Up by the Stori River the left [? branch] of the upper Alazani [River] and over the Dokon (big) Argun of the Sundzha, in the mountains, lies the area called Tushi, inhabited by the Tushi or Tushetian people, 1½ days' journey from the foot of the main mountain range, in the Kakhetian district of Qiziqi up the Stori [River]. It [Tusheti] [? occupies] the heights of the southern range of the schistous mountains. iugum alpinum schistotum at springs and streams, which flow partly southwards to the Alazani [River], partly northwards to the Argun or [? Aksai] [Rivers]; thus [where] the [? ibex] is numerous.

The villages of the District of Tushi are called:

Zoa. [probably "Tsova", i.e. "Tsaro"] - Sagirta.

Etelta. - Imdurt. ["Indurta"]

Wercha. ["Verkhovani"?] - Todgnare. [?]

Boagdrnare. [?] - Schenako.

Tikloare. ["Diklo"] - Tartloare. ["Dartlo"]

Taschare. - Tscheschoare. ["Tchesho"]

Parsnuare. ["Parsma"] - Giroare. ["Girevi"]

Tschuntiare. ["Chontio"] - Gogultare. ["Goglurta"]

Wakidsiriare. ["Vakisdziri"] - Buchartnare. ["Bukhurta"]

Kumelaurteare. ["Kumelaurta"] - Dschorboseliare. ["Djvarboseli"]

Godoniare. ["Gudanta"] - Homoloare. ["Omalo"]

All [are said] to [be able to] provide 500 armed men.

The Tushi are—as the language, which is a dialect of Georgian with many Kist words, shows—certainly Georgians mixed with Kists, and [King Erekle] considers them his subjects, and attributes them a [mouravi, i.e. lord] ([in Georgian:] tushetis mouravi), who however does not have his seat in the district, [sitting instead] in [? Baliskur] and [who] in 1772 was from the ducal family of Tcherkessiani. They [the Tush] also provide the King with palace guards at certain times of the year, and provide men during wars; all this, however, is little more than a shadow of overlordship, since they neither pay taxes nor obey commands.

In addition to this, they pay a yearly tribute to the Lesghian Avar Khan or Nutzal of 10 mules or compensate the same with 60 sheep, [the value of] each one of which is set at 80 kopeks of Russian money.

Kistian and Georgian are spoken equally in the 4 first-named villages. [Their] inhabitants could also more easily be descendants of the Kists [than the other Tush].

The names are more mixed, [although] there are more Georgian men's names, for example Mamuka, Uti, Ziskar, Zika, Epehe, [? Naderent], [?Darkis], Iwane, [? Kaptar], Otar, Dai, Schanki, Tscherkes, Georgi, Antau, Kautar, Gabrill, Theodor, Chuzer, [? Buko], Sage, Ito, [? Miki], Scha, [? Asi], Obolo, Sultan, Gagil, Dawid, Sagil, Gulo, Suro, Zoe, Sagirta.

Female names: Tamar, Bai, Sabra, [? Simo], Nana, Merzeche, Maria, Anna, Matao, Soa.

The men clothe themselves in the Georgian style and the women, too, do not wear the horn-shaped Kistian headdresses, instead hanging [scarves, lit. cloths] over the head according to the Georgian style.

The men [have] tile-beards and shave their heads like the Cherkessians.

Most hold the important fasts, but only a few of them are baptised by a very imbecile priest. They do not keep pigs, yet eat pork. Several stone churches are [to be found] in the district, which are however no longer visited.

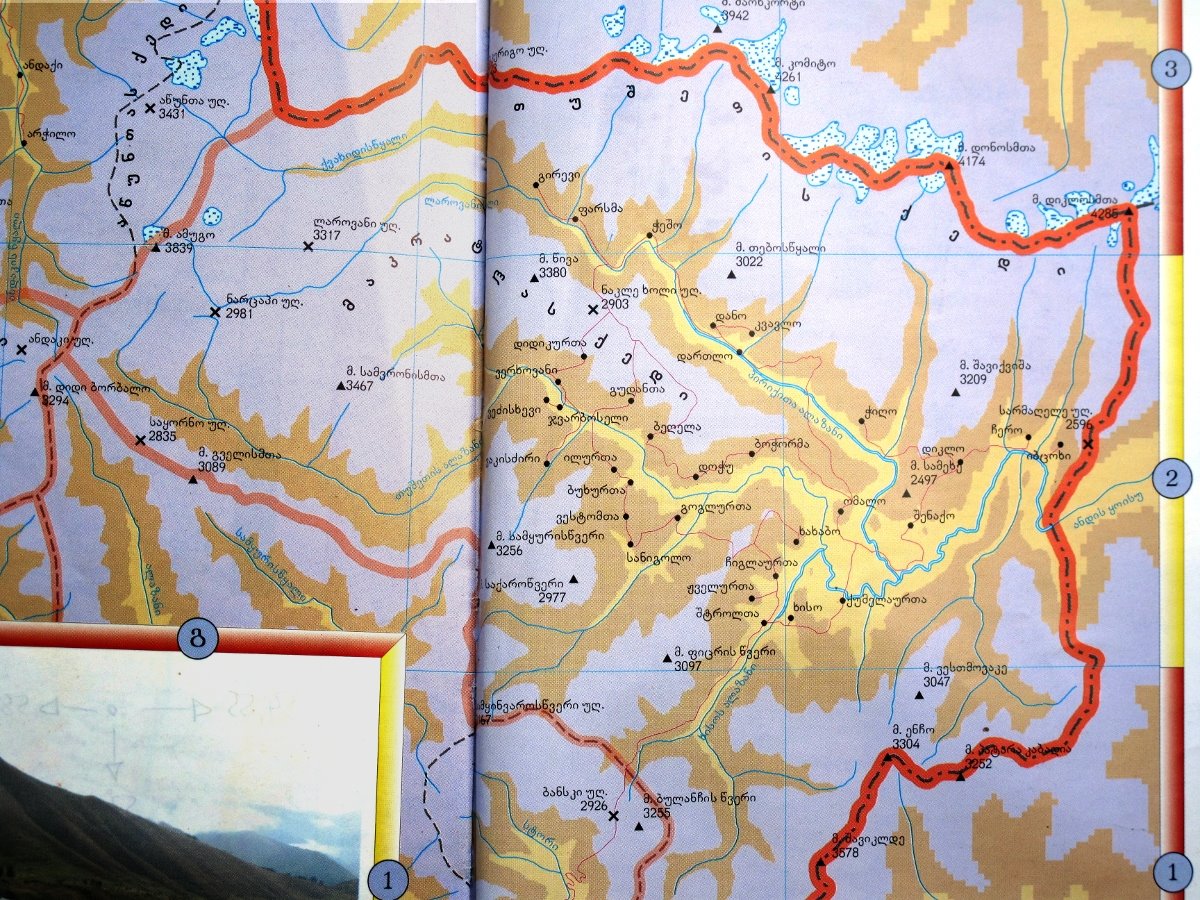

Note: Two of the place-names—"Todgnare", "Boagdrnare"—in Güldenstädt's account of Tusheti elude me; they do not seem to relate to any existing toponyms. For purposes of comparison, I am using the best material I can find, viz. a 1:250,000 atlas published in Georgia in 2006. (Please click on the image below for a closer look at Tusheti copied from the relevant page of this atlas; the map is © GeoAnalytica 2006)

Another noteworthy curiosity regarding the place-names in Güldenstädt's account: Prof. Topshishvili (whose article on the Batsbi/Tsova Tush I have published in its entirety on this website) remarks upon the fact that the suffix "-are", which is no longer in use nowadays, is of Vainkah origin. In his words:

By the way, as it is quite obvious, information [regarding the names of the villages of Tusheti—AB] is obtained by the German scientist from the Tsova-Tushs (the Batsbs). It is approved by the names of the villages: "Diklo-Arre", "Dochu-Arre". The Tsova-Tushs called the Diklos, the Shenakos like this, which means the inhabitants of Diklo and Shenako (the Diklos, the Shenakos).

This might also explain the fact that the first four villages in Güldenstädt's list are the four main [or remaining] villages of Tsovata. Only a Batsav would have namd his villages first! (And should a traveller follow Güldenstädt's indications and journey up the Stori River to Tusheti i.e. along the main "road", the first village mentioned in Güldenstädt's list he would encounter would be Kumelaurta.)

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2010

Gmail: alexjtb