W A S T Y R D J Y

OR

ST GEORGE

AMONG THE OSSETIANS

—

Notes on the Pagan Festival of St George in North Ossetia

by Robert Chenciner, 19-26 November, 1991

In February 2008, I received an email, all the more welcome for being unexpected, from Mr Robert Chenciner—self-proclaimed "Eastern Caucasologist" and author of several books on the Caucasus, most notably Daghestan: Tradition and Survival, Tattooed Mountain Women and Spoon Boxes of Daghestan and Madder Red (see the bibliography on this website for details and other publications).

In his email, Chenciner suggested I publish the following article on the rituals surrounding Wastyrdjy, the feast of St George as celebrated by the Ossetians. This text is his, carefully edited where appropriate.

Contents:

1. Background to Robert Chenciner's Visit to North Ossetia—2. Introduction—3. North Ossetia—4. The Ossetian St George, by Anna Chaudhri—5. "Djiorguba" or "Wastyrdjy", the Festival of St George—a. Four Feasts—b. The Prayer before the Sacrifice—c. Feast Structure and Customs—d. Nine Obligatory Toasts—e. Three Additional Toasts—f. Songs—g. A Miracle Reported in 1992—6. The National Pagan Shrines—a. The Three Shrines at Rekom—b. "Tbao-Wasilla", the Shrine of St Wasilla—c. "Dzvgisy dzuar", the Shrine of St George—7. The Ceremonies held at the Shrine of St George—a. The Priest's Blessing of Festival Offerings of Food and Drink—b. The Priest's Blessing of Those Present with a Hearth-Chain—8. Epilogue: A Sacred Bull's Horn from Rekom—Appenda—1. Luidmilla Holt's Transcription and Translation of the First Feast—2. Songs about St George—3. Further Questions

1. Background to visit

[I] was invited to visit North Ossetia by Dr Hasan Dzutsev, then 45, a senior local sociologist. As a rare foreigner, [I] was generously given every access to study the pagan festival of St George. [I] stayed with Dr Dzutsev, his wife Sveta, a doctor, and their two boys Amiran, 14, and Akhmad, 12, who were both learning English. They lived in an apartment on the 12th floor of a sixteen-storey tower block, surprisingly built only five years before, at No 12 Tsokolaeva Street in a suburb of Vladikavkaz, the capital of North Ossetia, in a new micro-district accommodating 37,000 people. The Dzutsev's four-room flat had two glazed balconies, which overlooked a breathtaking panorama of the main chain of the Great Caucasian mountains, crowned by mount Elbrus in the distance. The initial introductions had been arranged by our mutual sociologist-ethnographer colleague Dr Magomedkhan Magomedkhanov of the Daghestan Scientific Center, part of the USSR (now Russian) Academy of Sciences. Dr Dzutsev, who was an early pioneer of attitude surveys in the USSR, also made a return visit to London.

2. Introduction

[I] tape-recorded the ceremonies and prayers in the ancient Digoron dialect of Ossetic, as well as conversations in the more commonly-spoken Iron dialect. [My] hosts Sveta and Hasan Dzutsev had the daunting task of transcribing and translating some of them into Russian during Chenciner's stay. Back in Cambridge, Ossetic linguist and specialist Dr Anna Chaudhri (née Butler) transcribed and translated one of them—the Prayer before Sacrifice—and made background notes, which are included below. Sadly she was unable to finish the project, though we presented an illustrated talk at the Ancient India and Iran Trust in Cambridge. The baton was partly taken up by Luidmilla Holt, an Ossete married to an Englishman who lives in Sheffield. She splendidly helped with transcription and translation of an entire side of a 90-minute tape, mainly in Iron, of the first feast in Vladikavkaz on 20th November, in addition to providing some useful explanatory notes and comments.

I regret that I have waited for over 16 years to publish this, apart from an interview by Louisa Young in the London Times on St George's Day in 1992. As no further material has appeared, I think that it is better to publish what there is—my ethnographic account with the available translations, along with some of my step-by-step accompanying pictures of the feasts, ceremonies and shrines. There are also a few pictures of objects and additional old pictures which I was allowed to take in the (then) Leningrad Ethnographic Museum (now the Russian Ethnographic Museum), mainly from the collection of V. F. Miller, the pre-eminent 19th century Ossetic scholar.

3. North Ossetia

North Ossetia is a small Autonomous Republic in the Russian Federation. North Ossetians make up just over half the population of 643,000, with 35% Russians and 5% Ingush, the other main ethnic groups. (These figures are from the 1991 census.) There are also Ukranians, Armenians, Georgians and Jews. Since 1990, 80,000 South Ossetian refugees—fleeing what they report as racist oppression in Georgia—have settled near the capital, Vladikavkaz, where about 300,000 people usually live. The Ingush claim half of Vladikavkaz as theirs, because it was part of their territory up to when they were forcibly transported to Central Asia by Stalin in 1944, and they have started terrorist acts against the Ossetes. (Stalin accused them—and the related Chechens—of cooperating with the Nazis, who reached the suburbs of Grozny in 1943 before being pushed back.) One result of these terrorist acts is that buses have stopped running between Vladikavkaz and Grozny, the capital of what was recently the autonomous republic of Chechnya-Ingushetia. By tradition, North Ossetia is divided into 8 "usheli", or regions, centered upon river valleys bounded by the northern flank of the Caucasus mountains.

North Ossetia is a small Autonomous Republic in the Russian Federation. North Ossetians make up just over half the population of 643,000, with 35% Russians and 5% Ingush, the other main ethnic groups. (These figures are from the 1991 census.) There are also Ukranians, Armenians, Georgians and Jews. Since 1990, 80,000 South Ossetian refugees—fleeing what they report as racist oppression in Georgia—have settled near the capital, Vladikavkaz, where about 300,000 people usually live. The Ingush claim half of Vladikavkaz as theirs, because it was part of their territory up to when they were forcibly transported to Central Asia by Stalin in 1944, and they have started terrorist acts against the Ossetes. (Stalin accused them—and the related Chechens—of cooperating with the Nazis, who reached the suburbs of Grozny in 1943 before being pushed back.) One result of these terrorist acts is that buses have stopped running between Vladikavkaz and Grozny, the capital of what was recently the autonomous republic of Chechnya-Ingushetia. By tradition, North Ossetia is divided into 8 "usheli", or regions, centered upon river valleys bounded by the northern flank of the Caucasus mountains.

4. The Ossetian St George, by Anna Chaudhri

The name of St George in Ossetic is "Wastyrdjy" in Iron, "Wasgergi" in Digoron. According to Prof. Vasily Abaev, the great philologist (1900-2001), the Ossetic forms of the saint's name are closest to the Mingrelian (Western Georgian) forms of the name of George, i.e. Gerge, Dzherge. The Ossetic word "Wac" which occurs in several saints' names in Ossetic is a word of old Iranian origin, meaning 'spirit", "deity", "saint'. The festival called "Djiorguba" (from the Georgian "Giorgoba", "the day of St George") is the annual feast of St George held in November. The Ossetic month of November is named after this festival: "Djiorgubaj mäj" ("the month of Djiorguba").

Wastyrdjy is perhaps the most popular of all the Ossetian saints ("dzuar", from the Georgian "djvar", "cross"). He is the patron of men and masculine activity such as war and raiding. He is also the protector of all travelers. Shrines to Wastyrdjy are to be found all over Ossetia and there are other minor festivals held in his honour at these shrines at other times of the year. (November is the main feast however.) Traditionally women were excluded from the rites of Wastyrdjy. They referred to him as "lägty dzuar" ("saint of men") because his name was a taboo for them.

Wastyrdjy was portrayed as a dazzling armed knight, clad in a white burka [archaic hairy felt full-length cloak, used throughout the Caucasus] and riding about on a white, three-legged horse. He is particularly concerned with human affairs, and was thought to appear frequently among men in various guises. In the Nart legends he sometimes plays a role: According to one Ossetian tradition, he is said to be the father of the greatest Nart heroine Satana. This legend is a rather disreputable one from the saint's point of view, and it illustrates how dangerous to women he can be: Wastyrdjy pursues Satana's mother unsuccessfully during her lifetime and so when she dies, he visits her in her grave on the third night after her death and has intercourse with her corpse, from which union Satana is born. Wastyrdjy also lets his horse and hunting hound have intercourse with the dead woman and from these unions the greatest horse and the chief dog of the Narts are born.

Wastyrdjy was revered among the mediaeval ancestors of the Ossetes. He clearly combines features of some pre-Christian deity with those of the Christian saint. Christianity first came to the ancestors of the Ossetes via the Georgians in the 5th and 6th centuries. However, with the Mongol invasion at the end of the 13th century came a strong revival of the old pagan cults, the gods of the old pantheon, and the conversion (or re-conversion) of many churches into pagan shrines. The second wave of conversion to Christianity came from Russia in the 18th century. Ossetian Christianity is characterized by some unique and archaic traits [many of which it shares in common with most forms of Christianity as practised by the mountain tribes of the Caucasus, such as the Svans, Khevsurs, Pshavs, Tush, &c.—A.B.]

Wastyrdjy is sometimes assigned other, lesser features. He is sometimes thought of as a patron of the poor, and farmers sometimes pray to him for an abundant crop and for fertility among their domestic animals. Three of the important shrines dedicated to Wastyrdjy are Rekom, Dzvgisy dzuar and Styr Xoxy dzuar.

5. "Djiorguba" or "Wastyrdjy", the Festival of St George

—Robert Chenciner (taken during the second fest, 4th from left, holding a drinking-horn)

a. Four Feasts

In Daghestan, whose people I have studied since 1985, I have found that old traditions survive in villages and are often modified or lost in towns. However, Vladikavkaz disproved this. On my first morning, I was surprised to look down from our twelfth-floor balcony and see a vast 300-litre pot bubbling away on a welded steel tube trivet, surrounded by a golden-flamed fire. Peering through the white swirling steam, the (male) cooks fished out large chunks of a four year-old bull on the boil. It would take nearly three hours to cook. Next to it stood a smaller 50-litre vat with the intestines and other choice innards. The bull had cost 2,500 rubles—not expensive compared to those we saw later. I refused the offered glass of "buza", an intoxicating beer-like drink, the local recipe of which is described later. Next to the outdoor kitchen was a long single-storey hut, built by popular subscription to accommodate feasts. Inside, three long tables were being laid under silver decorations, to feed over three hundred revellers. Far from being secret, 39 pagan festivals were announced on the popular Iron dialect Ossetian calendar for 1991.

—Bull on the boil

The price of sacrificial rams and bulls reflected current hyperinflation. On the outskirts of Vladikavkaz, shepherds had gathered flocks of rams. Townspeople drove up in their cars. A couple of men would select a ram (weighing about 20kg), bargain and agree upon a price of 500 to 700 rubles, and then lead their sacrificial ram away. If it was frisky, they bound its front and rear feet together, and the ram was then carried across the road and put in the their car's boot, an undignified start to its last journey… Bulls weighing 600kg were led onto trucks at the livestock market, where rams, pigs, piglets and riding horses were also for sale. Bull meat cost about 18 rubles a kilogramme, and meat weight was valued at about half the cost of its live-weight. Two years ago [in 1989] a bull cost 800 rubles; last year the price had increased to 1,500, and this year a bull cost 7,000 rubles, reflecting the free-fall of the currency. There was a stir in the market as a mountaineer from South Ossetia led in his pair of shiny black bulls. 'I crossed two passes and walked for nine days to bring them here. He is nine and he is seven years old. I want 8,000 and 6,500 rubles. Sure, they lost a little weight on the journey. Look, do you want to buy them or not?' I took his picture instead. The best bulls were three years old. The older they were, the longer they took to cook.

—'I crossed two passes and walked for nine days to bring them here.'

For the record, I attended four of the seven ritual feasts, which were essentially similar to each other, and the Sunday rituals at the main shrine of St George, Dzvgisy dzuar.

The first feast on 20 November was held in the tower-block where Hasan and his family lived in Vladikavkaz. Trafim Kulaev's flat was on the third floor. When we arrived, the funeral of an Ossetian police officer killed by Ingush while guarding a water reservoir was on television. He had been shot 28 times. In one of the many addresses, a colonel broke down in tears. We stood in respect as the mustachioed corpse was carried and set down in his open coffin. Fiodor Khabilov, the Elder in charge of the evening's proceedings, accordingly gave our feast a political slant. He was said to sing beautifully, but he stopped when his brother died two months before. On his left sat the oldest man present, the Elder, an unusually cadaverous-looking Zelim Karaev, who spoke Digiron, and who had been the Elder in previous years. Next to me sat a more typically solid older man, Khamatkhan Urtaev. These three are most audible on the recording of the meal, transcribed and translated by Luidmilla Holt below. There were 14 men around the table, including two who arrived late. Kazbek Karaev was the youngest at about thirty.

—The sacrificed bull's head presented on the festival table

The second feast on 21 November was held in Beslan—population 70,000—where the through-train stops for Vladikavkaz, about half an hour's drive away. Sveta's aunt Ashak's family house was in a built-up rural area, beside a dirt road. On the table was a bull's head, reflecting the relative wealth of this family. As a special exception, because I was there, three women sat at the junior end of the table. They quickly became bored with the endless toasts. The table's Elder was Kazbek Bitaevi, and I sat on his right. Opposite, Korman Kusev, a businessman, said that these customs had been described by Homer. Zig-zagging down the table, Isapek Dzgoev sat on my right, opposite Grigori Kasaev, across from Hasan, who faced Frier Baterbekov. Next to Hasan sat Aslan Khadikov, a gigantic ruddy-faced farmer, and opposite him Murat Gusev. At the far end Zamakal Kusev was the youngest, whose place had been given by his father Ziu, Ashak's husband, who was technically our host.

—Kazbek Bitaevi being offered the plate of intestines (a delicacy)

After a night off, on 23 November I saw a ram sacrificed for the third feast on the outskirts of Zamankul village, at the large house of another of Sveta's aunts, 75 year-old Gugla Dezoyeva. She has lived there on her own since her husband died eight years ago. The piped water with a frost-proof siphon and the stoves in each of the three brothers' first-floor rooms bore witness to the family's prosperity and enthusiasm for technology. Zadbek, the oldest son, is rich; above the village, he proudly showed us an elegantly-landscaped dam project, which he is constructing around a mineral spring, both to bottle and sell the tasty water. In addition, the reservoirs will prevent the village from being flooded and from the consequent bog mosquitoes. The middle brother, the rounded Murat, was the sacrificer and singer.

The following afternoon, on 24 November, we feasted at Hasan's friend Gerzhen Uruzhov, 53, in his Alagir town house. His brother Makhar, at 38, was manager of one of the largest factories, with 3,000 employees. He glowed with success, speaking in a witty staccato. They both answered some of my questions arising from the previous feasts.

The quoted prayers and blessings which follow are my rough English translations of Russian translations done by Amiran, Hasan's son, of Ossetic transcriptions by Sveta, Hasan's wife, with a little help from Hasan. When we returned home after one feast at about half past nine, with Hasan fading, Sveta complained about the television, the tea burning, flies buzzing, me washing my face with cold water, and another time, that a girl friend's mother had died. Ignoring all these excuses, I worked the tape recorder backwards and forwards until she transcribed these texts. She was better at speaking Iron that Hasan. It took them till three in the morning on my last night.

b. The Prayer before the Sacrifice

This blessing was held outside the family home in Zamankul, a Muslim rather than Christian pagan village, in the Pravoberezhnii region (meaning right-hand river bank, currently claimed by the Ingush). A group of family men and boys gather before drinking a toast of home-brew distilled corn liquor and sacrificing a bull or ram for each of the seven evening feasts. The sacrificer, Murat Dzgoev, 38, said the following blessing, which Hasan and the others present considered to be both fine and full. It was later also transcribed and translated by Dr Anna Chaudhri, and serves as a good example of archaic Digoron language. (The local translation compared closely but not exactly with Dr Chaudhri's academically accurate translation.)

Styr Xuycawy xorzäx nä wäd!

'May the mercy of the Great God be ours!'

[1] Kädtäridtär nyn äxxuysgänäg kuyd wa, ucy amond nä wäd!

'May that fortune be ours, (namely) that He will always be our helper!'

[2] Bärägbon u ämä afädzäj-afädzmä dombajdär kuyd cäwa, ucy amond nä wäd!

'It is the feast day and may such fortune be ours, that from year to year this feast day will become greater!"

[3] Wastyrdzhijy bontä styr ämä dombaj kusart či akodta, max där wyj ämbal kuyd wäm, axäm amond nä wäd!

'May such fortune be ours, that we too may be the companion of him who has made a great and mighty sacrifice during the days of St George!'

[4] Binontä stäm ämä dombajdär binontä či fäcis, styr bärzond Xuycaw xuyzdär xärztä kämän rakodta, max binontä där wydony ämbal kuyd woj, axäm xorzäx nä wäd!

'We are a household and let such an indulgence be ours, that our household too may become the companion of those who have become the most powerful household, to whom the great, high God has given the best blessings!'

[5] Wädä nyn syxbästä is ämä ucy syxbästimä dombajä, fidaräj kuyd cäräm, ucy amond nä wäd!

'Thus we have neighbours and may such fortune be ours, (namely) that we may live strongly and robustly with those neighbours!'

[6] Na xistärtä amonddzhyn.qäldzägäj sä kästärty cindzinadäj äfsäst kuyd woj!

'May our elders be fortunately and joyfully sated with the joy of their younger ones!'

[7] Bärägbon u ämä nä xistärtän Xuycaw axäm aqaz bakänäd ämä sä kästärtä fyldäräj-fyldär kuyd känoj, amonddzhynäj-amonddzhyndär kuyd känoj, wucy amond nä wäd!

'It is the feast day and may such fortune be ours, that God may lend such support to our elders that their younger ones may increase and increase [in number], and that they may grow more and more fortunate!'

[8] Wädä afädzäj-afädzmä styr kusärdtä fäkänäm, dombaj kusärdtä fäkänäm ämä acy kusart där Xuycaw jäximä kuyd ajsa, axäm amond nä wäd. Wastyrdzhi nyn käddäridtär äxxuysgänäg kuyd wa, axäm xorzäx nä wäd!

'Thus from year to year we make great sacrifices, we make mighty sacrifices, and may such fortune be ours that God may [accept this our sacrifice to Him]. May such an indulgence be ours, that St George may always be our helper!'

[9] Zädtä birä sty, birä adäm säm fäkuyvtoj. Nä fydältän birä xorzdzinad lävärdtoj ämä maxän där xorzdzinad kuyd dättoj, ucy amond nä wäd!

'The angels are many, and many people have prayed to them. They have granted much grace to our fathers, and may such fortune be ours that they may grant grace to us too!'

[10] Xoxäj bydyrmä či zädtä is, wydon nyn käddäridtär äxxuysgänäg kuyd woj, axäm amond nä wäd!

'May such fortune be ours that, whichever angels there are from the mountains to the plain, they may always be our helpers!'

[11] Tätärtup nä särty gäsäg u ämä nyn nä wäng rog ämä dombaj kuyd käna, ucy amond nä wäd!

'Tätärtup is [?the] one who watches over us, and may such fortune be ours that he may make our limb(s) swift and strong!' ["Tätärtup" is the name of a village, but here the word probably refers to "Tutyr", a deity, the patron of wolves, and so here perhaps means: 'Keep our flocks safe from wolves'!]

[12] Mykalgabyrtä zäxxy bynty cäwäg sty ämä nyn nä k'axfäd käddäridtär dombaj kuyd känoj, axäm amond nä wäd!

'[The Archangels] Michael and Gabriel are walking beneath the Earth [?below ground] and may such fortune be ours, that they make our footsteps always strong!'

[13] Wädä xäxty dzuartä käddäridtär nyn äxxuysgänäg kuyd woj, ucy amond nä wäd!

'Thus may that fortune be ours, (namely) that the saints of the mountains may always be our helpers!'

[14] Bydyry zädtä läwwäg kuyd woj, ucy amond nä wäd!

'May that fortune be ours, (namely) that the angels of the plain may serve (us)!'

[15] Wädä bärkaddzhyn kuyd wäm käddäridtär, ucy amond nä wäd!

'Thus may that fortune be ours, (namely) that we may always be productive!'

[16] Dune sabyr kuyd wa, zäxxy k'orijy adäm sä kärädzijy kuyd warzoj, ucy amond nä wäd!

'May that fortune be ours, (namely) that the world may be peaceful, that the people of the Earth may love each other!'

[17] Nä bärkädtä birä!

'May our abundance be great!'

[18] K'äsäry Wastyrdzhijy xorzäx nä wäd; nä k'äsär fidar kuyd wa, nä fändägtä ruxs kuyd woj, Xuycaw wyj zäğäg!

'May the mercy of St George of the threshold be ours; God ordains that our threshold will be strong, that our paths will be light!'

[19] Enyr wazägäj či 'rbambäldi, wydon där amonddzhyn kuyd woj, ucy amond nä wäd!

'May that fortune be ours, (namely) that indeed anyone who has met (us) as a guest may also be fortunate!'

[20] Kusärttag qabyl wäd! Afädzäj-afädzmä dombaj bärägbontä kuyd känäm, Xuycaw aftä zäğäg.

'May that which is offered in sacrifice be sufficient!God ordains that we shall hold great feast days from year to year.'

For the sacrifice, the ram's throat was pierced with a dagger and its neck cut so that the blood spurted into a bowl, placed below the step, where three men held down the ram. The head was cut off first. Then the hind feet were cut off and carefully placed next to the head. The carcass was hung upside down, using a revealed rear leg-bone as a hanger, as is usual elsewhere. After the carcass had been skinned, the skin having been eased from the meat by hand, the carcass was gutted and then cut into joints for boiling, the shank being left hanging. It takes one to two hours to boil a year-old ram, two to three to boil a bull.

For the sacrifice, the ram's throat was pierced with a dagger and its neck cut so that the blood spurted into a bowl, placed below the step, where three men held down the ram. The head was cut off first. Then the hind feet were cut off and carefully placed next to the head. The carcass was hung upside down, using a revealed rear leg-bone as a hanger, as is usual elsewhere. After the carcass had been skinned, the skin having been eased from the meat by hand, the carcass was gutted and then cut into joints for boiling, the shank being left hanging. It takes one to two hours to boil a year-old ram, two to three to boil a bull.

c. Feast Structure and Customs

On every early evening of the seven days of the festival, the same ritual feast is eaten, usually with only men present, at a different home every day. Feasts tend to end before nine when everyone wants to watch the news on television, which was usually turned off during the feast, sometimes after a struggle. I made recordings, without transcriptions, of three ceremonies. The Elder sits at the head of the table. He has control of the ceremony and toasting. If the oldest person present is not well enough for this exhausting task, the next oldest is usually chosen. On his right sits the guest of honour, which was always (exhaustingly) me. It was like Christmas being held every day for a week. I managed four out of seven feasts, as, thanks to the railway timetables, I arrived at three in the morning after the first and left at three in the afternoon before the last. I also had one relatively free evening.

On the Elder's left was the next most important guest, and so on, first guests and then family, zig-zagging down the table to the youngest man, who sat at the far end. In some homes, there were up to 14 men sitting at the table. Young boys or male children were called in at special times to take part.

Before anyone entered the room where the feast was to be held, the table was set up and laid by the women. The man who had sacrificed the bull or ram brought in its singed, boiled, and shaved head, eyes closed, resting on its jaw-bone. The reason Makhar Uruzhov gave for this is that, once, a group of legendary Nart giants were attending a feast in their honour in a distant land, arranged by a local tribe whom they had subdued. They were given meat which was not to their liking. When the Narts asked what animal it was, they did not elicit a clear answer, so they asked for the head and neck of the animal. When these were not produced, they demanded that from that day on, they always wanted the head to be placed on the table to confirm the origin of the meat. It is the honour of the sacrificer to break the head and fold it flat and lay it upside-down, opened out, on the table, and I as guest of honour was given the brain, which was sweet and tasty. The head was prepared by the tedious work of removing all the hair by singeing and then boiling and scraping, so it looked serene, in contrast to the chaos revealed when it was split open. They do not eat the eyes or testicles. I slipped in this delicate question when we were walking around the livestock market, to avoid the risk of being offered them to eat at the table had I asked then. A question is usually taken as a request in the Caucasus. In one house there was no head on the table and it was later apologetically explained that we were eating boiled bull which was very expensive and so it had been divided between several households and we had not got the head.

The neck, which is considered most tasty, was placed on the left hand side, or the right if the house were in mourning since the last year, but never directly on the middle of the head. According to Gerzhen Uruzhov, the neck represented strength, and the head, wisdom. The head may have the skin missing on the nose and behind the right ear. Nioradze, writing in the 1920s, said that such marks—like those which I saw at the fourth feast—are caused by touching with a hot coal, before the animal is sacrificed and that the sign of the cross is made on its nose.

The liver and some choice slices of meat were roasted as a kebab on a wooden spit and held up during the prayer said by the Elder at the start of the feast. During the feast, the men eat fist-sized chunks of meat and gristle surrounding the ribs.

During the meal, the shoulder-bone of the ram was inspected. The length of the brown or transparent area on the smaller fin was used as a fortune-teller. Perhaps, in a time of plenty, the bones were thicker and so more opaque. The seer then cracked the bone so that it could not be used again. The younger men tried to break the weaker front-leg bone of the ram, which proved difficult, needing many hands, much sweat and twenty minutes of straining and groaning.

A plate with a stack of three flat pies called walibach, filled with cheese, about 30cm across and 2cm thick, is placed in front of the Elder. During the Elder's first prayer, he moves a pie slightly to the left, so that God could see how many pies were on the table and judge what it signified. The top one is for the Father, the middle one for the Son and the lowest one for the Earth. Makhar Uruzhov told me that if the house is in mourning, the bread for the Son is omitted.

During the meal, a puffed-up baked meat pie, called futchin, is brought to the table. The pastry case is cut in a circle near the edge, revealing a large flat "hamburger" which has stewed in its own fat. The pastry is dipped into this greasy delicacy.

A bowl is filled with buza and placed before the Elder. Buza is a thick, malty, usually sweet beer, made from a flour of dried wheat which has been soaked in water for a week, so that it is just sprouting. There were many drinks: a jug of buza and glass decanters of home distilled corn liquor, about 25-30 degrees of alcohol, called araka, and sometimes grape juice—cut with liquor, Russian vodka, brandy, champagne or, thank God, mineral water. Toasts are not drunk with buza.

The order of the ritual may vary at the command of the Elder, but it is generally as follows:

1. The Elder raises the filled bowl of buza level with his face, but does not drink. He says a prayer, and passes the bowl to the youngest male relative at the other end of the table. (Father and son are not allowed to sit at the same table. In one instance, the father gave his place to his son and was not present. This prayer, like others, is frequently punctuated with loud growls of amen from around the table. The others all drank from their small mugs of buza.)

2. The Elder says another prayer whilst holding up the top-most cheese pie. He then takes one bite and replaces it, moving it slightly to one side, so that God may see that there are three pies on the table.

3. The youngest man present says a prayer whilst holding up the filled bowl, which is then placed on a side-board behind him.

4. Sometimes the male baby of the family is brought in and given a sip of buza from the bowl.

5. The Elder starts the series of toasts, which must be drunk in the following way, unchanged since the times of the Sarmartians, they said. A variant of each toast is repeated, in order of seniority, by all sitting at the table. Toasts are usually made standing, in threes. (It could be any odd number—even numbers are used for mourning or funerals, even regarding the number of flowers a guest brings.) The trinity was thought to represent Life or the Sun, Earth, and Water. The glasses are clinked together, and if one person respects another, he will show this by touching the top of his glass against the bottom of the other person's glass. The person who has made the toast, drinks his glass to the bottom and sits down. Before the Russian Revolution, great drinking horns were sold in the shops instead of glasses. The metre-long horns could not be put down until they had been drunk empty. The next man in line down the table gets up to make the three for the next toast and so on.

d. Nine Obligatory Toasts

There are nine obligatory toasts. The first and last are drunk by all standing. For the last toast, everyone had to stand so that the seats could be removed, to finish the feast. That is why someone always must remain seated, whatever the Elder orders as a special toast. This person resents having to sit as he cannot honour the toast. The Elder often good-humouredly threatens punishment to anyone who makes a mistake with the ritual or who will not remain silent during the toasts or to tease his guests or family. I must have made over fifty toasts without repeating myself, during the four feasts. It was exhausting.

The nine compulsory toasts are as follows:

1. Sterkhosauo to Veliki Bog, great God.

2. Georgoba, the festival of St George.

3. The family's health.

4. The elder's health.

5. The guests' [both strangers and neighbours at table] health.

6. The elders and the young exchange a special toast explained below.

7. The health of those sitting at the table.

8. The bread and salt, representing food and prosperity.

9. Parog, the threshold of the room.

e. Three Additional Toasts

1. The most important guest has to make a toast. (This was always me.)

2. The sacrificer cuts off the right ear of the head on the table. (The left is cut off for a funerary feast.) The ear is then cut in three vertically. The three eldest people present place the section of the ear on top of their filled glasses which are then raised and passed to the three youngest, who pass theirs back, respectively, and everyone, respectively, makes toasts. According to Gerzhen Uruzhov, the toast of the elder (spoken in Iron Ossetic) was 'That the young should heed the old to be wise in his head and strong in his neck'. The young eat the ear and drink the glass in one. This was said to symbolize passing the cup to the next generation. At a relatively empty table, I was the oldest youngest. The ear was sweet and crunchy.

3. Three filled glasses on a plate and a rib of meat are given by the Elder and taken by the youngest to the kitchen for the women. The empty glasses are brought back later.

f. Songs

Songs were also howled, late in the feast. I recorded a couple of songs at one feast, but at the others there were no songs because there had been a death in one of the families present. This may explain why songs seem to be dying out. In 25 years of rich field work, Tamara Khamitsaeva of the Vladikavkaz North-Ossetian Institute of Humanitarian Studies has collected from old men informants only nine relevant songs, seven of which praise St George, and the other two of which praise the related St Wasilla. (Appendix 2) Eight songs are in Iron (see transcriptions 19-26) and one in Digoron (slow-spoken recording by TK; transcription 27). Her Russian transcriptions of the 5- to 20-line songs were translated by David Hunt.

g. A Miracle Reported in 1992

According to an article published by the Institute of War and Peace Reporting in the winter of 2002 ('North Ossetia Honours "Pagan" Saint George', 28 November 2002, Ksenia Gokoyeva, IWPR), schoolchildren in the small town of Digora reported seeing an extraordinary vision of St George in full pagan glory, which local journalists had no qualms calling a 'milestone in the renaissance of Christianity in North Ossetia'.

The children were playing ice-hockey on a frozen river when they reported seeing a huge horseman clad in white, riding a three-legged steed, who descended from the sky onto the roof a nearby house. The apparition uttered two phrases, 'You have stopped praying to God', and 'Look after your young people'.

For two weeks afterwards, the marks made by outstretched wings one and a half meters on either side and the deep imprints of the horse's hooves could be discerned on the roof, locals said. Snow did not fall on them and they did not melt in the sun. A church was built in Digora in honour of the vision.

Citing further proof of the single divinity of their god, mountain villagers said that both Christian and pagan shrines were spared by natural calamities that year. This summer a flood inundated all the houses in the village of Verkhny Fiagdon, but left the church of the Holy Trinity untouched. And the avalanche of ice that overwhelmed the Karmadon valley this autumn stopped just short of the shrine to St George.

'There's no coincidence here,' said Mikhail Gioyev, a local historian. 'Wastyrdjy is the favourite divinity of the Ossetians, the protector of men, travellers and warriors, but the main thing is that Wastyrdjy is the intermediary between God and Man, the people's ally, always ready to help them.'

6. The National Pagan Shrines

21 November. On the way to the great shrine at Rekom, we passed two other old shrines as well as a more recent memorial. The first shrine (I understand that it may well be Styr Xoxy dzuar, mentioned by Anna Chaudhri earlier) was a barrel-sized hollow in the rocks five metres up a rock-face near Tamisk, where the road to Rekom forks from the main road. It was considered lucky to throw coins up into the hollow. There was a table on the ground below the hollow with a couple of empty water bottles. 10km further on, we turned off to the left of the main road and swung back downhill to the village of Nuzal. The shrine there was a beehive-roofed rectangular stone church, protected by a corrugated tin roof during restoration. Inside the locked building were murals, (illustrated in Rekom, Nuzal i Tsarazonta, V.A. Kuznetsov, Vladikavkaz, 1990), including named portraits of Christ Pantocrator, proto-saint Romanoz, Ktitory Aton and Jadaron, Ktitor Fidaros with the Georgian name Soslan, and Mary-Mother-of-God, John the Baptist, the Archangel Michael, St George spearing the serpent, and St Evstafii firing his bow at some deer. On the mountain opposite were the ruins of Nazgin and behind on a rise were the ruins of the fort and walls of the village of Totit'e.

Vitali Tmenov, local archeologist, aged 45, accompanied us as our guide. On the far side of the river Ardon, we passed a pointed arch which seemed to have been carved from the rock chasm for the old road to Rekom. Climbing above the snow line, we paused beneath a huge flat rock, painted with a giant bust of Stalin in uniform, adorned with the adoring inscription, a punning swipe at the alpine shrine, that 'for us, Stalin is the highest authority'. Vitali said that the earliest Scythian finds in the nearby Koban region dated from the 16-17th centuries B.C. The Sarmartians came here in about 500 B.C., followed by the Alans in about 500 A.D., whom the Ossetes consider to be their ancestors.

a. The Three Shrines at Rekom

—Rekom — the main shrine

The main wooden shrine is for men, while two smaller shrine-huts further downhill in the woods (of more recent but similar log-cabin construction), are for women and children, respectively. The roofs are decorated with one-metre high wooden swan-necked finials, crowned with carved birds. In the main shrine, the finials seem like skyward extensions of the octagonal, irregular, vertical swag-shaped wooden columns which support the roof, forming an arcade on both sides. Whilst there are horns, skulls, and empty bottles outside the Men's shrine, the other shrines have white and coloured ribbons tied to sacred trees. At the deserted shrine, the early afternoon twilight played magic tricks with the colours and contrasts were set off by patches of snow on the ground.

b. "Tbao-Wasilla", the Shrine of St Wasilla

According to Luidmilla Holt, Tbao-Wasilla is a sacred mountain in the usheli (region) of Dargavs, near the village of Kakadur. Luidmilla's father was born there, so she was brought up with the story. It is not very far from the 'City of the Dead' just up the hill. The shrine of Tbao-Wasilla is one of the most ancient in Ossetia, dedicated to Wasilla since the time of the Alans (c. 5th century A.D.), according to Kaloev's authoritative book Osetiny. There is a festival held there in summer just before the mourning (?) season, observed by people from Dargavs usheli and Kurtatin Gorge. They sacrifice a sheep in every house and later hold a festival on the top of Mount Tbao, where both men and women are present. It is a very happy occasion and Luidmilla attended one ceremony when she was eight or nine years old. St Wasilla is prayed to alongside St George in the 'Priest's Blessing of Offerings of Festival Food and Drink' at the shrine of St George, Dzvgisy dzuar, described below. Accordingly, two songs to St Wasilla are included in Appendix 2.

c. "Dzvgisy dzuar", the Shrine of St George

—Dzvgisy dzuar

On Sunday 24 November, the most important day of the festival, hundreds of people drove the 45km south-west of Vladikavkaz into the Kurtatin usheli, in the Alagirski region, to the shrine of St George, Dzvgisy dzuar village, next to the burbling river Fiagdon. Hasan wrote that near the church are the remains of stone containers from an earlier memorial built about 500 AD, considered to be the earliest Alan monument in the Caucasus. The present church was built around 1200 and restored in 1902.

7. The Ceremonies held at the Shrine of St George

On Sunday, the most important day of the festival, hundreds of people drove the 45 kms south-west of Vladikavkaz into the Kurtatin usheli, in the Alagirski region, to the shrine of St George in Dzvigis [?Dzuuvis] village, next to the burbling river Fiagdon. Hasan wrote that near the church are the remains of stone containers from an earlier memorial built about 500 A.D., considered to be the earliest Alan monument in the Caucasus. The present church was built around 1200 and restored in 1902. From a distance, the shrine was invisible, surrounded by sacred trees and fifty cars. At about midday, men, women, and children packed the sunny kidney-shaped courtyard, passing through the narrow entrance, next to an elevated brick frame on which were hung two small old bronze bells, with Georgian inscriptions. To the right, the local village priest, Taitluraz(?) Elkanov, 59, was standing on a metre-wide raised rock platform on one side of the open courtyard. He blessed the food and drink, laid out at his feet along the length of the platform. The food was bound in white kerchiefs, laid open for the blessing. There were round flat loaves with cheese inside [prepared by women] and boiled meat on the bone [cooked by men], and glass decanters of home-brewed clear liquor and buza beer. After the blessing, the food was removed and eaten in the feasting hall or outside, on the grassy slopes, near some beehive-roofed stone tombs.

a. The Priest's Blessing of Festival Offerings of Food and Drink

[1] [formula] O God, tabu [praise] to you, O God!

[2] One day, when we find Your name, then we will make the work of a hundred days.

[3] Today is the honoured day of your wishes, O God, and of those of good men who wished the younger men good fortune and to make them friends [i.e. not just children], O God. [?referring to the drink and toasts].

[4] The making of wishes is highly esteemed work in Iron country, and strongly, from our priests and from their time.... If their wishes help from the oldest to the youngest, then it is made so that it will really help our wishes for our guests, who have come to us [?]. Please let this happen, O God!

[5] Make our guests happy, by the kindness of our holy saints, O God!

[6] There are many saints in our valley. They are St Khusaw [the father of Khristos], St Ziri and St Tkhoshte, and make them help those who are praying! Grant this, O God!

[7] O St George, you are an honourable saint and a strong saint and make healthy and happy all those who are walking beneath you! Make them happy and grant that they walk and live in health!

[8] O God, make the people, who are going about beneath you, so that they will return healthy to their homes, and without illness.

[9] The owner of the mountains [the eponymous] Wasila [god of wheat]! Tbao [?saint] Wasila! Tabu [prayers, praise or thanks] for your kindness! Grant it that the people have their wheat for their livestock. [The priest blessed the meat laid out in front of him.] Grant the people that they find their own name and the name of their God! Grant this, O God!

[10] Those who come here to pray today, both men and women, grant them their well-being from your kindness, [?O Wasila]!

[11] From the time of the rising of the sun [about six] to the time of the setting of the sun [about three thirty], every saint who exists said, that if a man found out his [the saint's] name, that he [the saint] would help him. Grant us the benevolence of the saints, O God!

[12] And now, we never, never have anything greedy [grasping or devious?] from our prayers. But we can say that these ch'iri [the round cheese-filled breads, laid out in front of the priest] make the house from where they came happy. Make their parents happy! Please take our bread, O God!

[13] Give long life to the man who tastes this bread, O God [Khusaw]!

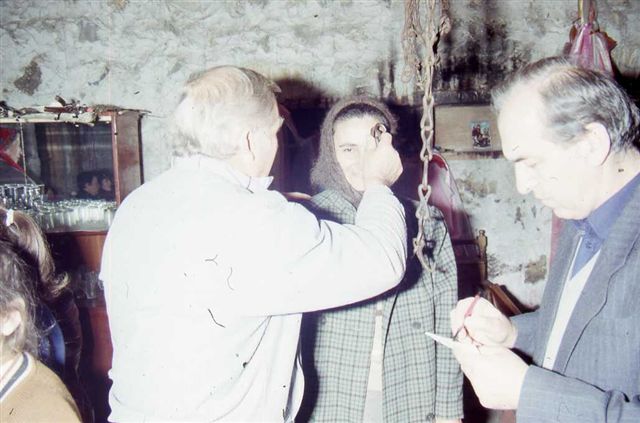

b. The Priest's Blessing of Those Present with a Hearth-Chain

The priest then blessed men, boys, and even male babies, individually, on the raised rock platform upon which he stood. One end of a hearth-chain is fixed to the back wall of a niche behind the platform in the courtyard. The priest filled the niche, tying on more and more brightly-coloured bands of cloth, hanging down, layer upon layer, while beneath, over the floor of the recess, a broad wooden nest of miniature shelves was stuffed with rouble notes. A blessing had no fixed price. He gently, yet firmly, held the free end of the chain against the forehead of the supplicant before and during the blessing:

The priest then blessed men, boys, and even male babies, individually, on the raised rock platform upon which he stood. One end of a hearth-chain is fixed to the back wall of a niche behind the platform in the courtyard. The priest filled the niche, tying on more and more brightly-coloured bands of cloth, hanging down, layer upon layer, while beneath, over the floor of the recess, a broad wooden nest of miniature shelves was stuffed with rouble notes. A blessing had no fixed price. He gently, yet firmly, held the free end of the chain against the forehead of the supplicant before and during the blessing:

'O, St George [holy word], thanks be to those who do good deeds. If any people are bad or dishonourable, may they fall. If any wish to live a good life, bless them, their relatives [including their neighbours], and their young, and may God help them. O, St George [holy word].'

At the end, he moved the large last link of the chain before the lips of the blessed to be kissed. I was given a three rouble note to give the priest after the blessing, but I thought it a bit mean, so I gave him another ten.

Meanwhile, the food was removed by the women and taken inside the feasting hall, where one side was for men and the other for women. In the middle, two hearth-chains hung from the ceiling, one hooked into the other forming a loop, while the loose end was used by another priest to similarly bless women and girls. On either side, the two wooden piers supporting the ceiling were swollen with hundreds more colourful cloth bands. Away from the courtyard, on the far wall of the men's side, were three modern pictures of St George on horseback, slaying a dragon. Further down the long table, above and behind two seated men who were drinking to my health, was a portrait of Stalin. We were sat down at the men's table and were given glasses of home-brewed liquor, while I was hand-fed boiled meat and ch'iri walibach (pies stuffed with cheese) to prevent my hands getting greasy while I was taking pictures. Hasan got carried away and was trying to get me to drink, while his friend who had driven us there in his own car met a young shiny-faced self-professed healer who, drunk and excited, followed us until we escaped after midnight.

8. Epilogue: A Sacred Bull's Horn from Rekom

A sacred bull's horn from the shrine at Rekom was my birthday present to Prof. Sir Harold Bailey (1899-1996) on 16 December 1991, to thank him for his continued enthusiastic encouragement of my visit to Ossetia. After retiring from Queens' College, Cambridge, he jointly set up a charity called "The Ancient India and Iran Trust", where he lived with his library at 23 Brooklands Avenue, Cambridge. His birthdays were customarily celebrated by many well-wishers with a large cake on which a sentence, exhortation, blessing, or word in one of his 70-odd languages was written in icing. He would then explain its meaning to a bemused audience. The speed of his delivery coupled with his assumption of their level of knowledge meant that most of them were often left behind. His long-time colleague and speaker of Ossetic Dr Ilya Gershevitch (1915-2001) of Jesus College, Cambridge, who visited North Ossetia in the 1990s, was also a most welcome long-term supporter of this project.

This sacred bull's horn was boiled several years ago, after sacrifice at Rekom, the most important pagan shrine in North Ossetia. It was left with many other horns and a few skulls of bulls and rams on a bench built against the front wall of the shrine. Dr Vitali Tmenon, archeologist at the North Ossetian Humanitarian Institute of the Academy of Sciences presented it to Robert Chenciner on 20 November 1991, when they visited the alpine shrine. For more details see the illustrated book Rekom, Nuzal i Tsarazonta, by V.A. Kuznetsov (Vladikavkaz, 1990).

Appendix 1. First Feast—Vladikavkaz, 20 November 1991

(Transcription and translation by Luidmilla Holt)

(What follows may sound somewhat rambling, but the large number of obligatory formulaic toasts and the resultant hangovers is one reason why few outsiders have ever succeeded in completing research about the Caucasus. To avoid this, I often appointed people to drink on my behalf. It is possible to speculate that the repetition is redolent of an epic poem.)

There is a noisy background with much downing of toasts, in an all-male group.

'At their weddings, at their good deeds, at good news, shall we meet always, may God wish it. Be loved by people, by neighbours, and loved by God, then everything in the world shall be yours. Long live your family. Amen. Amen God.' [a man is translating to me from Iron]

'Have you drunk? Trofim, to your health! For the sake of this festival may your life be beautiful and happy—to your health! For God's sake, he is our guest and to those who make him welcome, may God wish well. You are to live well for us all.—He doesn't eat… May all be good at the festival. May Trofim our host and head of the family be well.—Be beautiful and well.—He is recording this.—Don't worry Trofim, let them listen.—Let us ask God to be strong through happiness.—Dzerassa and Trofim, be happy by the lightness of your children. Let your family life be strong.—How interesting, he clearly speaks Digoron—have you taught him?—Yes. (He argues good-humouredly that he is Ossete, but the others reject this saying that his father once 'sat in a carriage' with an Ossete. At the end he gives in, saying that he is Digoran.) Don't shout! (another voice)—To your health!

Young man's toast: 'Here we all sit in Trofim's home and celebrate the Djiorguba (Wastyrdjy) festival. We sat here yesterday, but today we have a guest from a different world. (He then toasts me in Russian)—Your health! (and I speak) So, Trofim, today we sit with a guest from far away, and he traveled a long distance because he wanted to sit with us during Djiorguba, and whatever job he is doing, may his heart be happy and be uplifted by his work.—Amen, God. And whatever plans he has made by coming here as a visitor, may he achieve them well and may he return home safely.—Amen, God. And may he tell everything well of the news and business of his visit and may God give him the energy to do so.—Amen. May God never take away the destiny of your guest. A bad guest should never cross your threshold. I say so, and an Ossete says it too. If you somehow succeeded in crossing my threshold, then you should return home well, whoever you are, after being in my home.—So he should never say, that I left Trofim's house and something bad happened to me. So let God make his benefit big, so you should give him a toast! (drinks) Maybe his heart prefers to drink wine? (They ask me what I preferred)—Why did you get up? (one asks).—I am giving a drink to a guest, he sits right near me, and so it is not surprising that I stood up. It's out of respect. (I am speaking in English; they are encouraging me to get drunk; sounds of glasses clinking.)

Another toast from a different man.—'Fiodor, thank you very much for your words. I was very happy that you have shown respect to our guest. When a man respects his guest, then he respects himself. So we must firstly love ourselves, may God say so, and then love another person. So thank you very much. (drinking)—Has everyone got a glass?—May God make you healthy and happy; may your life be long! (continues in Russian. I am having a good time and laughing)—To your health! (By now I am getting drunk) (In the background) To your guest's health; everyone drink their toasts!—I made a toast for Djiorguba and for a guest.—To your health, all!

(Another voice) Hasan, does he know that it is an Ossetic name? (unclear) Of course I want to speak in pure Digoron, but the elder does not permit me. He doesn't understand.—His friend knows over 30 languages, he says. He himself went to Makhachkala (capital of Daghestan) five years ago. (continues in Russian)—Come in, come in.. (woman's voice in background—apropos of people from Britain, they mention Luidmilla by her maiden-name Dudieva from Beslan; she can't believe her ears. They continue talking about languages in Russian)—He is our guest and we must treat him well—Soon you will be writing 'Digoron' as your nationality in your passport. (I was talking about Avar language in Daghestan. They prepare for another toast. I ask them to speak in Ossetic not Russian. They say fine—it is not normal for them to make a toast in Russian.)

Next toast—'So I say that may Trofim's parents' health be good and may they continue to be healthy and without problems. We know them and they are gentle and pleasant. He is probably of the same gentle sort, as we know him, and may God grant them long lives. Amen to God. And may they be under His protection. As I say, someone who does not respect their elders, who does not love their mother or their father, that person would never love anyone at all. (someone adds) ...then he doesn't love himself.—It is easier to love the Earth than your mother and father, because if you say 'I love the Earth, that means that you don't love anyone'. That's how it is reckoned in theory, but you have to respect your own mother and father, visit them, help them, sit by their side. And Trofim's mother and father and others whose parents are untroubled and healthy, may God grant them long lives!—Amen to God!—And let's drink to them standing-up, as they are our parents.—We can't avoid that toast.—My mother is alive and I shall drink to them.—Our elder has approved and we should drink to their health. (drinking all round; and talking about Trofim's parents:) To their health! (one voice) One who doesn't have respect for their elders, is not a man! (another voice). No one crawled out of a crack in the wall, but parents have to work too hard! When a child is born, and until he is grown up and can help himself and look after himself, there is so much hard work that needs be put into him. And they who understand that, long may they live! Amen to God.—And so let your mother's and father's love be long and good, and as your neighbours we do understand each other. You are doing a good job, good things, and may your family be under your direction. And all the best of Djiorguba will be yours. But never forget about your elderly, may God grant you that. Amen. (Glasses clink.) Look after them, happily and beautifully. (interruption) Nobody knows who will end up looking after whom! (laughter, then talking about his father and that this is his house) May their lives be as good as his life, so that we can see their good achievements. May God grant it! (in explanation…)—we are drinking to the health of our family, our elders (to another) Why are you looking so worried? Are you worried about something?—No, I am not worried! We must not forget about the one who gave us this opportunity to see this man (probably me) and we must give him the chance of a toast—Don't worry everyone will have the chance of a toast. (I am asking them about Sunday, worried that I have missed the sacrifice, but they explain that there is a separate one on each of the seven days of Djiorguba, shared out between the neighbours. Relatives are welcome, but for neighbours it is compulsory. (Another toast is being prepared.)

Next toast—'Let's listen to each other again. Right now we are saying that we are neighbours. We talked about Robert too, how he came to us from far away, and we said a prayer for him, that God may prolong his life. But we must say a few more words about ourselves, as we are neighbours and may God help us understand each other. Amen. Everyone knows that a fist is stronger than just five fingers. And when we are doing something together, and our hearts are tied together, then we shall be much stronger together. And may God make us strong! Amen to God. All kinds of things may happen, and in all matters we should not hide from each other, but help and visit each other. Nothing is better than a neighbour. Perhaps some of us do not know this, but it is well-known to me. In my 30 years of adult life I have had several, and speaking frankly, only once did I not have a good neighbour, but all the other times I was fortunate. I have trusted them with everything, even my children, and until my return from Orenburg (on the Ural river) everything was taken care of. That meant good neighbours and good people.—For God's sake, as the Ossetes say, that if a tree falls down, it firstly falls on a neighbouring tree and the first one it hits is its neighbour. It's the same with us. So we shouldn't be defeated by the neighbour's fall but help each other. If the tree falls it means that something is bothering it. So we should have that strength to recover. And may your lives be long and good. (Interruption)—Our elder gave a toast to the health of our neighbours and may they live a long life. And it seems to me that we are not a bad neighbourhood. (voices) Yes! Yes!—And in future maybe we shall be even better when we understand each other. May our good-will be heard from far away. May God wish you health and goodness. (I am next speaking about safety on the streets on London and Vladikavkaz. The tape ends.)

Appendix 2. Nine Songs about St George, and related to St Wasilla.

(Translated from the Russian by David Hunt.)

SUBLIME WASTYRDJY

O Wastyrdjy, you know we pray to you, soy,

You know we pray to you, soy!

Our people here are praying to you, you know, oy!

Your shrines are on every hill,

And your work tools are in every ravine.

Our people here are praying to you, you know,

We are praying to you with dark beer,

With golden kebabs, with three pies.

Have pity on us, your poor people.

Where are you, where have you got to, flashing-eyed Wastyrdjy?

We have needed you!

We entreat you from afar!

THE SONG OF WASTYRDJY

There from the summits Wastyrdjy is gazing,

May it be tabu [a sacred event] for him!

Here below the people pray and entrust themselves to you.

There in the mountains are our hunters,

They will bring us a good quota dispensed by Afsati!

There on the Fansiuaran are our herdsmen,

They are returning to us with plump herds, with copious issue!

There on the plain are our ploughs,

They will bring us a harvest and the joy of autumn plenty!

There are our travellers from all ends of the earth

Returning to us, happy, with their rich gains.

In the name of them all we make you gifts and offerings,

May it be tabu for you!

["Afsati" is the deity patron of animals of the hunt, represented by a horseman on a deer. (Mythological images in Scythian-Sarmatian culture, Culture of Barbarian Europe, A. Fantalov, ND)]

MOUNTAIN WASTYRDJY

Let Mountain Wastyrdjy deign to bless us, Mountain Wastyrdjy!

Let the requests of your praying people be answered well, Wastyrdjy!

May you bless the people who are praying, Mountain Wastyrdjy!

Won't you look from the heights, and bless us in the depths!

Hey, hey, Wastyrdjy of the sturdy mountain, you know we are living and hoping on you.

Our offerings, which we made with love, may they be pleasing to you.

We are praying, hoping on you, both in the mountains and on the plain.

Both our traveller and the one sitting at home

May they be under your protection, Wastyrdjy.

WASTYRDJY

O great Wastyrdjy of Gular(a)

Go before us, and guard us from behind too!

Bless our journey

Over the high pass,

Great Wastyrdjy of Upper Gular(a)!

THE SONG TO WASTYRDJY

Oy, oy, tabu to you, glorious Wastyrdjy, oy, we pray to you!

You know we are asking you for prosperity, hey!

Oy, oy, our creator—the great God,

O our mother—Mady Mayran, who makes

A man from a boy, a horse from a foal.

Oy, oy, our fellow traveller Wastyrdzhy, we are your guests:

With your righteous wing shield

The traveller from an evil bullet, hey!

Oy, oy, our beloved Wastyrdjy,

Protect our harvest from an evil downpour and hail, hey!

Oy, oy, patron of cattle Falvara, patron of corn Wasilla,

Let there be great glory to them, hey!

Oy, oy, great Wastyrdjy, enthroned on the summit,

The hay from the North slopes is feed

For the sacrifice animal destined for you,

Oy, oy, glory to you our Wastyrdjy, glory to you!

The wheat from the South slopes is for your feast

That happens every year, hey!

Oy, oy, glory to you, our Wastyrdjy.

Bring us the horsemen that were born in the saddle, hey!

WASTYRDJY

Come, let us pray, let us sing hymns to Wastyrdjy,

We are under his protection, under his protection, children!

Look down from the heights, look on us,

Our golden-winged one:

Here are your poor guests

Under your protection, Wastyrdjy!

Even a guest is under your protection, Wastyrdjy!

Even the host is in your safe-keeping, you sitting on the summit!

If you are going in front,

Then guard us at the back!

If you are going behind,

Then cover us with your wing!

Well, the straight path, the straight path,

Our golden-winged upright Wastyrdjy!

Look down on us from the heights,

While sitting on the summit, guard us on the plain

We are under your protection.

THE SONG ABOUT WASTYRDJY OF THE MOUNTAINS

Uarayda-ra, ua-hey-da-ra,

Heyt, uarayda-ra, hay-hay!

Golden-winged lofty Wastyrdjy of our mountains!

Our golden, lofty Wastyrdjy, who provides us with cattle!

Our travellers are there on the plain,

Our travellers are your guests,

Lofty Wastyrdjy of our mountains!

THE SONG ABOUT WASILLA

On every hill are your shrines,

All our old men [elders]—our people are praying to you,

Our old women are cooking sacrificial pies for you,

Our young girls are carrying water for you,

The best of our youths are extolling your name,

They are making merry in your name.

We are under your protection, glorious Wasilla!

You are our protector!

The corn from the near fields is for sacrificial pies

In your name,

We pray to you from the first crop!

We pray to you also for the best animals!

THE SONG ABOUT WASILLA

Khor-Wasilla, direct your favour on us!

Wasilla will give us corn, uay!

Falvara will endow us with cattle, uay!

You are enthroned there on the summit, uay!

Ua-ay-i, deign to let your favour fall on us,

Ua-uay, so then, good Wasilla, uay!

Ua-ay, direct your favour on us, uay!

Look and take notice of us, uay, uay!

Direct your favour on us, Khor-Wasilla, uay!

Text and photographs © Robert Chenciner

Unless stated otherwise or obviously not the case, all the text and images on this website are © A.J.T. Bainbridge 2006-2014

Do get in touch! Gmail: alexjtb