The

GERMAN PUSH

up into the

CAUCASUS MOUNTAINS

during the Second World War

August 1942 — January 1943

A WORD OF WARNING:

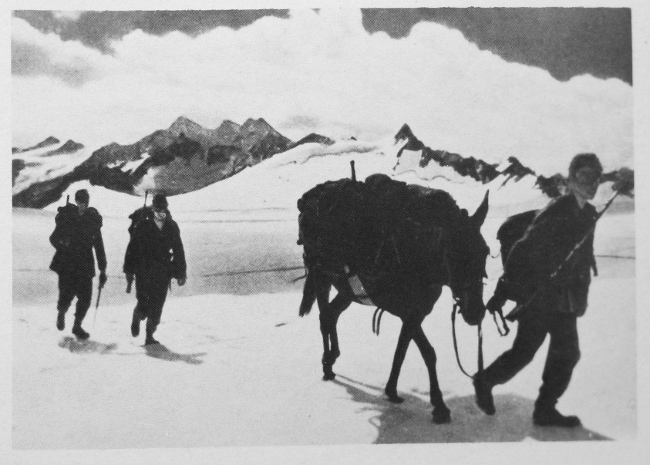

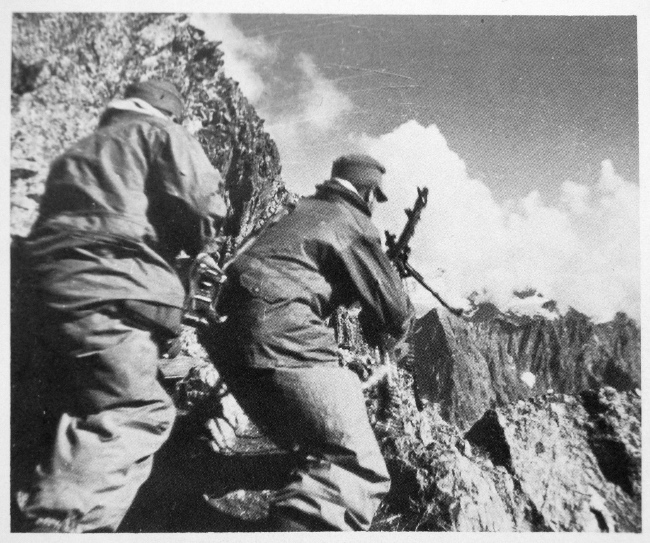

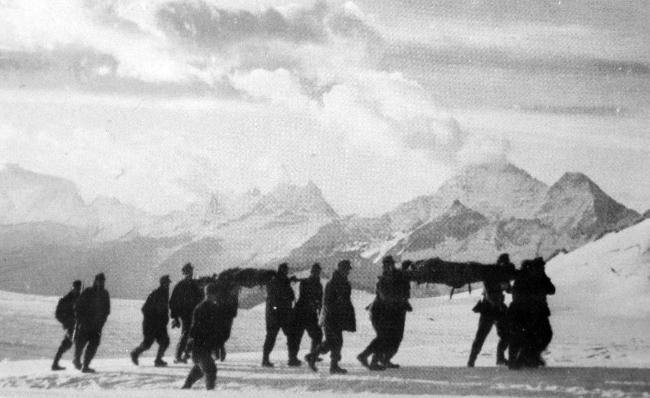

The delicate smell of alpine flowers and the aura of romance (see here, for example) which float over the men of the German Army's elite mountain warfare divisions—who were in any case naturally not as well-groomed as the propaganda of the time suggested—are just as misleading as the glorious "liberation" of the Caucasus by Soviet forces following their retreat.

|

ATTEMPTED |

|

|

|

PROBABLE |

The officers and men of both the 1st and 4th Mountain Divisions are suspected and in some cases were accused of war crimes and direct complicity in the mass murder of Jews, Bolsheviks, partisans and civilians during operations in Eastern Europe, Russia, the Ukraine, Greece and the Balkans during the Second World War—particularly the 1st "Edelweiß" Division, which was complicit in the mass murder of thousands of "Jewish Bolsheviks" in L'viv in the western Ukraine in the summer of 1941, brutally repressed and shot partisans and civilians alike in the Balkans and northern Greece in 1943 (where the wretched dregs that remained of the original unit after its mauling on the Eastern Front in 1942 had been sent to do just that), and took part in the ruthless clearance and deportation to Auschwitz of the entire Jewish ghetto of the northern Greek town of Ioannina in the spring of 1944 (to name only these three outrages).

The Germans were, inevitably, very good at being the "baddies" and committed or were complicit in some truly heinous crimes during the Second World War. As far as the Caucasus was concerned, however, its myriad peoples suffered most horribly at the hands of their own Soviet "liberators", who imprisoned, shot, exterminated and deported entire peoples of "undesirables" in the region following the German withdrawal—often based upon spurious accusations of complicity with the enemy, and always using the isolated actions of a few as a convenient excuse for getting rid of the whole.

In February 1944, for example (for there are so many others), around half a million Chechen and Ingush men, women and children—i.e. all of them—were brutally rounded up in their villages, marched down to waiting cattle trains at gunpoint, and sent away to fight for their very survival on the wintery steppes of Central Asia. The elderly, invalids and others who could not walk were murdered, and the Chechens and Ingush joined the growing list of Caucasian peoples Russia simply wiped off the face of their earth and from the pages of its history books (the "Circassians", the Balkars, the Karachai, the Meskhetian Turks, &c.).

'Between 1926 and 1939,' writes Oliver Boullogh in his Let our fame be great—Journeys among the defiant peoples of the Caucasus (London: Allen Lane, 2010—the most recent and perhaps the best account of these atrocities), 'the Chechen population grew by 26 per cent. In the next twenty years, it grew by only 2.6 per cent. The suffering that caused that statistic is indescribable.'

JUMP TO:

— Prälude: Führer Directive No.45

— 1. The forces in place (National-Socialist and Soviet)

— 2. From steppe to mountains: the advance to the Caucasus and the first ascents

— Interlude: the German ascent of Mt Elbruz

— 3. Over the main ridge: the Germans capture the passes

— 4. Struggling down the southern slopes towards stalemate and retreat

Annex

— A German Gebirgsjäger's experience of the whole affair

(Press the "home" key on your keyboard at any time to return here.)

SOURCES:

The information on this page is obviously somewhat one-sided, for it consists mostly of personal accounts of the fighting written by Germans (mostly Tyroleans and Bavarians) who served with the German Army's 1st "Enzian" and 4th "Edelweiß" Mountain Divisions in the Caucasus between August 1942 and January 1943 (the entire duration of the German Army's presence in the area).

These accounts—( i ) the war diaries of Oberjäger [Lance-corporal] Alfred Richter, ( ii ) the official account of the capture of the Marukh Pass written by Ewald Soltke, a soldier/editor of the Germany Army's 666th [sic.] Propaganda Kompanie, and ( iii ) the memories (carefully edited by historian James Lucas into a single "story") of other, unknown, soldiers—were copied from Roland Kaltenegger's excellent Gebirgsjäger im Kaukasus: Die Operation "Edelweiß" 1942/43 (Graz: Leopold Stocker Verlag, 1997) and the chapter on the Caucasus in James Lucas's Alpine Elite—German Mountain Troops of World War II (London: Cooper & Lucas Ltd, 1980).

Most but by no means all the photographs were copied from Alex Buchner's well-researched and lavishly illustrated Der Bergkrieg im Kaukasus—Die Deutsche Gebirgstruppe 1942 (Friedberg 3 [sic.]: Podzun-Pallas-Verlag, 1979)—a truly excellent and intensely personal book self-published by a veteran of the German operations.

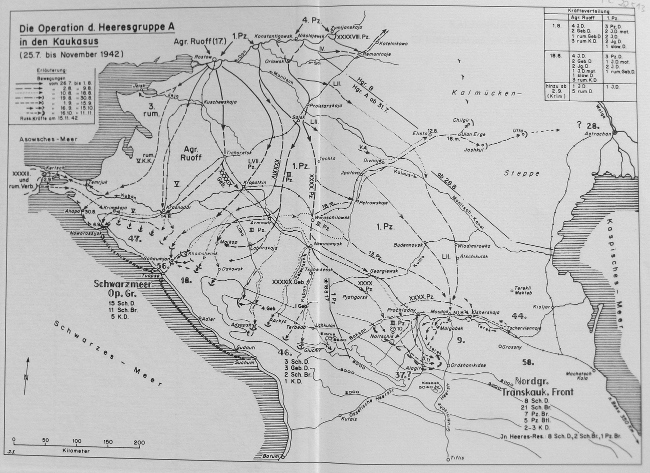

Both Buchner's and Kaltenegger's books also contain detailed maps, some of which are reproduced here.

—

For a 'highly detailed and balanced account of the fighting between the Germans and the Russians in the Caucasus mountains in late 1942' that 'takes advantage of unique access to archival sources' (both German and Russian) and provides 'many valuable insights about mountain warfare... and the military culture of the Stalin era', Alexander Statiev's excellent At War's Summit: The Red Army and the Struggle for the Caucasus Mountains in World War II (Cambridge University Press, 2018, 440pp, with numerous illustrations, maps and figures) could not be more highly recommended.

Prälude: Führer Directive No.45

[abridged]

The Führer and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces

Führer Headquarters, 23rd of July 1942

Directive No.45

6 copies

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Officers' eyes only!

Transmission only through officer!

Secret!

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

DIRECTIVE NO.45

"CONTINUATION OF OPERATION BRUNSWICK"

In a campaign which has lasted little more than three weeks, the broad objectives outlined by me for the southern flank of the Eastern front have been largely achieved. Only weak enemy forces from the Timoshenko Army Group have succeeded in avoiding encirclement and reaching the further bank of the Don. We must expect them to be reinforced from the Caucasus.

A further concentration of enemy forces is taking place in the Stalingrad area, which the enemy will probably defend tenaciously.

II. AIMS OF FUTURE OPERATIONS

A. Army

1. The next task of Army Group A is to encircle enemy forces which have escaped across the Don in the area south and southeast of Rostov, and to destroy them. For this purpose strong fast-moving forces are to move from the bridgeheads which will be established in the Konstantinovskaia-Tsymlyanskaya area, in a general south-westerly direction towards Tikhoretsk. Infantry, light infantry, and mountain divisions, will cross the Don in the Rostov area. In addition, the task of cutting the Tikhoretsk-Stalingrad railway line with advanced spearheads remains unchanged. Two armoured formations of Army Group A (including 24th Panzer Division) will come under command of Army Group B for further operations southeastwards. Infantry division Großdeutschland is not to advance beyond the Manych sector. Preparations will be made to move it to the west.

2. After the destruction of enemy forces south of the Don, the most important task of Army Group A will be to occupy the entire eastern coastline of the Black Sea, thereby eliminating the Black Sea ports and the enemy Black Sea fleet. For this purpose the formations of 11th Army already designated (Romanian Mountain Corps) will be brought across the Kerch Straits as soon as the advance of the main body of Army Group A becomes effective, and will then push southeast along the Black Sea coastal road. A further force composed of all remaining mountain and light infantry divisions will force a passage of the Kuban, and occupy the high ground around Maykop and Armavir. In the further advance of this force, reinforced at a suitable time by mountain units, towards and across the western part of the Caucasus, all practical passes are to be used, so that the Black Sea coast may be occupied in conjunction with 11th Army.

3. At the same time a force composed chiefly of fast-moving formations will give flank cover in the east and capture the Grozny area. Detachments will block the military road between Osetia and Grozny [sic.], if possible at the top of the passes. Thereafter the Baku area will be occupied by a thrust along the Caspian coast. The Army Group may expect the subsequent arrival of the Italian Alpine Corps. These operations by Army Group A will be known by the cover name "Edelweiß". Security: Most Secret.

4. The task of Army Group B is, as previously laid down, to develop the Don defences and, by a thrust forward to Stalingrad, to smash the enemy forces concentrated there, to occupy the town, and to block the land communications between the Don and the Volga, as well as the Don itself. Closely connected with this, fast-moving forces will advance along the Volga with the task of thrusting through to Astrakhan and blocking the main course of the Volga in the same way. These operations by Army Group B will be known by the cover name "Heron". Security: Most Secret.

B. Luftwaffe

The task of the Luftwaffe is, primarily, to give strong support to the land forces crossing the Don, and to the advance of the eastern group along the railway to Tikhoretsk, and to concentrate its forces on the destruction of the Timoshenko Army Group.

In addition, the operations of Army Group B against Stalingrad and the western part of Astrakhan will be supported. The early destruction of the city of Stalingrad is especially important.

Attacks will also be made, as opportunity affords, on Astrakhan. Shipping on the Lower Volga should he harassed by mine-laying. Secondly, sufficient forces must be allocated to co-operate with the thrust on Baku via Grozny.

In view of the decisive importance of the Caucasus oilfields for the further prosecution of the war, air attacks against their refineries and storage tanks, and against ports used for oil shipments on the Black Sea, will only be carried out if the operations of the Army make them absolutely essential. But in order to block enemy supplies of oil from the Caucasus as soon as possible, it is especially important to cut the railways and pipelines still being used for this purpose and to harass shipping on the Caspian at an early date.

C. Navy

It will be the task of the Navy, besides giving direct support to the Army in the crossing of the Kerch Straits, to harass enemy sea action against our coastal operations with all the forces available in the Black Sea.

To facilitate Army supply, some naval ferries will be brought through the Kerch Straits to the Don, as soon as possible.

In addition, Commander-in-Chief Navy will make preparation for transferring light forces to the Caspian Sea to harass enemy shipping (oil tankers and communications with the Anglo-Saxons in Iran).

Signed: Adolf Hitler

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

ESSENTIALLY, in July 1942 Hitler ordered ( 1 ) 17th Army (under Army Group A) to advance south-east down the Black Sea coast and 'occupy the entire eastern coastline of the Black Sea [sic.!], thereby eliminating the Black Sea ports [primarily Poti and Batumi] and the enemy Black Sea fleet', and ( 2 ) a "force composed chiefly of fast-moving formations" (1st Panzer Army, also under Army Group A) to 'capture the Grozny area' (oilfields), 'block the military road between Osetia and Grozny [sic.], if possible at the top of the passes,' and occupy the Baku area (more oilfields) by 'a thrust along the Caspian coast' [sic.!].

The plan, unbelievably, was to capture a line extending roughly from Batumi through Tbilisi to Baku...

The 1st and 4th Mountain Divisions of the 49th Alpine Corps were to support 17th Army's efforts by advancing due south over the high mountain passes of the western Caucasus, thus flanking and possibly encircling Soviet defences concentrated along the Black Sea coast, and link up with friendly forces around Tuapse or Sukhumi. (A Luftwaffe photo-reconnaissance flight even went as far as photographing the latter town:)

To put it mildly, particularly given the distances and the terrain his forces would have to cross to even try to achieve his fantastic objectives, and to say nothing of increasing Soviet opposition and the growing doubts of his own generals, Hitler's intentions seem somewhat disconnected from reality.

1. The forces in place

German & Soviet

THE GERMANS, characteristically, came to the Caucasus well prepared (on paper, at least): the 49th Mountain Corps (XXXXIX. Gebirgskorps) consisted of an operational s t a f f under General der Gebirgstruppe Konrad—General Lanz commanding the 1st mountain division and General Eglseer the 4th—who had at their disposal specialized mountain s i g n a l s units equipped with mules trailing telephone wire from wooden spools on their backs, linking units along mile after mile of forested valleys and steep, rocky tracks, some less fortunate radio operators spending days atop isolated rocky peaks to act as solitary relays for messages passing up and down the line; highly-trained mountain a r t i l l e r y batteries with specially-designed lightweight howitzers capable of being dismantled and transported along rough terrain, complete with their heavy rounds of ammunition, by teams of as few as 10 mules, and able to fire eight 75mm high-explosive shells per minute at enemies as far as 9 kilometres away; detachments of highly-skilled mountain e n g i n e e r s capable of moving mountains (almost literally) and building roads, bridges, motorized cable-railways for bringing up supplies and evacuating the wounded, barracks and bunkers, down in the valleys or high up above the snowline on some windswept pass; specialized mountain l o g i s t i c a l and supply units, some of them roaring around on half-tracked motorbikes designed to transport loads of up to 250kg along steep mountain tracks, most of them ankle-deep in mud with a bad-tempered mule train in tow; not forgetting the several thousand elite G e b i r g s j ä g e r themselves, tough and taciturn mountain men from the Alps (initially, at least) equipped with rifles, machine-pistols, light and heavy machine-guns, sniper rifles, hand-grenades, light and medium mortars, wheeled 20mm anti-aircraft cannon, ice-axes, miles of rope, bags of karabiners and pitons, hobnailed boots, plenty of tobacco, no doubt enough brandy and dirty jokes about their person to warm up an entire platoon, and a small white flower on their caps and uniforms.

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

The men and officers of the German Army's 1st Mountain Division wore an E d e l w e i ß (Leontopodium alpinum)—a small, delicate white flower long associated in the Germanic mind with the romance and magic of the high Alps, and the symbol, to this day, of Germany's mountain troops—whereas the tactical emblem of the 4th was an E n z i a n (probably the Snow Gentian, Gentiana nivalis).

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

But it wasn't all flowers: After a long and arduous journey south to the mountains along dusty roads and under the blazing summer sun, down from a distant crossing they had forced 600km away over the Don River near Rostov, the German mountain troops needed to rest and regroup. Worse still: the 2nd Rumanian Mountain Division and three divisions of Italian Alpini were ordered to detach themselves from the Corps and head for the front around Stalingrad; a rifle battalion and a battery of mountain artillery were transferred to the 1st Panzer Army; and the 4th Air Corps, whose support the mountain troops had been firmly promised, was transferred to Italy.

From the outset, pitted as it was against the might of the Red Army and the Caucasus Mountains and the unbelievable ambition and criminal stupidity of its political and military masters back in Berlin, the German Army's 49th Mountain Corps had all the striking-power of a flea, and its pathetically small, isolated fighting units were swallowed up by the remote mountains and valleys of the Caucasus.

THE SOVIET FORCES, on the other hand, certainly seem to have started out much less well-prepared: 'Russians, Caucasians, Grusinians, Usbekians and Turkmenians... With the exception of a few newly-formed units the enemy had no genuine mountain forces... His units were mostly quickly [cobbled together, and were] of different strength, often badly trained and ill-equipped for the mountains.' See in particular Statiev's At War's Summit (ref. above) for descriptions of the truly appalling conditions in which Soviet troops were deployed and expected to fight the well-trained and equipped Germans. But despite these disadvantages, 'the Soviet soldier proved—like everywhere on the Eastern Front, also in the Caucasus—to be a stubborn opponent... without exception excellently armed.'

Although the mountain warfare skills of the Soviet infantryman deployed in the Caucasus were most likely not as developed as the Germans', what he lacked in professional ability he made up for in numbers and determination. Combined with its shorter supply lines (a vital advantage in any conflict, but perhaps particularly so in mountain warfare), the Red Army's near-inexhaustible reserves of manpower positively swamped the ant-like Gerbirgsjäger units—a crushing, vice-like disadvantage which an almost complete lack of resupply and reinforcement on the German side rapidly tightened.

Soviet forces were also increasingly able to benefit from supply drops from the air and close air support—notably provided by the dreaded ground-attack Ilyushin Il-2 "Shturmovik", against which the German mountain troops were unable to defend themselves. This was to prove a crucial advantage in the long run, for with the exception of a few Fieseler Fi-156 "Storks" (Storch, an extremely light, practically unarmed and remarkably slow two-to-three-man 'plane, mostly used to transport senior officers and fly out a handful of "lucky" casualties) the Luftwaffe was practically absent from this theatre of operations and the Russians never lost their complete domination of the skies above the Caucasus.

2. From steppe to mountains

The German 1st and 4th Mountain Divisions' advance up into the Caucasus

(a personal account of operations during the month of August 1942 up to the 5th of September)

Sowjetunion, Kaukasus.- Konvoi von Kettenfahrzeuge in Hügellandschaft; PK 666

(1942/43, German Federal Archives Bild 101I-031-2406-15)

Sowjetunion, Kaukasus.- Deutsche Gebirgsjäger im Schnee, Rast; PK 666

(22 December 1942; German Federal Archives)

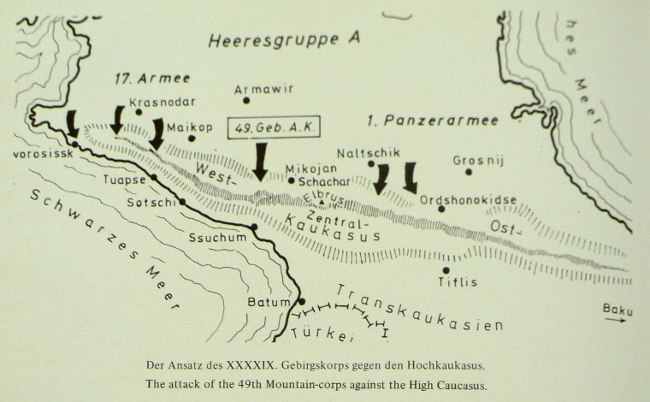

A map copied from Kaltenegger (see above):

A detailed map of the operations of Army Group A

(17th Army, 1st Panzer Army & 49th Mountain Army Corps)

between July and November 1942

(click to open a larger version in a new tab)

From the war diary (quoted in Kaltenegger, pp. 111-134; see above; my translation from the original German) of O b e r j ä g e r A l f r e d R i c h t e r, who served with the 2nd Hochgebirgs-Jäger-Batallion's headquarters staff. 'Besides the fighting at the front, this sensitive painter—whose creative work would later see him awarded a professorial chair in post-war Austria—also described the landscape and people of his surroundings as well as the simple, human concerns and needs of the average frontline soldier.'

[August 1942]

Rostov on the Don [is] completely burnt and destroyed. Now we cross the Don and advance towards Asia. We halt in the village of Kulishevka, outside Bataisk. Today's stage involves marching 90 kilometres—not much, but quite an ordeal for the drivers given the terrible state of the roads. Like most of the others, I lie down in a field and sleep.

3rd Company ["Coy"] reported two serious accidents during loading in Innsbruck [in Austria]: A cart transporting hay was burnt to a cinder when the hay, which was piled too high, came into contact with an overhead power line and caught fire. Shortly afterwards a goods train coming down from the Brenner [Pass] crashed into the transport train as it stood alongside the loading ramp, ramming into each other the first three or four flatbed cars upon which lorries had just been loaded. 1 man was instantly killed in the accident, 2 others soon died of their injuries, and 15 men, some of them with crushed legs, were evacuated to hospital. The many women who had come to bid their menfolk farewell at the station apparently also witnessed this ghastly accident.

The Batallion seems to be under a dark cloud: 4 men fell to their deaths, as it later turned out, then the other 3 and a considerable number of wounded and sick in the infirmaries. Several others also had to be left behind in Taganrog [a port city on the northern shores of the Sea of Azov]. [...]

20 August

At 05.00 we resume our march towards Kushchiovskaia. We halt at mid-day in Pavlovskaia. It is very hot. We are lucky to be able to wash ourselves with a bowlful of water. Our average speed is slow, around 20 km/h. We are unable to reach our objective and stay in Arkhangelskaia. Today we covered 191 kilometres.

21 August

We rise at 04.00 and get going again at 05.00. We pass through Kropotkin. The friendliness of the local people is surprising, who wave at us and offer us food. During a short halt I enter a farmhouse, and am immediately given tomatoes and plums. A woman hurries to fry some pancakes in oil for us. At 08.00 we cross the Kuban [River]. The bridge was apparently only relaid a week ago. The scars of fighting are still visible around us. Then we are shown proof of the vehemence of the Stuka [dive-bomber] attacks as we drive past kilometres of destroyed transport columns. The effect of the bombs upon the munitions transports must have been terrifying; [the force of the explosions was such that] sections of railway track are curled like thin wire, and in some places lie 100 metres away in fields along the railway line along with iron carriage wheels and heavy munitions. Some railway cars have melted along with their loads into shapeless lumps of metal.

The lorries need to fill up with petrol and the men immediately put the long halt to good use and go for a swim. Two hours of paradise: We race around stark naked through the water-meadows along the Kuban and swim back and forth through the river's warm, deep waters. On the opposite shore we find vegetable patches full of tomatoes, onions and herbs. Every man eats and takes what he can carry. The women at work in the surrounding fields stare dumbfounded at our naked doings. I don't know how many times I swim across the river with strings of onions and herbs around my neck and tomatoes in my hands to share these delicacies with those who cannot swim.

I have another opportunity for a swim in the evening. A thunderstorm has made driving up the sloping road impossible. We halt in [the village of] Protshnovkopskaia before [the town of] Armavir. We gorge ourselves on plums and greengages we find in an orchard on a small island in the river. We quickly organize ourselves and soon chickens, geese and even pigs are gathered. I spend the night on the 'bus. Today we covered 106 kilometres.

Interlude: the German ascent of Mt Elbruz

5,600m, 21st of August 1942

From Lucas's Alpine Elite (see above; pp. 133-134):

THE REAL ASCENT TO CONQUER THE ELBRUZ peak began on the 17th of August, and by last light of that day the group which would be making the assault had reached the point past which all portering would have to be carried out by the men themselves. Ahead lay a glacier and behind that vast sheet of perpetual ice lay the twin peaks of the mountain. Last light comes early in the mountains, and although it was only 5 in the afternoon twilight had already fallen when on the following day the men, each of them carrying between 35 and 45 kilogrammes of equipment, reached a [120-guest] hotel [built by the Soviet Union in 1936 at an altitude of 4,160m] which they named the "Elbruz Hut". There the actual assault group and the portering groups rested. An attempt was made on the 19th of August to rush the peak, but the attempt was driven back by shockingly bad weather conditions. The Elbruz was not to be taken that easily.

Like an oversized Pullman carriage, the Elbruz Hut (right) and its kitchen (left)

stand on a rocky plateau in the middle of the 800m-wide glacis of ice

of the Asau Glacier

The point group did cross the giant glacier, however, and began the final assault at mid-day on the 20th of August, but was driven back and rested in the Elbruz Hut until the following morning. At dawn on the 21st of August the assault group set out. Thick fog forced the climbers to march on compass bearings and before the journey had been half completed bad weather set in. By now it was a case of win or turn back, and the assault group forced their way forward in fog, with visibility of only a metre, and through a blinding snowstorm. By 11 in the morning the summit had been reached, the national flag raised and the divisional insignia nailed to the flagstaff. The Gebirgsjäger of the German Army stood on the highest peak of the Caucasus range.

"C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre."

22 August

We only leave at 12.30. I go for another swim in the Kuban. The thunderstorm has cooled things down. The landscape is changing; it reminds me of hilly parts of Bulgaria, only here the landscape is broader and flatter, bare and covered in steppe-grass and with table-like plateaus. Our surroundings are sparsely populated. A bad section of roads holds up our convoy for so long that today we only cover a total of 72 kilometres.

We have nicked a calf and a pig, and everyone gets a helping of goulash. Tonight I prefer to sleep in a tent rather than on the 'bus.

23 August

We press on, driving up and down endless hills. The road we are following could hardly still be described as such; it is marked as being no more than a "Panzerstraße", and was indeed probably only created by the advance of our tanks. The clayey ground is as smooth and hard as asphalt. Woe is he who tries to drive along it after it has rained! Deep, muddy pools constantly hold up the column's advance as the vehicles need to be unloaded before they can tackle them. After a long detour we rejoin the valley of the Kuban [close to the village of] Borszukovskaia. We cross the main railway line in Nevinnomiskaia. We [then] drive up the Kuban, once again along bad tracks and across country through a bleak, treeless landscape. It is still light when we reach Cherkessk and set up camp.

24 August

We are to be transported by 'bus as far as the "roads" will allow. We wait for fuel and pack our marching-bags in the meantime. Our steel helmets and the horrible gas-masks are left behind along with other superfluous equipment and clothing we have brought from Germany.

In the afternoon our transports follow the old Sukhumi Military Road into the mountains. The mountains of the Caucasus are different from the Alps: there is only one main ridge, joined at right-angles by long secondary ridges and valleys. We have barely left the plains behind and reached the first soft foothills when we encounter a different kind of people: The men have beards and wear wide-brimmed hats similar to the old traditional Tyrolean ones and dark brown sheepswool coats. Their dark faces seem hard under their low hats, but not unfriendly. Most of the women cover their heads with dark-coloured scarves tied around their necks, like the women in Rumania. The houses are primitive but proof of their owners' strong sense of order. Tiny huts cling to overhanging rock-faces like swallows' nests, their clean, lime-washed walls painted white. The geology of the Kuban River's exit from the mountains is very interesting: layers of chalk covered in clay, in other places red earth between blocks of rock æons-old. We unfortunately simply drive past all these beautiful sights, and I regret not being able to draw or photograph them. We pass through Kamennomostskii, apparently a mining-settlement. Large modern buildings stand among a multitude of small one-family houses. The place has been in German hands since the 15th of August. Our road now winds its way through a narrow, sparsely-populated valley. The road is as bad as everywhere else. We arrive at journey's end as darkness falls—the sanatorium of Teberda. The omnibuses are unloaded, and we set up camp under some birch trees in a beautiful park.

25 August

We are woken up at 05.00 by the sound of bombs exploding. A Russian 'plane has come to pay us a visit. Teberda is [a sanatorium to which people come for the clean mountain air]. The sanatorium's buildings, which resemble boxy European hospitals, are modern only in appearance and show nothing of the cleanliness which we would expect within. They are mostly filled with ill Russian children who have no intention of letting repeated aerial bombardments ruin their summer stay. These are naturally not targeted at them, the bombs being instead aimed at the headquarters of the 1st Gebirgsjäger Division (General Lanz) which have been set up here.

The maps in divisional headquarters tell me much about the results of our military operations to date: A Hochgebirgstruppe of picked men from the division under the orders of Hauptmann [Captain] Groth reportedly climbed to the summit of Mt Elbruz (5,633m) on the 21st [of August] before going into action against the enemy—a double achievement for the brave Jägers. A batallion has reportedly already crossed the Klukhor Pass and is said to be fighting on the southern side before [the settlement of] Klitsh. (I had hitherto thought this would be our responsibility.) [Our] batallion alone is currently in action against two newly-arrived Russian mountain divisions. Hard fighting has been reported. On the Russian side stand elite troops such as a regiment of officer cadets [Fahnenjunkerregiment], reportedly none of whom could be captured and who had to be killed one by one. Sharpshooters are also a dangerous adversary. An advance down the southern slopes of the Caucasus is said to still be possible but would be pointless, for German troops have been unable to push forward to the east [of our positions] or in the western Caucasus. Which makes us the tip of a southern-facing wedge. We shift our camp to another site which overlooks Teberda and is better camouflaged. But I barely have time to settle in and resume my urgent mapping duties when the Russian 'planes return. A bomb explodes close by. Once again I have to relocate my mapping station. I shelter under a thick tree so as to avoid attracting attention to myself with my light-coloured maps.

The landscape is superb, and reminds me of the Alps. The deciduous trees of the valleys give way to forests of pine higher up.

26 August

Up at 04.00. Our "work" begins. 1st Coy under Hauptmann [Captain] Schmid is to march off immediately and cross the Dombai-Ulgen Pass. We set off at 07.30 with 2nd Coy and the communications detachment ahead of us and 3rd Coy bringing up the rear, and head in a westerly direction over the Mukhin Pass (2,744m) towards [the settlement of] Krasno-Karatchai. All of us walk rather unsteadily, being out of practice on account of the long train and 'bus journeys. Our heavy back-packs make matters worse, as every man must carry four days' supplies. The Russian 'planes appear to have regular working hours. They came again in the morning and then later during our march in the afternoon. We have to take cover several times so as to avoid betraying our movements. We encounter shepherds squatting on top of boulders who probably spotted our advance ages ago. They rise rather grandly to greet us. They are fine-looking men, tall and of aristocratic bearing despite their shabby clothes. It begins to pour with rain during our final ascent. We reach the pass at 15.30. The descent [on the other side] is steep and hard on the knees. We halt, exhausted, on a rocky spur in the Marka Valley and set up camp for the night. My abdominal muscles really hurt. My colleagues from the mapping section and I are on duty tonight. Delicious-smelling coffee (40% coffee beans) improves the evening. As I am on duty tonight I cannot crawl into my sleeping-bag and am freezing, particularly my feet.

27 August

I am on guard duty from 04.00 till we leave. We wait until around 11.00 in the shepherds' camp of Krasno-Karatchai for the order to push on southwards up the Axaut Valley. We learn that two companies of the 98th Gebirgsjäger Regiment have surrounded Russian forces in the parallel valley to ours, the Marukh Valley. The Marukh Pass is reportedly held by a Russian regiment with artillery and mortar support. Our batallion is to advance towards the Pass from the east. The C.O. already indicated the locations of various Stützpunkte during the preliminary operational briefing in Teberda. These have been indicated by letters beginning with "a" on the map. 3rd Coy is to advance to Point "d" where the Malaia [small] Teberda Valley meets the Axaut Valley. Batallion H.Q. is to march to "c", 18-20 kilometres to the south of Krasno-Karatchai. The valley is amazingly beautiful. Although we have no particular heights to cross, yesterday's exhausting march makes walking sheer agony. We are happy every time we are given the opportunity to rest for a while. These halts, combined with our constant efforts to take cover and hide from Russian spotter 'planes, slow down our advance. Night has already fallen by the time we reach our positions by "c". It is raining, but we are ordered not to light fires (the enemy might spot them). Now begin my additional duties as the unit's diarist. The C.O. sends out order after order until late at night, in addition to which I have four maps to draw. Five men to a tent is already quite a squeeze, but having to draw maps by the feeble light of a little candle while sitting on the ground without being able to stretch one's legs or back is even more demanding than marching.

28 August

I leave my assistant to continue at 01.00 as I can no longer remain seated. I am woken up at 03.30, and at 4 I go with the C.O. up the valley towards Stützpunkt "d"—a collection of huts built at an altitude of 1,911 metres to serve a tungsten mine and in the midst of a beautiful forest whose trees reach high up the flanks of the neighbouring mountains. Above 1,200m the flora here in the Caucasus begins to differ from that in the Alps. This is no doubt due to the Caucasus's more southerly latitude. From "d" there is a lovely view of the valley all the way up to the Axaut Glacier and [Mt] Axaut (3,908m).

We encounter women and children in the barrack-like huts, presumably relatives of the men working in the nearby mine. I am quite surprised when one of the women walks up to me and asks me in German 'Do you by chance have a picture of St George?' She then added 'You know, I am religious, I am these children's teacher.' I am unfortunately unable to accede to her request. The women and children are sent out of the valley. In one of the buildings I find a theodolite. The women are determined to take it with them; perhaps they consider it a particularly valuable piece of equipment. We have no need for it as far as I can see, and I want to let the women keep it. But Bauer [the C.O.] orders me to hold on to it. So I curtly refuse the women their request and chase them away. My assistant and I set up the mapping station and take up our own quarters in a room in one of the huts. The C.O. takes over two rooms next to us—his bedroom and office—and the communications unit and radio operators settle in the hut opposite.

Footbridges are laid over the Axaut River's many streams.

An attack on the Marukh Pass was planned for today, but the operation is delayed until the whereabouts of the enemy's positions can be precisely established. We carry out a lot of reconnaissance today in all directions. We begin to receive reports in the evening: 3rd Coy report that they have advanced to the Axaut Glacier and that their patrols have taken up positions on some ridges, but they report no contact with enemy.

Lt Kelz from 2nd Coy reports that he and his patrol (who were advancing from "d" towards [Mt] Kara-Kaya) have succeeded after heavy fighting in taking the ridge which branches off eastwards from the main north ridge by Height 3,163[m]; the north ridge is reportedly held by the Russians, who have apparently deployed sharpshooters between the rocky outcrops of a parallel ridge.

The remaining patrols report having reached their objectives, but fear they will be unable to continue because they are running low on ammunition.

The C.O. plans to attack the north ridge of Kara-Kaya tonight and "throw" the Russians. Outlying company elements are to be grouped and deployed against Point "e" (3,080m) to the north of Kara-Kaya. Ammunition and supplies are to follow tomorrow. I am extremely busy with maps to be copied and sketches to be drawn. As I only have the use of my small box of things for sketching and drawing and the roll of maps I carry with me, the work takes me three times as long as it normally would. The entire H.Q. staff has now arrived in the Batallion's forward command post by Point "d".

29 August

Our night's sleep in the hut was ghastly; we lay on the floor, sleepless, as bed-bugs tormented us most horribly.

11.00—we have taken cover and are waiting for the Russians. H.Q. staff are to cover the withdrawal of 3rd Coy, who are still unaware of the fact that the enemy has pushed back our patrols everywhere and is threatening Point "d" down the countless streams and beds of shingle of the Axaut Valley. The feared shortage of ammunition has begun to make itself felt. The plan was too optimistic: sending a unit into combat in the high mountains without baggage and pack-animals—i.e. deprived of fresh ammunition and supplies—is a gamble. We have left the huts. The C.O. is with 3rd Coy. The result of yesterday's operations: 2 dead (Oberjäger Schenk from 2nd Coy and Jäger Veith from H.Q. staff), 5 wounded, 2 missing, and 1 Russian prisoner. In the morning comes a message reporting a further 5 dead and 7 wounded on our side, and 10 Russian prisoners.

The prisoners who were brought to us are equipped rather haphazardly and are weak with hunger. Whereas reports claimed well-equipped mountain troops were fighting on the Russian side. They wore grey uniforms, mountain boots and hats similar to ours.

The mid-day break is strangely tense. The uninterrupted sound of fighting since 04.00 up on Height 3,021, high up above a grassy slope to our west, has stopped. Have our units fired all their ammunition? The sound resumes after a while. Have the Russians been pushed back? We return to our hut and move Batallion H.Q. 300 metres back among the trees. I had just erected my tent over a hastily-dug foxhole lined with bracken to make sitting and drawing maps more comfortable when I was suddenly racked by a heavy bout of fever and a sharp pain in my back and sides. I can barely straighten myself. The C.O. has returned in the meantime. H.Q. goes back to action stations again. I am forced to remain lying in my foxhole. The C.O. comes to look for me, but is equally at a loss to explain my condition.

30 August

My fever has gone, but not the chest pains; my lower back is also painful. At least the night in the tent was more comfortable than sleeping in the nest of bed-bugs [the hut]. All the H.Q. staff spent the whole night securing the Axaut Stream, and I spent the night alone in camp. The night was calm. The Russians—who had advanced up to the stream and were calmly digging in on top of a knoll under our very eyes—were forced down from the knoll by fire from our positions and retreated into the forest on the other side of the stream. The shooting is getting closer to our camp.

Our night's rest disappears in an instant as some excitable youngster begins to shoot and throw hand-grenades in front of the huts. Every man goes to action stations. Although my fever has gone, I still find breathing painful. Two machine-gunners and I are ordered to secure a footbridge over the Axaut during the second half of the night. I am struggling not to fall asleep. The others are not finding it any easier: During my quick walk of inspection I encounter sleeping infantrymen here and there in various positions. The moon shines brightly and all is quiet except for the distant sound of fighting which floats down to us from the upper end of the stream.

31 August

More and more Russians are deserting and coming over to our lines. They say many more of them would come were not some of them afraid of their [political] commissars. They are told the Germans shoot all those who surrender to them.

I make myself some good coffee. We still have to rely upon ourselves for cooking. Although an ox was slaughtered for meat and soup, we do not have enough cooking utensils [and pots and pans] to regularly cook for the headquarters staff and our field-kitchen has still not arrived. The tinned food [we are issued with] is absolutely revolting.

I initially intended to catch up on my sleep after my coffee, but the good weather prevents this. My assistant, Herbert Pitschel, and I busy ourselves with some "housework": we dig to make our foxhole deeper and use planks to build up the sides of our tent, something which I learnt to do with the Scouts. We can now even set up a work-table in our tent. We take our work to heart and complete our new quarters by mid-day. Upon which the C.O. returns in the afternoon and orders H.Q. to relocate back into the infested huts immediately. I am seething, not so much because of the wasted effort as because of the plague of bed-bugs which awaits us. The weather changes. I notice that the weather changes much more abruptly here than it does in the Alps. The Russians withdraw. They will presumably try to cross into our valley further down from a neighbouring one.

The Russian prisoners and deserters are gathered close to us by Point "d". Today there are 18 prisoners and 14 deserters.

1 September

It has poured with rain all night. The men up in the [combat or observation] positions are having a really hard time. [Russian] deserters arrive soaked through and so weak with hunger that they are barely able to stand. This morning two of them fell into the stream as they tried to surrender and drowned. An event which took place yesterday showed the extent of what men are able to bear: Hauptmann [Captain] Geyer, who entered the valley at the head of his 2nd Coy a day before we arrived, had three civilians shot.

Yesterday two civilians were found hiding [among the banks of shingle] in the riverbed again. They turned out to be two of the three who had been shot. They fell into the stream with punctured lungs, hid among the rocks for a few days, and subsequently crawled out.

The prisoners and deserters all claim in unison that they were only given half a kilogramme of bread and two kilogrammes of raw meat to last them for five days, meat which they were reduced to eating raw because they were forbidden to light fires.

In the evening 2nd Coy takes Point "e" (3,080m) and the ridge to its north and south (which the Jägers have nick-named "the Red Wall")—an important position for the further advance towards the Marukh Glacier and the Pass. The company captured machine-guns, mortars, rifles, machine-pistols, hand-grenades and ammunition as well as 26 prisoners and 5 deserters. 2nd Coy reports that the enemy is retreating everywhere.

2 September

I slept on my work-table, a roughly-assembled surface made of three planks. To some extent this did indeed enable me to escape from the bed-bugs, particularly close to the walls. The weather is clearing. A peaceful day without fighting. The Kan-Kaya Valley is cleared of stragglers. 150 prisoners are brought to Batallion H.Q. They are locked into an old barn, whose door made of planks is locked by a simple wooden peg. We are barely able to care for them as we are not being resupplied ourselves and our reserves are running low. All we can offer them is a thin soup made of beans. They throw themselves at empty tins to lick out the last scraps of food, and cook what is left of their own meagre combat rations over little fires which they light all around our positions. They are to be used as porters. A patrol under Leutnant Dingler and 4th Coy's Alpingruppe [probably 4th Coy's specialized high-altitude detachment] advances up the Axaut Valley and take up positions in a gap in the ridge we have named the Kara-Kaya Gap (I 103). From there a flanking attack on the Marukh Pass can be attempted.

The stream has really swollen with yesterday's heavy rain and has swept away the footbridges. The prisoners are put to work replacing them. In the evening I pull a drowned man in civilian clothes out of the stream with the help of some of the Russians working in the riverbed and we bury him in a bank of shingle. I do this because I have discovered that the "spring" close to our camp from which we drink and fetch water is not a spring at all—rather a small branch of the main stream which flows under some rocks.

3 September

A quiet day like yesterday. The weather has improved slightly. My people and I are kept frantically busy with maps to be traced and reports and orders to be drawn up.

Because the Batallion is independent, that is to say not part of a regiment, it comes under direct divisional authority. Division [H.Q.] issues all our orders and instructions, and we send them all our messages and reports. Radio communications are severely disrupted by the mountainous terrain, so messengers also cover the long distance to Division H.Q. in Teberda over the Mukhin Pass on foot. It takes them two days to go there and come back—hardly a convenient solution when the message is urgent. The Batallion is therefore not only "independent" in terms of unit hierarchy: up here it is forced to rely solely upon itself. The C.O. is constantly on the move in order to keep himself informed of and involved in every development as quickly as possible. We are still cut off from our rear areas; no post or radio communications reach us.

During a pre-operational briefing the C.O. outlines his plan to attack the eastern flank of the Marukh Pass from the Kara-Kaya Gap (I 103). He asks that I be present during the briefing in order to clear up any potential confusion over the names of gaps, ridges and other geographical points. The company, patrol and combat commanders have to rely upon the completely useless 1:200,000 maps and have resorted in their reports to using names of their own for various points. We now issue them with the basic maps which I drew from our only copy of the excellent Russian 1:42,000 map—war booty which the C.O. is always reluctant to part with—and upon which I have indicated all the [necessary operational points].

4 September

A beautiful morning but unfortunately another rainy day. The C.O. climbs up to the Kara-Kaya Gap along with some elements of H.Q. and 2nd, 3rd and 4th Coys' Alpinzügen [high-altitude detachments]. The Batallion's Second-in-command, Oberleutnant Jakoby, and I must remain in the Batallion's command post.

[The body of] Leutnant Schindler from 2nd Coy, who was shot in the heart on the 30th of August, is brought down.

We are still living off nothing else but Russian tins of food which we found along with some flour in one of the huts. The tins mostly contain beans, which are covered up to a third in beef fat; very filling, but very hard to digest if one is unable to move around a lot. I think the tins of beef have given me diarrhoea.

5 September

The operation to storm the Marukh Pass began at midnight. Down here in "d" we are given a running commentary of operations as units take up their positions and begin to attack the pass: 3rd and 4th Coys' combat groups crossed the ridge by J 103 at midnight and are advancing upon J 120, 121 and 112. The first two points are taken during the morning. Possession of J 112 would deny the enemy the ability to resupply or reinforce his positions atop the pass, and a column-strong attack succeeds in throwing back the enemy and seizing the point. At 14.20 a message comes in reporting that Jägers from 4th Coy have managed to fight their way to within 50 metres of the pass. Enemy forces atop the pass have dug in. Another report quickly comes in: Marukh Pass taken by storm; 400 to 500 prisoners, only 10 to 20 Russians managed to escape; 60 to 80 Russians killed; own losses slight, for the time being confirmed to be Lt Pilarczyk and 1 man dead and 3 wounded, among them a sergeant with severe injuries.

3. Over the main ridge

The Germans capture the passes

In detail

The capture of the Marukh Pass

(2,746m; VI-IX)

September 1942

A satellite view of the Marukh Pass, taken by German mountain troops in September 1942,

a mere 50km north ("as the crow flies") of the town of Sukhumi on the Black Sea

According to Roland Kaltenegger—the author of the excellent and very comprehensive (and full of fascinating maps) Gebirgsjäger im Kaukasus: Die Operation "Edelweiß" 1942/43 (Graz: Leopold Stocker Verlag, 1997)—the capture by German mountain troops in September 1942 of the Marukh Pass, which stands 2,746 metres high close to the upper end of the Kodori Gorge, is a classic example of a high-altitude battle in mountain warfare. Its account is in any case no doubt typical of most of the high-alpine fighting which took place in the Caucasus mountains during the Second World War.

In recognition of this, Kaltenegger reproduces the official account [my translation] of the German capture (by 1st Batallion/98th Gebirgsjäger Regiment under Major Bader) of the pass; this account, a rewritten version of the original military report (which is no doubt a lot less literary and much more matter-of-fact), was embellished by Ewald Sotke—a "soldier-editor" serving in the German Army's 666th Propaganda-Kompanie, which was attached to 17th Army from 1942 to 1945.

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

Prop.-Komp. (mot) 666

Sdf. (Z). Ewald Sotke

Maruschkoj-Paß (2,756m)

8. IX. 42.

Radio report

WE ARE NOW UP ON THE PASS. We have set up camp between the rocks on either side of the saddle. Forward emplacements and reconnaissance patrols are securing the pass on the side facing the enemy. We are still aglow with the resounding victory of three days ago. It was a day just like today, brilliant with sunshine. A sky as blue as in fairy-tales was stretched over the peaks, glaciers and rocky pinnacles which surround the Marukh Pass in the wilderness of the Caucasus mountains.

In this world of high peaks and ranges whose beauty would bewitch any keen mountaineer, a 12-hour battle took place which ranks as a classic example of high-altitude combat—a battle which ended with the capture of one of the most important crossing-points in the western Caucasus and the total defeat of the enemy.

Intelligence and reconnaissance had enabled possible routes up to the pass and enemy positions to be worked out and mapped days beforehand. The pass, which runs from north to south, crosses the main range of the Caucasus, which here stretches from the north-west in a south-easterly direction. A frontal assault from the north up out of the Marukh Valley and over the northern Marukh Glacier was impossible. The heights around the pass are steep and incredibly rugged, and the crumbling cliffs of primeval rock afforded the enemy the best defensive position imaginable. Nature herself seemed to have erected this unassailable bastion to protect herself from any danger of attack. The Bolsheviks, superior to us in both weapons and ammunition, had established themselves here in strength. They had set up firing positions behind every rock and boulder, and their numerous snipers covered every angle of the valley which lay before them.

A hump-shaped ridge—jagged towers of rock interspersed with smaller notches—rises from the pass in a south-easterly direction, reaching up to peaks almost 4,000 metres high. Another ridge, running parallel to the first, towers to the south-west, and a gigantic depression filled with the southern Marukh Glacier separates the two. From an altitude of almost 3,500 metres this wide glacier, broken into enormous sections by deep crevices, flows down through the gap between the two mountain ridges, slowly transporting its moraines past the southern edge of the pass.

A plan was prepared for assaulting the pass: a frontal attack from the north by a battalion of Gebirgsjäger. The enemy had prepared himself for exactly such an assault. But: Some distance away, another battalion of specially-trained, high-altitude Gebirgsjäger was to climb the 3,488-metre-high rock-face to the south-east of the pass and to attack its southern and south-eastern flanks across the glacier and another line of rocky peaks and ridges—firing right into the Russian rear. Only when this flanking assault was rolling would 1st Batallion launch their frontal assault. The Bolsheviks had not planned for this. And when we now look from the pass to the south-east, up the course of the long glacier, its broken sections reaching up to the 3,488-metre-high wall of rock; when we gaze upon the stacked rock-faces, towers and ridges which rise on both sides of the glacier, then even we think it hardly imaginable that a heavily-armed group of soldiers was ever able to cross such obstacles and attack. But we crossed them nonetheless.

During the days and nights which preceded the assault snowstorms danced across the slopes upon which, after an exhausting climb, the Gebirgsjäger units stood in readiness in snow-caves or in tents pegged into the bare ice. Nature seemed to have allied herself with the Bolsheviks. On the last day before the attack—a day of thick fog and stormy weather—a reconnaissance unit climbed down the steep slope towards the enemy. They then crossed the glacier and climbed the last ridge but one to the south-east of the pass, which they found unguarded. This piece of intelligence, which arrived in the command post high up on the original, opposite ridge during the night before the attack, was decisive. Now an entire company could join the reconnaissance unit on their mountain-top under cover of darkness. Their machine-guns, in position and at the ready, opened fire in the cold, grey light of morning and caught the Bolshevik positions atop the last ridge before the pass in their crossed arcs of fire. Now under covering fire, a small group of men climbed down the slope facing the enemy. These men then laboriously climbed their way over the rocky, razor-sharp ridge until they reached the enemy positions atop it. Bolshevik bullets ripped through the air above the protective parapets which the men rapidly erected out of chunks of rock. The unit's leader threw 5 hand-grenades in rapid succession up at an enemy position and proceeded to take it by storm single-handedly, killing those Bolsheviks who were still alive with his machine-pistol. The rest of the unit followed him and, making skilfull use of every boulder for cover, climbed up to the two remaining enemy positions atop the ridge and destroyed them with hand-grenades and machine-pistols. 16 Bolsheviks surrendered. The summit overlooking the pass was ours. The company took up new positions atop it and began to fire upon the enemy occupying the pass itself.

At the same time as this company attacked the enemy's south-eastern flank, a heavy machine-gun crew and some riflemen, now under enemy fire themselves, moved down the glacier below the ridge to reach positions among the rocks to the south of the pass. This descent demanded the supreme effort and all the mountaineering know-how of every Jäger. They would have to climb blocks of ice 40 to 60 metres high which had broken off from the glacier in order to reach the positions they had been ordered to take up. Despite their enormous heavy machine-guns, hefty boxes of ammunition, cumbersome back-packs and unwieldy personal weapons, the usual safety of ropes and climbing equipment had to be dispensed with during the difficult climb up these vertical walls of ice. Several Jägers lost their grip or footing and fell, but they could still fight if their injuries were light. One poor Jäger died falling into a bottomless crevice of shimmering, blue-green ice which became his grave. —Having reached the top, the column found the positions the Bolsheviks were occupying, cleared them of the enemy, brought the Bolshevik resupply and approach path under fire, and repulsed several counter-attacks. During the entire battle this unit prevented any reinforcements from coming up, destroyed supply columns of porters and pack-animals on their way up to the pass, and cut off the Bolshevik positions atop the pass itself. Once the summit of the ridge was taken and the fire of our weapons spread panic and confusion among the Bolsheviks, the other Batallion began its frontal assault. It had carefully advanced towards the pass during the night until it was a mere 800 metres away. Climbing—the sharp edges of the stones tearing into their hands—an assault team of engineers [Pionierstoßgruppe] made its way up the fortress-like rock-face, sneaked through in-between the enemy's forward positions, and suddenly attacked their main, central position. The enemy was destroyed behind his own machine-guns. Now other groups were able to advance and break through. The Batallion Commander, seeing that the troops on point ahead of him were beginning to come under sniper fire, availed himself of an abandoned enemy machine-gun and poured the Bolshevik's own ammunition back at them.

The battle was soon over. The company stormed down from the flanking heights, and the frontal assault steamrolled the enemy positions atop the pass's saddle. With a loud "Hurrah!", exhilarated by how close they were to victory, the Jägers moved in to clear the enemy positions at close quarters; those of the Bolsheviks who tried to escape were cut down by our machine-guns to the south of the pass.

Most of the Bolshevik prisoners, dead and wounded confirmed what the reconnaissance unit had reported back: The Pass was defended by two well-equipped regiments. They were elite troops, among them 100 military cadets. Both regiments were destroyed. Victory had come at an incredibly low cost to our forces, our losses being barely 5% of the enemy's. The masterful way in which the operation had been prepared and was carried out paved the way for our triumph. Thanks to their intimate knowledge of rock and ice, their advance as silent as hunters, their constant manoeuvring, the surprise they achieved, thanks to their bold and ruthless attack, despite the pain and suffering they underwent during their 1,000-kilometre approach march, not to mention the effort over the past few weeks of fighting and moving at altitudes of more than 3,000 metres, the Gebirgsjäger were victorious.

New, and until now unique, however, was the performance of the High-mountain Batallion. Its commander—a renowned rock-climber from Munich who had already led 5 expeditions in the Himalayas—led the whole Batallion with all its weapons over glaciers and mountain ridges to attack the enemy flank. This massed deployment of an entire mountain Batallion, climbing its way up some of the most difficult rock-faces on earth, is new in the history of warfare. Until now, and even during the First World War, such operations had only been carried out by the smallest of units. This attack speaks of sheer boldness; that it was successful is proof of the Batallion's extraordinary levels of instruction and training. Led by world-class mountaineers, the mostly young Gebirgsjäger have proved that they have earned the right to bear the proud title Hochgebirgs-Bataillon.

4. Struggling down the southern slopes towards stalemate

and withdrawal in the face of the might of the Red Army during the fateful winter of 1942

(a personal account of operations between the 5th of September 1942 and the 9th of October)

The capture of various passes in the western Caucasus during the months of August and September marked the high-point of the 1st and 4th Mountain Divisions' advance towards their ultimate goal, Sokhumi and from there Gudauta and Tuapse on the Black Sea, whose waters shimmered tantalisingly on the horizon. So near, and yet so far.

Now, as the German Gebirgsjäger fought their way down from their newly-acquired high mountain fastnesses through the heavily-wooded southern slopes which separated them from the balmy beaches of the Black Sea, their progress ground to a bloody halt in a sea of mud and never-ending Red Army reinforcements. With "General Winter", that eternal ally of Russia, approaching fast, and weakened by months of ceaseless fighting, decimated by irreplaceable losses and virtually deprived of any kind of resupply or reinforcement, the Germans faltered.

The situation in Stalingrad and the impending doom which threatened Paulus's 6th Army (and indeed Army Group B as a whole) also cast its long shadow right over the main Caucasus range, enveloping the men of the 1st and 4th Mountain Divisions in a growing sense of gloom and desperation.

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

The men of the 1st "Edelweiß" Division fought (from East to West) in the area around Elbruz, around the upper reaches of the Kodori Gorge (of subsequent notorious fame) and around Mt Kara-Kaya and the Marukh Pass towards the upper reaches of the Adange River. The men of the 4th "Enzian" around the upper reaches of the Bzyb Valley towards the final passes barely a few kilometres from Sokhumi and Gudauta on the Black Sea coast, and close to the upper reaches of the Malaia ["Little"] Laba Valley.

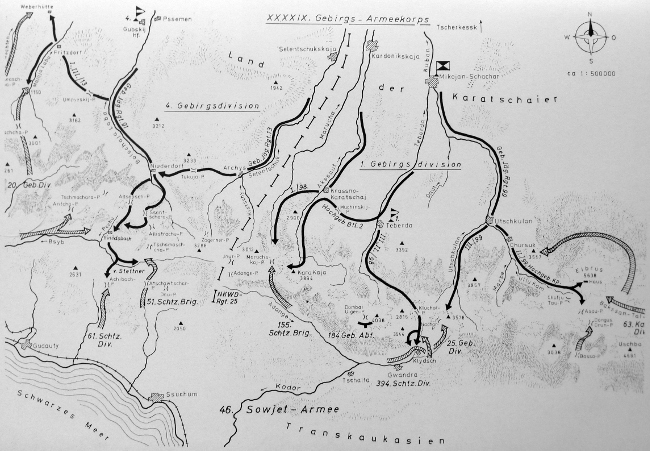

Two maps from Buchner's Der Bergkrieg im Kaukasus (see above):

A map of the German 1st ("Edelweiß") and 4th ("Enzian") Mountain Divisions' advance

into the Caucasus mountains in 1942

(click to open a larger version in a new tab)

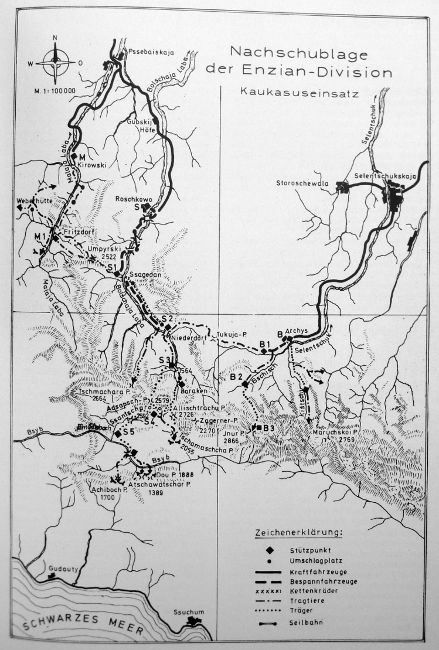

A detailed map of the German 4th ("Enzian") Mountain Division's supply columns in 1942

Note the furthest point of advance towards Sukhum on the Black Sea ("Achiboch P.")

(click to open a larger version in a new tab)

|

* |

* |

* |

|---|

From the war diary (quoted in Kaltenegger, pp. 111-134; see above; my translation from the original German) of O b e r j ä g e r A l f r e d R i c h t e r, who served as "maps officer" with the headquarters staff of the 1st ("Edelweiß") Mountain Division's 2nd Hochgebirgs-Jäger-Batallion.

Kaltenegger: 'Besides the fighting at the front, this sensitive painter—whose creative work would later see him awarded a professorial chair in post-war Austria—also described the landscape and people of his surroundings as well as the simple, human concerns and needs of the average frontline soldier.'

5 September

Immediately after the capture of the [Marukh] pass, the company's combat units take up defensive positions; on our right wing (to the west) is the Bader Batallion of the 98th Gebirgsjäger Regiment [the batallion which captured the pass; see above].

Beautiful weather crowns the day's successful operation and is a boon to all the men. The nights are already becoming bitterly cold. Down by the stream where we have our positions, fog and frost.

Our field-kitchen arrives in the evening, having taken 5 days to cover the [short but difficult] distance from Gretsheskoye to Point "d".

6 September

Calm everywhere. The good weather continues. I would love to climb up to the pass, but we must stay and work in the H.Q. I would also like to do a bit of drawing; among the prisoners we captured are some interesting faces. All of those who are even remotely able to walk have been pressed into service as porters; those who are left are more dead than alive. So I have been unable to devote myself to drawing for lack of time, but also because the prisoners I would like to portray are not always available.

Oberjäger Spindler from H.Q. climbs up to the so-called "red" ridge (by Point "e") to bury Jäger Karl Veith, his comrade, who fell on the 28th of August. In doing so, he discovers that Veith accidentally shot himself in the upper thigh, fell down on the enemy side of the ridge, was later discovered by the Russians and was killed by several gunshots, knife-stabs and blows to the head.

We receive a message informing us that 3 Russian paratroopers have landed in our divison's area to carry out reconnaissance and sabotage.

7 September

Russian 'planes come to have a look; they cannot fail to notice that Germans are occupying the pass.

Oberjäger Zöttl from H.Q., one of our mountain leaders, fell 80 metres to his death yesterday during a reconnaissance patrol in an apparently "safe" spot. A chunk of rock he was holding onto came loose and he was mortally wounded to the head.

More and more people from H.Q. find the opportunity to climb up to the pass; only we from the cartographic and communications desk must remain at our posts. Although we have nothing to do from time to time and are occasionally bored, I find the time to rest and get on with my own work. A report comes in, informing us that a reconnaissance unit from 3rd Company has advanced 1.5 kilometres to the south of Point "m" [the Marukh Pass; 2,769m] via Point "n" (1,825m) without encountering the enemy. A wounded Russian soldier they came across told them that 6,000 fresh reinforcements have just arrived in the next village.

As from tomorrow the area around the Jalovtshat Glacier and the Alubek Pass is also to be cleared, as the Russians might try to attack our rear from that quarter.

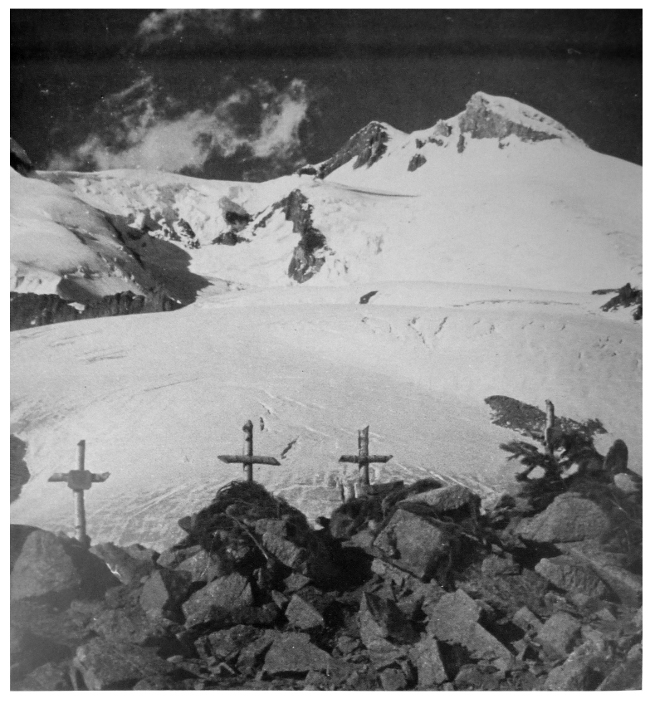

We bury near Point "d" a very young Jäger who died from a rockfall as he was being transported down following a serious injury to one of his kidneys. His grave, close by the small group of huts, is particularly shallow, as the stony ground is full of rocks and tree-roots. One of his arms, which was raised when we carried his body, remains pointing upwards as we lie him down and begin to cover him with earth, as if he were saying 'friends, stay with me, don't leave me here on my own!' I will never forget the sight of him. [...]

8 September

At 13.30 a report comes in, informing H.Q. that Oberjäger Schmid and a reconnaissance unit from 3rd Coy have spotted 2 enemy companies approaching Point "n" and that they [the Germans] are taking up positions. At 14.00 a further report: 'enemy attacking'. 3rd Coy, to the south of the pass, fights off the assault. 4th Coy and the forward Batallion H.Q. are up on the pass.

9 September

Bad weather. It has snowed up on the mountains, and the men are freezing in their positions. The first cases of frostbitten feet are brought in. At 5.00 the enemy advances again; he attacks at 8.45, but is unable to push back the fighting positions of 3rd Coy despite committing both his companies during the battle.

The forward positions bring in 11 prisoners and hold their ground until nightfall. They are then pulled back to positions J 114, 125 and 126 along the Main Combat Line [Hauptkampflinie (HKL)].

Lieutenant Kelz leads a reconnaissance patrol out from Porter-station [Trägerstation] J 102, which was established on the Axaut Glacier for the storming of the "m" [Marukh] Pass by Point 2,654, against J 105 and 106 along the main ridge west of the Axaut.

Nothing much happens in "d". Lieutenant Winsauer's main responsibility is to direct supply columns to the forward positions, a difficult task involving marches of up to 9 hours. Captured horses are loaded with needed supplies and sent up to the positions, but to little effect. Cases of bowel disease are on the increase among the men, from harmless cases of diarrhoea to full-blown infections.

The first two bags of post arrive in the evening. Nothing for me.

10 September

A terrible night's sleep because of a renewed assault by the bed-bugs. They had pretty much let me be over the past few days.

Only limited reports of fighting from the HKL. The commanding officer [(C.O.)] returns from the mountains in the evening. That means night-work for us. The engineers attached to our Batallion have built a 95-metre bridge over the Axaut River by Point "c". Rain showers during the night.

11 September

The C.O. leaves for Divisional H.Q.

A report comes in from Point "m": A Russian attack upon the HKL towards the middle of 3rd Coy's positions has been repelled.

Although it rains every day and powerful thunderstorms are frequent, we are still not in a bad stretch of weather.

12 September

A report from the pass: 'At 4.45 the enemy, 70-80-strong like yesterday, attacked 3rd Coy's right flank, and then the left with around 30 men. Oberfeldwebel Hummel and Jäger Leisinger were killed in action. The enemy lost 48 men—among them 2 officers, 1 [political] commissar and 33 prisoners; he is deploying picked and well-armed mountaineers, but is still unable to break through.'

In the morning a Russian reconnaissance 'plane arrives, soon followed by 3 bombers who drop their bombs from a great height without doing any damage.

I have eaten canned meat again, despite my aversion to it; now have diarrhoea and terrible stomach cramps.

13 September

A bit of a walk will hopefully cure my indigestion. The weather is gorgeous this morning. I walk all the way up to the north-eastern glacier of Kara-Kaya by Point "e". Dead Russians lie on the rarely-used slope. They seem to have died of exhaustion while acting as porters, not in combat, or were perhaps summarily shot by one of our supply columns for refusing to continue—a possibility which I consider because I have heard of such things happening, and because the C.O. issued strict orders forbidding the execution of prisoners.

Russian reconnaissance 'planes return, but no bombers.

3rd Coy reports that enemy forward units advanced to within 500 metres of the HKL and brought heavy mortars into action. Today our losses amount to 3 dead and 4 wounded.

The Batallion's losses during the 17 days it has been in action amount to 25 dead, 42 wounded, 33 ill and 2 missing—a total of 102 casualties, so around 10% of its total strength.

14 September

2nd Coy, which occupied positions by the newly-established "l" support point [Stützpunkt] at the foot of the northerly Marukh Glacier, rotates with 4th Coy up on the pass. The detachment of engineers leaves Point "d" and descends into the Marukh Valley to begin building [log cabins for the winter]. The forward Batallion H.Q. at "m" is pulled back to "d", to the men's relief, but no doubt mainly for reasons of economy, for every crust of bread and every bullet takes two days and valuable men and pack-animals to be brought up to "m" from "d".

[Supply] Column II has now also arrived in Mikhoyan-Shahar; 80 of their pack-animals have been allocated to our unit. Our rate of resupply is now expected to increase. The use of Karatchais [a "Circassian" people of the north-western Caucasus] with their ox-carts has, up until now, not only proven to be painfully slow but also quite unreliable, for the notion of time seems to be very flexible in Russia and some stretches of the road up through the Axaut Valley are so bad that they can barely be described as a "road". The sheer length of this road has reduced the efforts of the pioneer units to no more than a drop of water upon a hot stone. And so instead of the long-awaited resupply, reports sometimes come in informing us that a vehicle has fallen into the river and that priceless luxuries such as our chocolate and coffee have quite literally been washed away.

15 September

A column of pack-animals leaves "d" early with supplies and heads up to the pass. A report comes in the afternoon, informing us that 8 animals fell to their death. The C.O. returns from Divisional H.Q. All orders are for the preparation of winter quarters. We are making ourselves pairs of trousers. The work pleases me. But, unfortunately, we have to stop when the C.O. arrives and orders begin to rain down, which we are to convey as quickly as possible.

We will probably not remain here in "d" much longer. Rumours speak of the Batallion also being ordered to secure the Kisgitsh and Inur Passes to the west of "m". That would lead to a very over-extended frontline. And for Batallion H.Q. to even try to maintain contact with these passes and resupply points would require it to be moved doqn into the valleys; for between the valley-heads, like here in "d", the crossing places are too high and too distant, and probably very difficult to negotiate in winter. Communications are too prone to interruptions at such heights, as the steep mountain slopes render radio contact difficult.

16 September

Cold fog in the morning. We have finished our trousers. As we fold our working table away I catch 102 bed-bugs hiding in two of its [wooden] joints! The last time I washed my clothes was in the Sea of Azov a month ago. So it is slowly time to have another wash-day. I am on duty from 18.00 until the morning.

17 September

An autumn day of rare beauty. How I would love to be walking up on some mountain instead of working down here. For us, the sun disappears behind the Kara-Kaya at around 15.00, and it becomes bitterly cold.

3rd Coy reports: 00.15 contact with enemy reconnaissance unit on Coy's left flank; enemy repelled. Later enemy mortar fire on Coy's left flank. Own losses: Jg. Thomas Schmuck killed, 7 wounded.

Our art[iller]y (2./79), armed with 4 GG-36 [howitzers] below the Misti Pass close to Height 2,824, fires upon the enemy positions by "n", and is reported to have hit an ammunition dump.

A reconnaissance patrol under Lt Kelz reports: 'Ridge between 2,590 and 3,070 occupied by enemy group.' This is the ridge south-west of J 105 between Knots [Knoten] 2,586 and 3,069. [...]

18 September

The spell of good weather continues. Oberst [Colonel] Le Suire, the C.O. of Gebirgsjäger-Regiment 99 under whose orders we have now been placed, pays us a visit. Russian reconnaissance 'planes visit us once again. German Focke-Wulfs also overfly us; they are said to be bombing enemy positions in the Adange Valley.

19 September

Pitschel and I go for a three-hour walk in the Malaia ["small", "lesser"] Teberda Valley. The path winds its way up a steep, wooded slope to a primitive installation belonging to [a] tungsten mine—presumably a collection or sorting point. The mineral-rich rock was presumably mined high up on the steep mountain flanks at the end of the valley and transported to this installation. A supply railway was certainly not used, for no trace of one is to be seen. We continue down into the valley, but do not venture as far as the end. I would love to settle here for a while and paint the view of Kara-Kaya, but cannot do more than take a few pictures.

A report says Russian 'planes have been spotted air-dropping supplies to their troops on the Russian [southern] side—a sign that the Russians are finding the resupply of their troops no less problematic than we are.

Russian 'planes drop bombs and leaflets by "c".

20 September

Next to my daily work I have been busy preparing a copy of the Russian 1:42,000 map. Doing so is particularly difficult, despite the fact that I am only plotting the courses of rivers and glaciers and the positions of the most important ridges and peaks and contour lines. The indispensable calculation of altitudes in metres is no less time-consuming.

In the afternoon 5 enemy 'planes drop bombs close to the supply dump by support point [Stützpunkt] "c". No damage is sustained, but a man on a cart who failed to take cover is severely wounded by shrapnel in the upper leg.

21 September

Enemy paratroopers are said to have been dropped somewhere in our rear. 3rd Coy reports no incidents from its positions along the HKL. Our artillery continues to bombard enemy positions by "n".

22 September

3rd Coy reports no incidents from its frontline positions for the third day running.

23 September

Wonderful autumn weather. I am seated in front of my copy of the Russian map; I had underestimated the work this would require, but perhaps it will be worth all the trouble.

3rd Coy reports exchanges of machine-gun and rifle fire with the enemy. The company also reports having sent a reconnaissance unit to establish a perfect observation post on J 129 from which the enemy positions by "n" can be monitored.

The C.O. has been working hard again for the past few days to improve our resupply and to set up a support point in Archis for 4th Coy's new area of operations.

24 September

3rd Coy reports having repelled an enemy patrol on their left flank; their reconnaissance unit on top of J 129 also reports having observed in the enemy positions by "n" around 30 men in mountain gear wearing knee breeches, light-coloured stockings, grey-green or light-brown blouses and light-coloured woollen caps, without coats but with fully-loaded backpacks, and believes they could be English.

The C.O. returns from Archis. 4th Coy are reported to have sent two patrols towards the Inur Pass yesterday. It has become relatively obvious that the Batallion will spend the winter in its area of operations. H.Q. is apparently soon going to move to Archis.

The Russian 'planes come every day, but without dropping bombs.

In the evening a message comes in from J 105, reporting that the ridge running south-west from height 3,069 has been occupied by a company of enemy troops. The C.O. immediately forms a column from the men deployed around "m" and send it to reinforce the reconnaissance patrol up on J 105. He leads the column himself. Oberleutnant Jakoby and myself join them at the last minute. Bauer [the C.O., Major Bauer] tells me to bring up the rear and firmly orders me to make sure everyone keeps up with the column—by force if necessary.

25 September